The East India Company

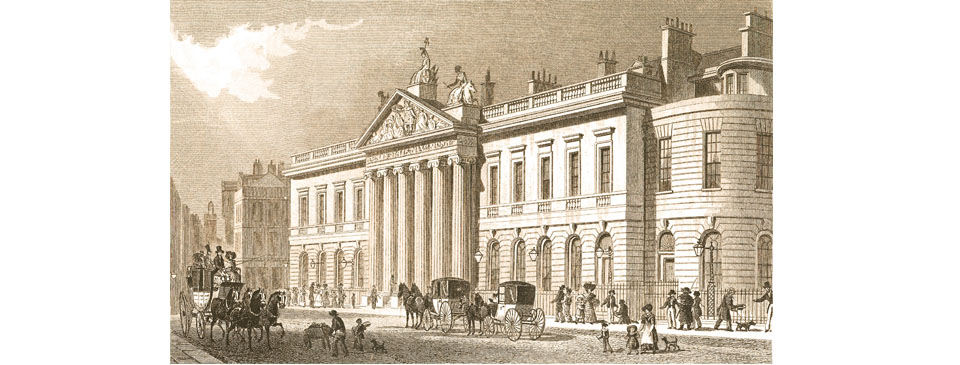

East India House in Leadenhall Street in the City of London. The Company had occupied the site since the mid-17th century but expanded several times. This building was designed by Henry Holland and work began in 1796. It included a museum housing the Company’s collection of exotic items. The building was demolished in 1862 following the Company’s demise and is now the site of the Lloyd’s insurance building. The drawing is by T.H. Shepherd and published in 1829.

In the 18th century the world’s greatest commercial business was based in London, with its grand headquarters in Leadenhall Street in the City. During its 270-year history the East India Company brought spices from the Far East that changed Britain’s cuisine, refashioned the nation’s use of fabrics from wool to cotton, then introduced tea as the favoured beverage. More significantly, it was in large part responsible for changing the world’s economy in favour of Britain but at great cost to the Indian sub-continent and China. Initially a trading company, its private army conquered a huge country, leading it to rule over a vast population.

For centuries Asia was the world’s greatest manufacturing area, with spices and exotic luxury goods sent overland from there to Europe via Istanbul and on to Venice. Thus, a camel was incorporated into the heraldic device of London’s medieval Grocers’ Company. Vasco da Gama was the first European to open a direct sea route with the Far East, first arriving in India in May 1498, and the Portuguese monopolised maritime routes with India and China for the next century, bringing valuable silks and spices to Europe.

Political conflict with Spain and Portugal in the second half of the 16th century disrupted supplies of Asian products from reaching England. A group of London merchants attempted to trade via the Baltic and Russia, forming the Muscovy Company. Another group, with overlapping membership to the Muscovy Company, went via the Mediterranean as the Levant Company. In April 1591 James Lancaster set out from Devon with three ships owned by Levant Company merchants to find a route to the Far East, reaching Ceylon (Sri Lanka). The mission was a disaster and few of the crews arrived back in England in 1594. Nevertheless, the voyage provided much useful information that would be used in the following years.

In the second half of the 16th century Spain, Portugal and the Netherlands were part of the Habsburg Empire but when the Dutch formed their own independent state in 1581 their supply of Asian products was severed. In 1595 a Dutch fleet sailed to Indonesia and thereby ended Portugal’s monopoly of trade with the Far East. That led to the formation of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) in 1602. It established a dominant position during the following century and for a time the VOC accounted for half the world’s shipping.

Political differences between the various nations disrupted imports of spices to England, which caused the price of pepper to almost triple. News of a successful voyage to Asia in 1599 by the Dutch encouraged London merchants to enter the trade. A meeting was chaired by the Mayor at Founders’ Hall and an association, dominated by Levant Company merchants, was formed. On New Year’s Eve 1600 a royal charter was granted by Queen Elizabeth to the ‘Company and Merchants trading to the East Indies’, or ‘East India Company’, giving them a monopoly on English trade between the Cape of Good Hope and Magellan’s Strait.

A small fleet of well-armed ships carrying around 500 crew, many of them Thames watermen and commanded by James Lancaster, sailed from Woolwich in 1601, backed by 218 subscribers. A variety of goods, including metals, fabrics, lace and gifts for foreign officials, as well as bullion, were sent on the outbound voyage. Despite poor sailing conditions that made for slow progress and many of the crew succumbing to scurvy, they arrived at Achin on the Indonesian island of Sumatra in the spring of 1602. A trade agreement with the sultan was struck and a small settlement established as a base. Pepper, cloves, indigo, mace and silk were brought back, providing substantial returns for the investors. Subsequent voyages were also highly successful, so on further sailings the company’s ships sought additional trading places, on the coast of India and as far as Japan.

England’s main product was woollen cloth, for which there was little interest in the warm climates, and other manufactures were of inferior quality to those produced in Asia, so the company had to mainly trade with bullion. It was therefore given the right to export silver – something that had previously been illegal – in order to purchase spices. The eighth voyage alone provided subscribers with a 221% profit. Continuing voyages ensured that spices were thereafter widely available in Britain, changing the nation’s cuisine. In 1617 alone the company brought back to London two million pounds weight of pepper. A decade later a commercial treaty was concluded with the powerful Mughal emperor, who ruled much of the sub-continent, giving the East India Company exclusive trading rights with the Surat region. By 1620 the Company had established twelve factories in the Far East.

