In brief – London in the late-Middle Ages

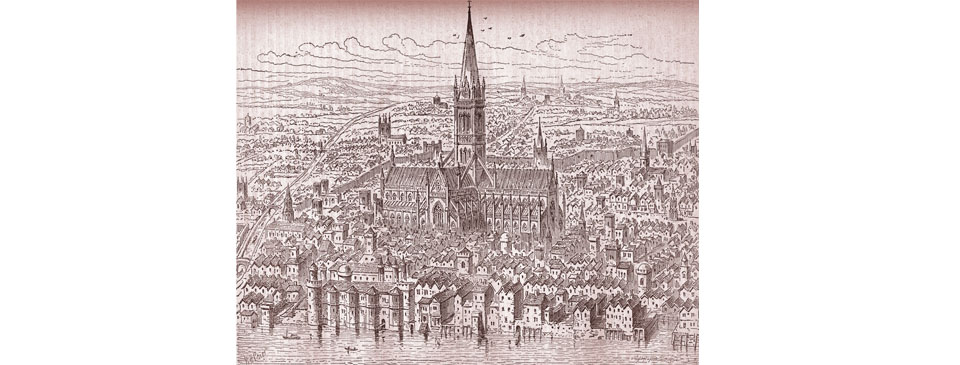

The west side of London in the Middle Ages, looking north. The vast St. Paul’s Cathedral dominates everything around. The city is surrounded by the wall, built on its Roman foundations. On the left the River Fleet flows south to where it meets the Thames. On the riverside in the bottom right is Queenhithe dock. On the centre right runs Cheapside with Cheap Cross in the middle of the street.

By the 14th century London was England’s leading commercial centre, and Westminster the royal and political capital. The population was decimated by the Black Death, which brought about fundamental changes to society. After a century of oppression, England’s Jews were expelled from the country. The printing press arrived in London, which would lead to the wide-spread circulation of knowledge. Wat Tyler led 6,000 men to London to confront the King in the Peasant’s Revolt. Richard Whittington was ‘thrice mayor of London’, immortalized in pantomimes.

By the 14th century London was England’s leading commercial centre and Westminster the royal, political and legal capital. At the end of the 11th century the population of London was less than eighteen thousand but by the first half of the 14th century it had risen to possibly eighty thousand. At that time London was larger and wealthier than other cities such as York, Norwich and Bristol, with four times the number of residents as its nearest rival, around one and a half percent of England’s population.

During the 12th and 13th centuries the governing of England was increasingly centralised at the royal palace at Westminster. King John moved the royal treasury from Winchester and Simon de Montfort and the rebellious barons held the first Parliament there in 1265. Edward I created new departments of government based at Westminster, as well as the Court of the King’s Bench where legal cases were heard. The law courts evolved, with the creation of the Court of Common Pleas. After defeating the Scots Edward transferred their Stone of Scone to Westminster Abbey, to be incorporated into the English coronation chair. In the 14th century, during the reign of Edward III, Parliament divided into the two chambers of the Lords and Commoners and began to elect a Speaker.

London was a major centre of manufacturing, which took place in numerous small workshops around the city in which artisans lived together with their families. Those involved in a particular trade tended to group together in or around the same street, such as Bread Street, Fish Street, Threadneedle Street and Sea Coal Lane.

During the 12th century a number of London guilds were formed by people with some purpose or commonality, something similar to the working men’s clubs of the 19th and 20th centuries. By grouping together within a mutual society artisans and traders could improve and maintain standards, arbitrate in disputes, and fight competition from foreigners. Only freemen were allowed to sell goods as retailers in the city and from 1312 any new freeman had to be certified by a merchant or craftsman of the business in which they operated. Thereafter the most common route to gaining the freedom of the city was through an apprenticeship. During the 14th century members of each trade began to wear a common uniform or ‘livery’ at major ceremonies and the trade guilds became known as ‘Livery Companies’.

Several markets existed in the city, the most important of which was on and around West Cheap (Cheapside) at which all kinds of fresh produce and household goods were available. A number of new markets were established during the mid- and late-Middle Ages, including Leadenhall on the site where it still continues in the centre of the City. Fish was a cheap, plentiful and readily available supply of food and was particularly important because Christians were forbidden from eating meat on Fridays or fast days such as Lent. The fishing industry was therefore very important to London during the Middle Ages. A large variety of fish and shellfish were landed and sold in London, caught over a wide area, including freshwater rivers, Thames Estuary, and further afield.