In brief – Late-Stuart London

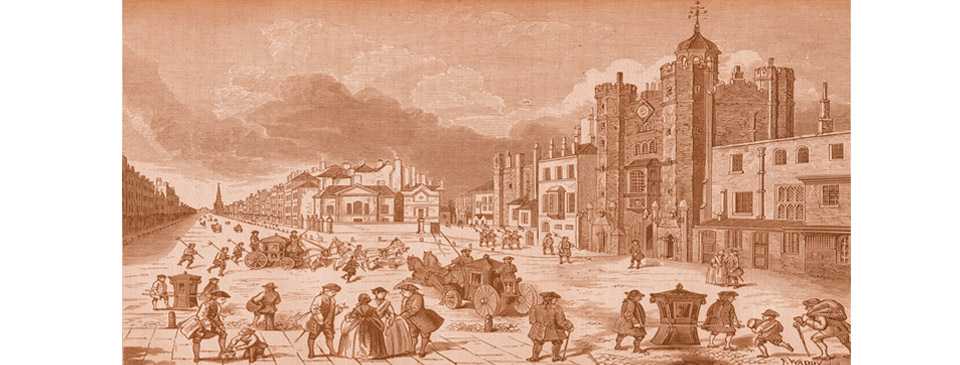

Pall Mall and St. James’s Palace at the time of Queen Anne in the early 18th century. Pall Mall was laid out along the line of where the game of ‘palle-maille’ had been played. The finest houses were on the south side overlooking St. James’s Park.

The Great Fire of 1666 devastated the greater part of the crowded, old, medieval City of London but by the end of the century all except a handful of buildings had been replaced. With the fast-expanding suburbs and the rebuilt City, dominated by Wren’s new St. Paul’s Cathedral, London could probably lay claim to being the most magnificent city in Europe of the time.

In the previous two hundred years London’s inhabitants had increased from around 50,000 to over half a million. At the beginning of that period it barely ranked in the top ten of European cities but at the end of the 17th century it boasted the largest number. It had also increased its share of the nation’s people, containing around one in nine of the entire population. Norwich, then England’s second largest city, contained only 30,000 residents. The country’s largest centre of trade and industry, anyone of any wealth and importance either kept a home or regularly visited London on business, for shopping, entertainment or simply to show their face at the royal court or in high society.

In the mid-16th century three quarters of the population of the London conurbation lived within the city walls. By 1680 the suburbs had grown to the extent that three quarters of London’s residents lived outside the walls. The planned suburb of Covent Garden was created on the land of the Earl of Bedford during the first half of the 17th century. Another development followed at Lincoln’s Inn Fields. These houses were popular with the aristocrats who returned after the Restoration as they were close to Whitehall and St. James’s palaces and away from the bustle of the City. Their popularity led to a boom in fashionable housing to the west of London. A new development slowly grew around Hatton Garden, designed for merchants who wished to live outside of the City. In the first half of the century the Earl of Southampton began planning a new development on his land at Bloomsbury, to the north of Holborn. Delayed during the Commonwealth period, it began in earnest in the 1660s. Once again, this scheme was created around a square but the idea from the beginning was to have an assortment of sizes of house, as well as a market.

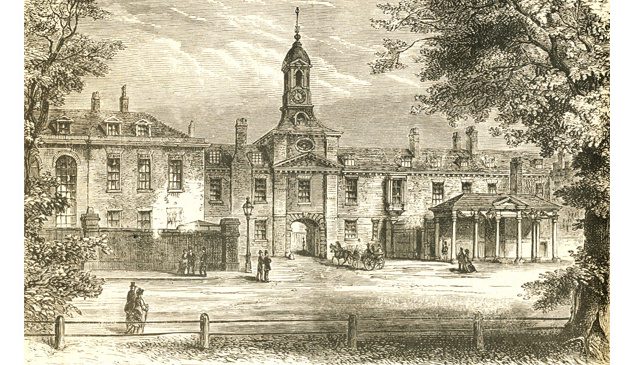

After the death of Richard Baker his widow started to develop the land around their Piccadilly Hall. The country lane that ran west towards the village of Knightsbridge had the advantage of being close to St. James’s Palace and grand mansions began to be built there after the Restoration. The Earl of Clarendon’s house on the north side of Piccadilly was barely completed before it was demolished and the land sold to a consortium of Sir Thomas Bond, Henry Jermyn and Margaret Stafford where they laid out a number of new streets. The Earl of Burlington purchased an uncompleted house on the adjacent land and there built Burlington House as his London home, finished in 1668. The Earl of Berkeley built Berkeley House on another adjoining plot.

The development of Soho from open meadows to a densely-packed suburb occurred from the mid-1670s when Golden Square was laid out with houses for aristocrats, gentry and ambassadors. The streets around Wardour Street and Old Compton Street mostly came into being during the 1680s. Many in modern times still retain the names of developers, landowners, patrons or prominent people of that period. This began in the early decades of the 17th century when the Earl of Leicester built a mansion on what is now the northern side of Leicester Square. Both Golden Square and Soho Square were originally populated by aristocrats and ambassadors. Most of the other streets in the area were completed by the 1690s, with buildings designed to accommodate the workshops and homes of tradesmen and artisans serving the nearby gentry.