During the early decades of the 17th century the members of the East India Company were amongst the greatest merchants of the City of London, many of whom were also aldermen. Not only was it necessary to be wealthy to finance expensive voyages but also to have a close relationship with the King and his government to negotiate duties and privileges. There was overlapping membership of the East India and Levant Companies, as well as the Muscovy Company.

The first chairman of the East India Company was Sir Thomas Smythe. He was a member of both the City of London’s Skinners and Haberdashers livery companies and succeeded his father as Collector of Customs for the Port of London. He sat as an MP, a City alderman, and served as Sheriff of London. Smythe was a member of both the Merchant Adventurers and Levant Company, making him one of the most important London merchants of the late 16th century. He was knighted in 1603 by James I, who appointed him as Ambassador to Russia. Returning to London he immersed himself in the East India Company, which for the first 20 years operated from his house in Philpot Lane. In 1606 Smythe arranged the granting of the first charter from King James for the Virginia Company, which was responsible for the settlement of Jamestown, and served as its first Governor. He served as Governor of the East India Company until 1621 except for two years.

The company’s fortunes waned during the 1630s due to competition from the Dutch and low selling prices of the products being returned to England. There was a lack of enthusiasm from investors and doubts that the company could survive. King Charles invested in, and granted a charter to, an alternative scheme to trade in those places neglected by the EIC around the Indian Ocean, led by Sir William Courteen, the founder of the colony of Barbados. A primary interest was the creation of a new colony at Madagascar. A fleet sailed in 1636 but Courteen died within three months of its departure and the Courteen Association became a very expensive failure.

Despite these issues, a fleet of four vessels was sent out in around 1642. The sinking of one of the ships led to a loss of the venture. Yet there was some success in the creation of the agreement with the local ruler to establish a fort on the east coast of India, resulting in the establishment of the town of Madras (now known as Chennai). That in turn created an important springboard for future trade with Bengal.

With the overthrow of King Charles, being loyal to the monarchy became a liability during the Civil War. The incumbent members of the company were replaced with a new breed of traders. They were men who had been involved in trade with the American and West Indian colonies and supporters of the Courteen Association, led by the London merchant Maurice Thomson. In 1657 the Cromwellian Protectorate granted the company with a new charter that merged it with the Courteen Association. Until then each of the early voyages was funded as an individual venture but a permanent joint-stock corporation was formed, allowing the shares to be publicly traded. They could initially be purchased from the East India headquarters and later at the Royal Exchange.

Thomson and his associates arranged for the company to lease the Guinea Company’s right to trade with the coast of Africa. It was useful to the EIC, who could then re-provision at Guinea Company forts on their voyage, as well as collecting gold to be used as currency in the Far East. On their return journey they could bring fabrics and cowrie shells that were in demand in Africa. Two years later an important supply base was also established on the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic, en-route between England and the Far East. An additional supply base later became available when a British colony was established at Cape Town during the Napoleonic Wars.

The Cromwellian Protectorate came to an end in 1660 with the Restoration of the Monarchy. Charles II granted the EIC with a new charter the following year, which significantly extended its powers. It was thereafter authorised to govern its own settlements, raise armed forces to protect its trade, to mint its own coins, and arrest interlopers. On the other hand, Charles replaced the Guinea Company with his own Royal Adventurers into Africa company, thus ending the East India’s short involvement on that continent.

The competition for trading bases in Asia and specific produce such as nutmeg and mace was fierce and often bloody. The Dutch VOC were better-organised, with superior fleets, and ruthless. In 1682 they finally expelled the East India Company from the Spice Islands. Instead, the English focussed their attention on India and its textiles. One of the Company’s trading stations was established at Bombay (Mumbai) on the west coast of the Indian sub-continent. It had been transferred to Charles II in 1661 as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza (as was Tangier in Morocco) by the Portuguese who had originally established the port but found it increasing difficult to defend. Bombay was rented to a reluctant East India Company in 1667 for £10 per year. In time it proved extremely beneficial and also acted as a model for subsequent colonisation. In the 1690s another base was established at the commercial centre of Calcutta on the prosperous Bengali coast of India and the area was soon providing over half the Company’s imports from Asia.

By 1700 the East India Company was making twenty to thirty sailings per year to the Far East and was England’s largest corporation. The Indian subcontinent accounted for substantially more than 20 percent of the world’s gross domestic production, compared with less than two percent by Britain. The Bengal region in the north-east was the richest part of the Mughal empire. Its weavers had for centuries efficiently produced a vast range of the finest textiles in silk and cotton. These colourful products, such as muslin, calico, chintz, dungaree and gingham, became the East India’s primary imports into England. Business boomed and in the early 18th century East India-imported calico overtook native British wool as the most popular textile in English homes. This was to the great detriment of the local weaving industry, leading in 1697 to riots by London’s textile workers and assaults on the property of the Company and its directors. Two decades later there were attacks on London’s streets on women wearing calico. The government’s response was to restrict its importation and ban the use of powered looms in Bengal.

Between 1699 and 1774 the East India Company’s business increased to as much as 15 percent of total annual imports into Britain, its taxes and other payments often keeping the British government solvent. From its headquarters in London instructions were sent around the world regarding what goods should be purchased and the price to be paid. Local Company governors in India were given autonomy as to how those purchases could be achieved.