In brief – London in the late-Middle Ages

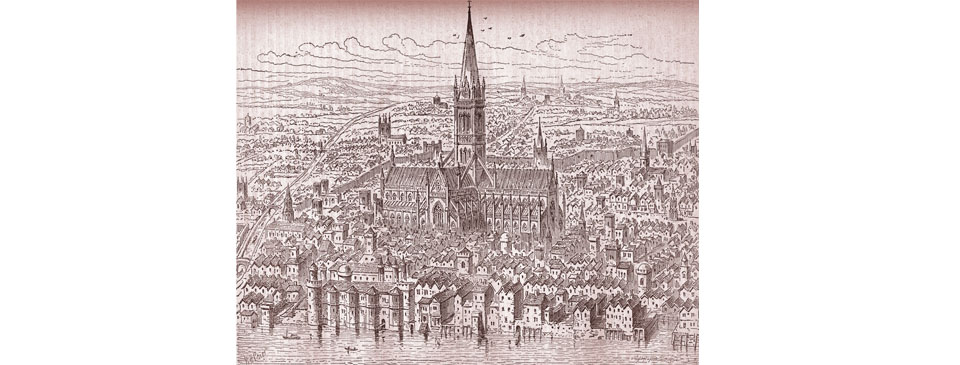

The west side of London in the Middle Ages, looking north. The vast St. Paul’s Cathedral dominates everything around. The city is surrounded by the wall, built on its Roman foundations. On the left the River Fleet flows south to where it meets the Thames. On the riverside in the bottom right is Queenhithe dock. On the centre right runs Cheapside with Cheap Cross in the middle of the street.

During the early days of the Crusades two chivalrous orders of monastic knights that originated in Jerusalem had each established a base immediately outside the London wall. The Order of St.John (or ‘Hospitallers’) built a monastery on land at Clerkenwell and the Knights Templar resided between Fleet Street and the Thames. Their primary role was to support those making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land but endowments ensured that these orders became extremely wealthy. The Knights Templar eventually made a number of enemies and they were dissolved in England in 1308 by Edward II.

In 1381 six thousand men marched on London, led by Wat Tyler, to protest against the introduction of a poll tax by the King’s regent, John of Gaunt, in what is known as the Peasant’s Revolt. The protesters rioted in London, murdering government leaders and members of the royal household. The young King Richard II met the protesters at Smithfield, where Tyler was fatally stabbed by the Mayor of London. Another such rebellion took place in 1450, during the reign of Henry VI, led by Jack Cade.

The most famous of all London mayors was Sir Richard Whittington, immortalised in modern pantomimes as ‘Dick’ Whittington. In reality he was a wealthy mercer, financier and merchant who held office three times at the end of the 14th and beginning of the 15th centuries. Disputes between rival groups, particularly of different types of traders, were frequently fought out in the streets of London. Each mayor was under oath to keep peace in the city so when rioting erupted it was a major embarrassment to the mayor and aldermen and caused great friction with the king. Offenders were often punished publicly, providing Londoners with much amusement. More serious offences would result in public hanging at Smithfield.

The victory of Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 resulted in great celebrations in London. His funeral at Westminster Abbey was a grand affair and a large tomb was erected within a chapel. He was held in such high esteem by the time of his death that it subsequently became a place of pilgrimage comparable to that of a saint.

Pageants were a regular and colourful feature of London life, for political or religious reasons. From 1215 the mayor paraded through the city to swear allegiance to the monarch, a tradition that still continues as the Lord Mayor’s Show. Originally the procession travelled from the Guildhall to Westminster by road but from the 15th century by boat along the Thames. Medieval kings often had a precarious hold on the crown and it was important for them to maintain the support of Londoners. They therefore frequently paraded through London to celebrate significant occasions, such as royal marriages and victories in battle. From Richard II each new monarch processed through the city on their coronation day.

The printing press was invented in Germany around 1450 and by the end of the century printed books were available in London. In the 1470s the Englishman William Caxton spent time in Cologne where he learnt the art of printing and after returning to England set up a press beside Westminster Abbey. In 1477 he published the first book in the English language.

Medieval London was a bustling town of houses, palaces and churches, of workshops and markets, a crowded, dirty and noisy place. Permanent shops selling different types of goods had replaced stalls along Cheapside. In many places vendors also cooked and sold hot food in the streets from trestle tables including bread, hot meat pies or ribs of beef, wine or spiced ale.

The docks and wharves along the river were thriving with trade from around the coast and across to continental countries. By 1500 a third of England’s overseas trade passed through London, rising even further in the following century. In the 12th and 13th centuries sea-borne trade had been controlled by foreigners but by the end of the 15th century they had largely been squeezed out by English merchants.

The wealthy were by then living in certain areas of the city, such as around the Guildhall. That was also where the Livery Companies established their halls, some of which still exist today, although rebuilt in later centuries. The houses of the wealthier craftsmen, merchants or minor aristocracy were being constructed in a mixture of brick, timber and plaster, some up to five stories in height. Bricks were produced in brickfields to the east of London at Whitechapel and Limehouse and timber frames for houses by carpenters at Maldon in Essex, brought to London by boat. Chimneys to let out the smoke from the fires used for cooking and heating for ordinary homes were becoming more common and glazed windows began to take the place of shutters or cloth-covered windows from the late 14th century.

The city had expanded beyond the old Roman walls. It had more or less joined with Westminster westwards along the Strand, where large houses and the Inns of Court then existed. Across London Bridge was the busy area of Southwark on the opposite bank of the Thames. Otherwise it was still surrounded by fields and meadows, with small scattered communities. Riverside villages to the east were occupied with ship building and repairing. Beyond the city gates rows of taverns, monasteries and other buildings lined the roads leading out of London.

With thanks to Ursula Jeffries for help with fact-checking and proof-reading.

< Go back to In Brief: London in the Early Middle Ages or forward to In Brief: Tudor London >