In Brief – Roman London

London was founded by the Romans at the point where they could easily construct a bridge over the River Thames. The earliest settlement lasted only a few years but thereafter grew into a major town and the capital of the Roman province of Britannia.

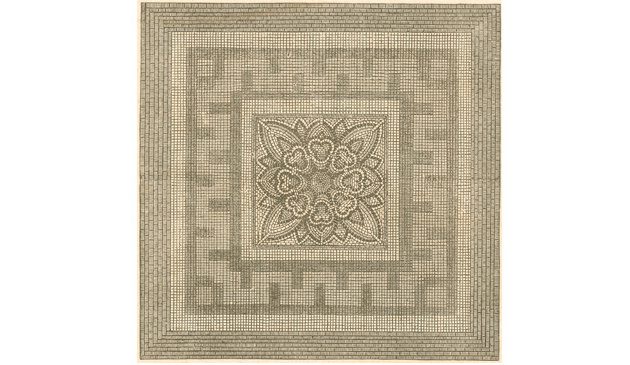

A 1st or 2nd century mosaic featuring the Roman god Bacchus, found during construction work in Leadenhall Street in 1803

© The Trustees of the British Museum.

The first Roman invasions of Britain were by Julius Caesar in 55BC and 54BC, but they were short-lived. Thereafter the expansion of the empire under Caesar’s military leadership, north to the Rhine and west to the Atlantic coast of Gaul, became legendary. As time went on the Roman aristocracy longed for new glories and the overthrow of British barbarians seemed an easy solution. The pretext presented itself in the form of restoring the exiled and compliant British tribal leader Vericus, who had been forced out of his kingdom in what is now Sussex. In 43AD, during the time of Emperor Claudius, an invasion force led by the general Plautius crossed the sea from Gaul. This time the Romans stayed and for almost four hundred years England became the most north-western part of the Roman Empire.

As they headed north, Plautius and his army pursued and then fought the local tribes. They soon arrived at the wide river Caesar had first recorded as ‘Thamesis’. Prior to the invasion the river was the border between different warring tribes. The area, with its poor clay soil, remained forested and largely unpopulated, being far from each of the tribes’ main settlements and therefore too difficult to defend. It was wider than today, flowing around sand banks and islands and fed by many small streams, its edges marshy and tree-lined. The wide river and thick forests on each bank made it a natural barrier between the different groups of people but also an easier means of transport and trade than overland.

Having succeeded in their initial mission of subduing the local tribes, the invaders needed to maintain a land supply route back to Rome via Gaul, so the temporary pontoon bridge military engineers had erected over the Thames stayed and was rebuilt. Such a strategic site needed a staff to protect and maintain it and a settlement grew, becoming both a small port and the hub of the supply routes in the new Roman province. Four years after their arrival the Romans formally decided to build a town to be known as Londinium.

In 60AD the native Iceni tribe in the northern half of East Anglia rebelled against the Romans. Led by the late king’s daughter Queen Boudicca, they rose up and, joining with others, destroyed the Roman provincial capital of Colchester. The main Roman army in Britannia was then fighting in Anglesey. They marched south as fast as they could but did not have sufficient strength to take on Boudicca’s army. The rebels burnt Londinium to the ground, killing its entire population, and then moved on to St. Albans, which was also destroyed. The rebellion was finally quashed by the Roman forces during a major battle in the Midlands.

The first Londinium had lasted a mere thirteen years but the Romans set about rebuilding the town. If the province was to grow into something similar to others such as Gaul somewhere more appropriate and accessible than Colchester was required as the capital. Londinium was the obvious choice. It was a useful place to cross the Thames and from there a network of roads could spread out to other towns. The Romans began enlarging the previously modest town as a local copy of Rome, with many grand buildings to house senior officials. A vast basilica was constructed in the centre as the town hall, as well as a large complex of buildings to accommodate the administration of the province. Following the rebellion, the new Provincial Procurator based his permanent headquarters and civil service there.

