In brief – Plague and Fire

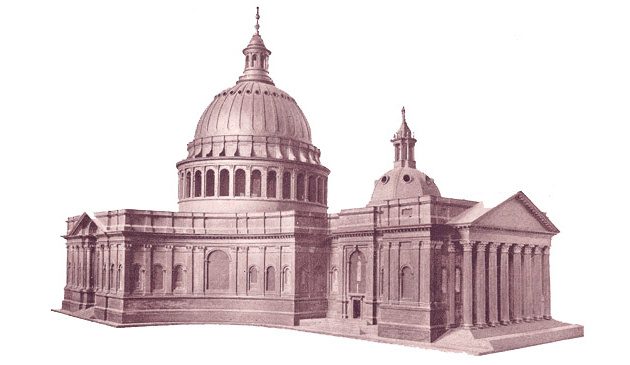

The rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the late 17th century under the direction of Sir Christopher Wren. Work began in 1673, seven years after the fire, and was to take 35 years.

London had gradually developed over hundreds of years, with little planning. Irregular-shaped buildings almost touched each other across narrow streets and alleyways. Most premises were constructed of wood, heated by open fires. There was an inefficient system of sewage and rubbish collection. It was a perfect combination for a plague and fire.

With an ever-growing population and little in the way of sewers, London was an unsanitary place. Offal was left to rot outside butchers’ premises and open drains carried human waste through the streets. In the winter months the city was wrapped in a thick fog as a result of coal fires being burnt in every house for heating and cooking. Little attention was paid to a few fatalities around the Covent Garden area in April 1665, the victims experiencing a high fever and delirium, swellings on the body and haemorrhages under the skin. In May there were seventeen such deaths reported in London and its suburbs but in June this had risen to over two hundred each week and the authorities began to take emergency action. By September over 7,000 died within a single week, the epidemic finally petering out by February of 1666. For months the city became a quiet and eerie place, with markets closed and people forced to stay within their homes as much as possible. Workshops shut because coal boats no longer arrived at the quays with the necessary fuel.

According to the contemporary Bills of Mortality sixty-eight and a half thousand people died of the Great Plague of 1665 although the actual number was probably between eighty and one hundred thousand, almost a quarter of the city’s population. In the new year of 1666 such deaths were in decline and the last reported case was at Rotherhithe in 1679. It was the last major plague of its kind to reach London.

The year following the plague, in the very early hours of Saturday 2nd September 1666, a fire began at the premises of a baker in Pudding Lane in the City. Sparks blowing in the strong wind that night spread the blaze along neighbouring wooden properties, made dry by the hot summer. The Mayor was summoned but he decided it was not serious enough to create a firebreak by demolishing adjoining houses. “Pish! A woman might piss it out” he famously exclaimed. The fire continued through the night and by eight o’clock in the morning 300 houses had been destroyed. Hour by hour it spread to warehouses along the river filled with inflammable materials and even London Bridge began to burn. The conflagration continued to spread throughout the following day, devouring ever more of the City. Homeowners and business people frantically moved whatever possessions they could carry by hand or cart.

When King Charles and his brother, the Duke of York, heard of the disaster they sent a message offering the assistance of guards from their barracks at Whitehall Palace but the Mayor still felt it was not serious enough for troops to enter the City. Having seen the disaster with his own eyes from the safety of the royal barge, Charles decided he must over-rule him and ordered the Coldstream Guards to give assistance in the firefighting.

Efforts were nevertheless haphazard and ineffective and the fire went on to spread throughout Sunday, carried onwards by the continuing strong wind. It reached Cheapside on Monday afternoon and the Royal Exchange that evening. On Tuesday evening the conflagration reached the mighty St. Paul’s Cathedral, which burned through the night. By then the Duke of York had taken command of fire-fighting efforts, with military engineers using dynamite to create firebreaks. On Tuesday night the wind died down and changed direction and the fire-fighters were finally able to bring the blaze under control.

The Great Fire had destroyed five sixths of the City, an area of 373 acres, plus a further 63 acres outside the walls. Fifteen of the City’s twenty-six wards were completely gone. Eighty-nine churches and six chapels had been damaged or completely destroyed. London had temporarily lost the Guildhall, its place of government; the Royal Exchange, its centre of commerce; St. Paul’s, its spiritual centre; and the wharves along the river through which much of the nation’s import and export trade passed. It took more than fifty years to complete the rebuilding.

Over 13,000 houses had been burned or demolished in 460 streets and over 70,000 people were left homeless. Fortunately, there was fine weather so thousands were able to camp out in fields around London at places such as Islington, Highgate and Southwark. The markets had been destroyed so the King arranged for bread and supplies to be brought in from surrounding areas.

When people were able to venture back into the City they found a landscape where it was possible to see from one side to the other, a large flattened area dominated by a few stone-built spires. The old Gothic St. Paul’s Cathedral still stood high above the chaos but was in a bad state, the brand-new portico partially collapsed. Despite such great destruction there was very little loss of life. Only a handful of deaths were reported.

Most MPs refused to accept that the fire was an accident, believing it to be the work of foreigners or Catholics, and voted for an enquiry. A committee sat for several months and were given evidence of a number of potential culprits. A young Frenchman gave extraordinary and false evidence of how he had been part of a gang that had started it. When the owner of the bakery was called by the enquiry he naturally insisted that it wasn’t his fault and that the fire at his premises must have been started deliberately. The Frenchman was found guilty and hanged at Tyburn at the end of October 1666. A commemorative plaque was fixed to the building that replaced the bakery stating: “… Hell broke loose upon this Protestant City from the malicious hearts of barbarous Papists…”.