In brief – Late-Stuart London

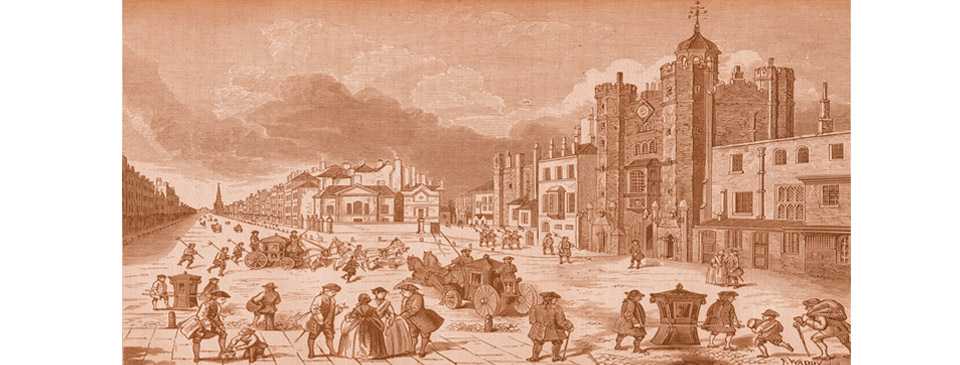

Pall Mall and St. James’s Palace at the time of Queen Anne in the early 18th century. Pall Mall was laid out along the line of where the game of ‘palle-maille’ had been played. The finest houses were on the south side overlooking St. James’s Park.

It took many years to restore London after the Great Fire of 1666 but by the end of the century London the rebuilt city was one of the most magnificent, and the largest, in Europe. It was expanding, with fashionable new suburbs to the west of the old City.

Charles II died suddenly and unexpectedly in early 1685 without producing a legitimate heir. The throne therefore passed to his Catholic brother, who became James II for a mere three years. Fearing an alliance between the two Catholics James and Louis XIV of France, the Protestant Dutch leader William of Orange, who was married to James’s eldest daughter Mary, invaded, landing in the south-west of England. Anti-Catholic apprentices rioted in support on the streets of London and James fled Whitehall Palace. William and Mary jointly took to the throne in the series of events known as the ‘Glorious Revolution’. Henry Compton, Bishop of London, a loyal royalist during the reign of Charles II, played a significant part in the downfall of James II and the succession by William and Mary.

The reigns of William III and Queen Anne were periods of great turbulence in English politics that helped create what we would currently recognize as modern British parliamentary government consisting of opposing parties and a cabinet system.

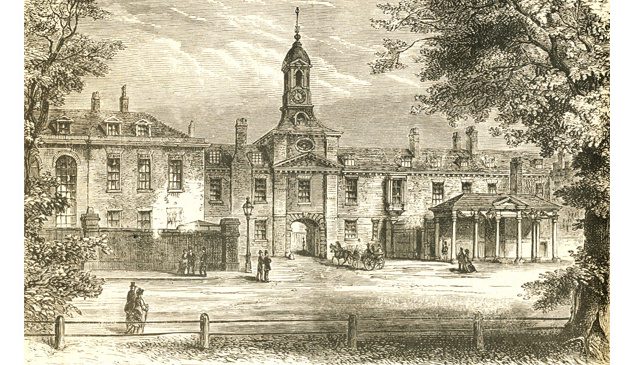

William suffered from asthma and Mary decided that the foggy riverside conditions around Whitehall Palace caused by so many coal-burning fires were not a healthy place for him to live. William took to residing in apartments at Hampton Court while Mary arranged for the purchase of the Earl of Nottingham’s house on the western side of Hyde Park. Christopher Wren was instructed to convert it into what became their new London home of Kensington Palace.

Wars against the French during the reigns of William III and Queen Anne created great momentum to the growth of colonies and trading posts, particularly in North America and the Caribbean, Africa and the Far East, and a greater influence in the Mediterranean. This in turn had a positive effect on the nation’s imports and exports. London was by far the country’s largest port in Britain, handling around three quarters of the country’s entire maritime trade. The first large commercial dock on the Thames was opened on the Rotherhithe Peninsula upstream of Deptford in 1700, known as the Howland Wet Dock. At the centre of Britain’s overseas trade were the joint-stock companies, such as the East India, the Royal African and the Levant. The growth of international shipping created an increasing market for finance and marine insurance. London’s merchants, financiers and marine insurance underwriters were primarily based at the Royal Exchange in the City.

The greater need for funding for the monarch, government and merchants, brought about the foundation of banks, established by gold merchants. By the latter part of the 17th century there were about forty merchant bankers operating in London, lending money and paying interest on gold deposits. A joint-stock company to lend money to the government was initially proposed by the London-based Scottish merchant William Paterson. Legislation was duly drafted and the Bank of England established as a private company in the summer of 1694.

In 1697 a number of stockbrokers were expelled from the Royal Exchange and they continued to do business at Lloyds coffee-house, thus cementing its reputation for that trade. Bulletins regarding shipping were printed and read out from a pulpit within the coffee shop, a tradition that still continues at the Lloyd’s of London building. These included news of departures and arrivals of ships and of maritime disasters. Lloyd’s List began to be published from 1734 giving detailed shipping information and it continues to be a central feature of the modern London insurance market.