Early Christianity in London and Westminster

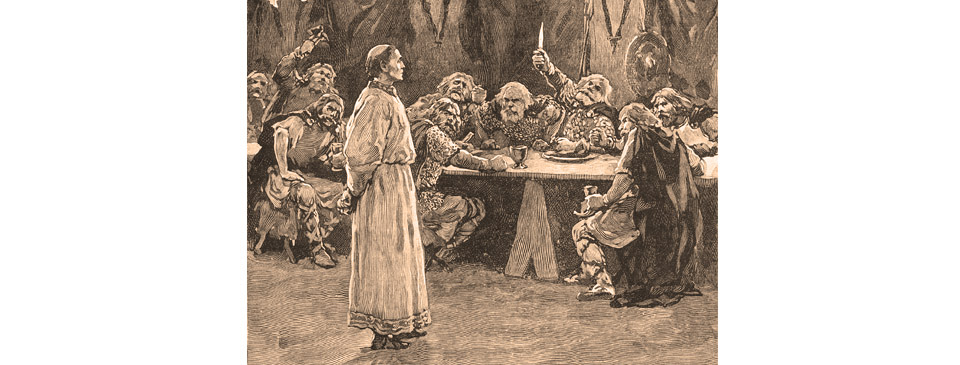

A 19th century illustration of Archbishop Alfege. The legend is that he was brought before the Danes during their Easter feast at Greenwich in 1012, after his capture following the siege of Canterbury the previous year. Refusing to pay a ransom for his release it is said that he was mortally wounded and killed by one his own followers named Thrym in order to end his pain. His remains were initially buried at St.Paul’s in London but later removed to Canterbury by King Cnut.

Christianity came to Britain during the Roman period but was not firmly established until the 9th century. St. Paul’s Cathedral and Westminster Abbey were founded during the Saxon period, as well as several churches in the City of London.

In 314AD three bishops from Britain – London, York and Lincoln – attended the first Council of Arles, a synod convened by Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor. It is unknown whether Christianity survived during the following centuries but certainly the former town-based bishoprics had disappeared sometime after the visit of Germanus, Bishop of Auxerre, in 429. The early Saxons who thereafter populated much of England in the 5th and 6th centuries were pagans.

In 596 Pope Gregory the Great sent the Benedictine Augustine and forty monks to Britain to convert the Saxons to Christianity. King Ethelbert of Kent, married to the Christian daughter of the King of the Franks, allowed them to establish a church at Canterbury and himself converted in 597. In 601 Gregory sent a second group of monks to England, including Mellitus, with instructions to establish two Christian provinces, each centred on the old Roman capitals of London and York. Augustine, as Archbishop of Canterbury, consecrated Mellitus as Bishop of the East Saxons. Aided by Ethelbert’s nephew Sabert, Mellitus set about the conversion of the people of the diocese, which covered Essex, Middlesex (including London) and part of Hertfordshire. According to the monk and historian Bede, writing in the 730s, Ethelbert founded the church of St. Paul in London – at that time a deserted city – as the episcopal seat of Bishop Mellitus.

On the deaths of Ethelbert and Sabert about 14 years after the foundation of St. Paul’s the East Saxons reverted to paganism. In 616 Mellitus and his followers were driven out by Sabert’s sons and heirs and he fled to Gaul. He returned later as Archbishop but, with London occupied by the pagan East Saxons, he based himself at Canterbury and thus the see of southern England has remained there forever more.

In the mid-7th century King Sigeberht of the East Saxons converted to Christianity. Cedd, a priest from Northumbria, was then ordained by Bishop Finan of Lindisfarne as Bishop of the East Saxons. Cedd set about founding various churches, as well as a monastery at Tilaburg (Tilbury). After Cedd returned to Northumbria the East Saxons once more returned to paganism.

Christianity was re-established around London from 675 with the appointment by Archbishop Theodore of Erkenwald as bishop, at a time when the town was under the control of King Hlothere of Kent. Who exactly Erkenwald was is not entirely clear. He certainly had influence and was probably the son of a Saxon king, with a sister by the name of Ethelburga. There is a legend that Ethelburga became a nun to avoid marriage but, more certainly, Erkenwald founded two abbeys, one at Barking and the other at Chertsey, Ethelburga became Barking’s first abbess. Erkenwald died in 693 at Barking Abbey and was buried in St. Paul’s church in London. He was later canonised and his tomb became a medieval shrine until his remains disappeared during the Reformation.