Supplies arriving from the Continent for the continuing military campaigns in the distant parts of Britain were channelled through Londinium, arriving either by ship or across the bridge, and the town was kept busy and wealthy. In the early 2nd century a large stone fort was constructed just to the north-west of the built-up area, at what we now call the Barbican. It was used mainly for housing the many troops who passed through Londinium.

Around the town’s central area new structures began to cover more ground. The Emperor Hadrian visited Londinium in 122AD and many public buildings were built or rebuilt for the occasion. During his reign a large forum was erected adjoining the basilica to form the four sides of a large piazza containing an open market. A new amphitheatre, used for sport and popular entertainments, was constructed from stone and brick to replace the previous wooden version to the south east of the fort. Public baths and temples were added, and residential areas came into being. On the south side of the bridge there was a hamlet of workshops and farm buildings.

By that time thirty thousand people lived in the town: soldiers, administrators, merchants, craftsmen, artists, native British and others from different parts of the empire. Grand houses were appearing as well as other monumental buildings such as theatres and temples. The streets and buildings were adorned with statues and frescos of gods and goddesses.

From the beginning, Londinium was a town that existed for trade and its port gradually became one of the busiest in the entire empire. Initially most of the goods being imported were to supply the military campaign and the first wave of Roman occupiers. As time went on the town grew, new settlements were established around the country, and greater quantities of raw materials and domestic luxury goods were required. Workshops opened in Londinium to produce goods for the local population.

In addition to the resident population there were large numbers of troops, officials, civil servants and trades-people continually passing through Londinium and it is not difficult to imagine it as a very cosmopolitan town. The population of Britain is estimated to have been somewhere between one and two million people by the 3rd century, with at least fifty thousand, and perhaps as much as a hundred thousand, living in Londinium, a number that would not be achieved again until the 14th century.

There was no single dominant religion in the Roman empire. Various faiths co-existed together, including the worship of Greek and Roman gods, as well as pagan beliefs. There were probably various religious temples in Londinium and one was certainly for worshippers of Mithras. Christianity became prominent during the reign of Constantine in the early 4th century.

Roman civilisation reached its zenith during the mid-1st century at around the same time Londinium was being established. While the town matured and grew on the western extreme of the empire during the 2nd and 3rd centuries it was protected, and occasionally prospered, from troubles in Rome and elsewhere. In 260 the empire was over-run by Alamanni, Franks and Goths from the north, Moors from the south and Persians from the east. Only Rome, the Italian peninsula and Britain remained untouched. The Romans fought back but large areas of the empire were lost forever.

Britain was not entirely immune from attack. The Franks, based in the lower Rhineland areas, began making raids on the wealthy and vulnerable east of Britain and the Thames estuary. In the early 3rd century, about one hundred and fifty years after their arrival, the Romans replaced Londinium’s defensive mound with a wall over three kilometres long, six and a half metres high and enclosing an area of three hundred and twenty-six acres.

Londinium went into a long, slow decline during the 4th century. It had become successful partly because it was the most convenient port from which to trade with the Rhineland and near Continent. As the Roman armies lost control of the northern Continental areas, and it became safer to ship goods to and from Boulogne, the ports on the south coast of Britain became more suitable. By the end of the 4th century Winchester had overtaken Londinium as Britain’s leading commercial centre. The town’s population gradually dwindled, concentrated along the riverside. Many buildings were no longer used and earth was laid over derelict structures so that the land could be used for farming. Even into the Middle Ages half of the land within the city walls was being farmed as fields, orchards and gardens.

Barbarian attacks were becoming more threatening to Britain and the population appealed to Emperor Honorius for help. Rome itself was under immediate threat, however, from the Visigoths who briefly entered the city in 410 carrying away much of its valuable possessions. After the Visigoths had already left Rome Honorius replied to the British that he was unable to help them at that moment and authorised the people to take care of their own defences. Britain was from then on no longer a province of the great empire to which it had been part for three and a half centuries.