In brief – London during the mid-19th century

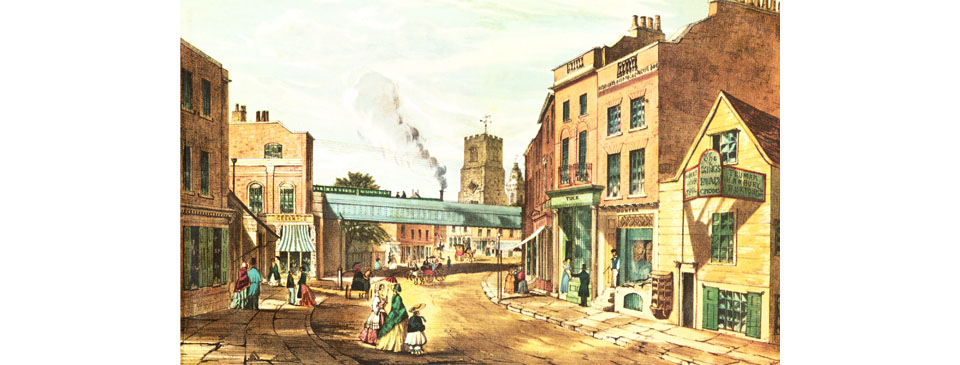

A train from Camden passes over Mare Street, Hackney on the new North London Railway in this engraving from the early 1850s. The railway was built to provide a link between the London & Birmingham Railway at Chalk Farm and the East and West India Docks. The section through Hackney was completed in 1850 and the entire line opened in January 1852.

London grew rapidly in the first half of the 19th century. Omnibuses, and then railways, allowed people to live further than walking distance from their home. The middle-classes moved out of the centre to the expanding suburbs, leaving behind them the very rich and the very poor. The writer and MP William Cobbett described London as the “metropolis of the empire” but also “the great wen” (great cyst).

George IV died in 1830 without a legitimate heir as he was pre-deceased by his brother Frederick, Duke of York. The throne therefore passed to the youngest brother, William. ‘Sailor Bill’ was by then already sixty-four years old and himself without a legitimate heir, thus ensuring his reign would be short and his heir would be a relatively distant relation. If the reign of George was a low-point in the popularity of the British monarchy, that of his brother – William IV – was the beginning of the revival that culminated in the splendour of Victoria and Edward VIII.

From 1824 William and his wife Adelaide lived at Clarence House, beside St. James’s Palace. When he ascended the throne the enlargement of Buckingham House, intended by George as a grand royal palace, was still incomplete. William anyway preferred to remain at Clarence House and discussed with the Duke of Wellington the possibility of the new palace being instead used as barracks. Once work was complete, however, Victoria was the first monarch to live at Buckingham Palace.

William’s short reign was very much one of transition from the Hanoverian period to the Victorian era and the country was evolving quickly. New innovations brought with them a great change outside London, from an almost entirely agricultural economy to one that was increasingly industrial, particularly in the coal-providing north and Midlands of England. A growing empire around the world ensured a vast market for machinery and other manufactured products.

In 1834 a furnace of the House of Lords filled with Exchequer tally sticks overheated, causing a fire. The blaze destroyed the entire Old Palace of Westminster, with the exception of the medieval Westminster Hall and Jewel Tower. A competition was held for a design for a new Houses of Parliament and from ninety-seven entries the one chosen was in the Gothic style by the architect Charles Barry. He hired Augustus Pugin to design the interior and details. The work was not completed until the 1860s, by which time both men had died.

Pious William IV followed the hedonist George IV and likewise some of his subjects, or at least those passionate in their Protestant faith, became more evangelical and moralistic. So it was that Britain entered the Victorian era, with the new monarch matching her uncle in religious zeal. Both the Church of England and the various non-conformist denominations were newly energized and, in particular, there was a Methodist revival. Evangelical preachers attracted crowds as they preached outdoors or in halls and churches, and sinners were sought out for conversion.

As London expanded, a plan was created to build new Anglican churches in the metropolitan area, much as had been unsuccessfully attempted a century earlier. This time there was much greater success, with voluntary subscriptions far exceeding expectations, and by 1856 over a hundred had been consecrated.

The centuries-old distrust of Catholics was slowly abating and, with a growing number of Irish and French Catholics in London, new churches for their worship were also being established. In 1848 a Catholic cathedral was consecrated at St. George’s Fields at Southwark, the first Catholic cathedral in Great Britain since the Reformation.