Following Erkenwald, the line of Bishops of London has remained unbroken into modern times despite London being dominated at various times by the kingdoms of Essex, Kent, Mercia and Wessex and Vikings. Fulham Palace, beside the River Thames to the west of London, has been the home of the bishops for centuries and can be dated as far back as 704 after the land had been granted to Bishop Wealdhere.

The church of St. Alban Wood Street (as well as the abbey of that name in Hertfordshire) was probably founded by King Offa of Mercia in the second half of the 8th century at a time when he dominated both the Midlands and much of Southern England.

In the mid-9th century Essex and London were under the control of the heathen Vikings. After being captured by Alfred of Wessex in around 886 London thereafter reverted to Christianity. However, Essex, to the east of the River Lea, remained within the Viking territory of Danelaw and, although the Viking leader nominally converted to Christianity, the authority of the Bishops of London is unlikely to have extended eastwards during that period.

In order to develop and control London Alfred granted areas of land in the town to his close advisors the Archbishop of Canterbury and Bishop of Worcester, as well as to the Bishop of London. Several churches were founded in the town during his reign, in addition to the already-existing St. Paul’s and All Hallow’s at Tower Hill. They included St. Gregory’s (immediately beside St. Paul’s and later incorporated into that building), St. Augustine (to the east of St. Paul’s), St. Peter ad Vincula (later incorporated into the Tower of London where it still remains), and St. Helen’s Bishopsgate. St. Martin-le-Grand, north of St. Paul’s, was founded by one of Edward the Confessor’s ministers and thereafter had strong links to the monarchy.

The most notable of the Saxon-period Bishops of London was Dunstan. A courtier and advisor to several Saxon kings, he was appointed as both Bishop of Worcester and of London from 958. Two years later he became Archbishop of Canterbury. A noted scholar, he was a strong reformer of the Church in England and canonised in 1029, about 30 years after his death. In the early medieval period he was a popular saint in England and three churches in London were dedicated to him.

In around the 960s or 970s Dunstan had established a Benedictine monastery on the small island to the west of London where the River Tyburn divided before it flowed into the Thames. King Edward (the Confessor) had an uneasy relationship with London and, when he decided to establish a grand new abbey dedicated to St. Peter, he rebuilt Dunstan’s monastery. It became known as Westminster Abbey. The work began in 1045. Such was the grand scale that it was not completed until around 1080.

In September 1011 Vikings laid siege to Canterbury and captured Archbishop Alfege, as well as other notable clerics and royal officials. Alfege was held prisoner for seven months and taken to Greenwich, where a ransom was demanded from London for his release. The Archbishop refused to have money paid and he was murdered in April 1012. His body was initially kept in a tomb at St. Paul’s. Bishop Aelfwig backed Cnut’s rival and thus when Cnut became king he, together with Archbishop Aethelnoth, ordered in 1023 that Alfege’s tomb be destroyed and the relics moved under armed guard to Canterbury. Alfege was canonised in 1078. A church dedicated to him was built on the spot he was murdered, where the current building remains as the parish church of Greenwich.

At the end of the first millennium Christianity was gradually reaching Scandinavia and the Danish prince Cnut, born around 990, was baptised and raised as a Christian. After he became King of England in 1016 Danes settled in areas around Aldwych to the west of the city and lasting evidence of this is the continuing existence of St. Clement Danes in the Strand. Other churches of Danish origin are St. Olave Hart Street, St. Bride’s Fleet Street and St. Nicholas Acon, all named after saints popular with Christian Vikings.

It was noted in the Anglo Saxon Chronicles for the year 962 that a great fire destroyed St.Paul’s minster and it was re-founded in the same year. It was destroyed yet again in 1087 and the Normans decided to replace it with what they hoped would be the largest of all Christian cathedrals. The vast new building took over 200 years to complete.

Gundulf, Bishop of Rochester was responsible for the construction of the original Norman Tower of London. At about the same time he also created a church and house at Lambeth on land held by Rochester Cathedral. When the Archbishop of Canterbury travelled to Westminster he normally spent the last night of the journey in his own property at Croydon but while at Westminster lodged at the Rochester house at Lambeth. At the end of the 12th century Lambeth Palace was acquired by Canterbury and thereafter became the official London home of the archbishops.

Sources include: Christopher Brooke ‘London 800-1200’; John Schofield ‘London 1100-1600’; John Field ‘Kingdom, Power & Glory’; Various ‘St.Paul’s – The Cathedral Church of London’; H.D.M.Spence ‘The Church of England. With thanks to Olwen Maynard and Simon Birrell for proof-reading and fact-checking. Image courtesy of the Hawk Norton Collection.

< Back to Religion and Churches