In brief – Late-Stuart London

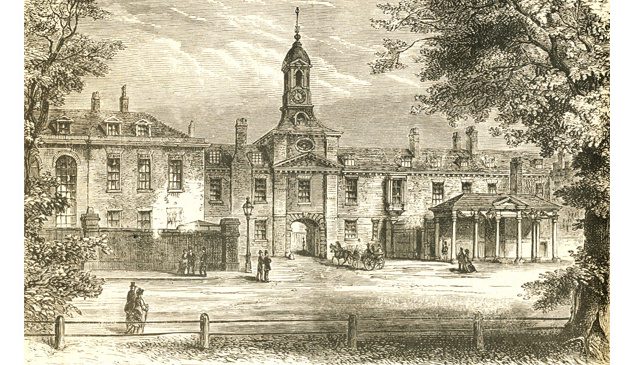

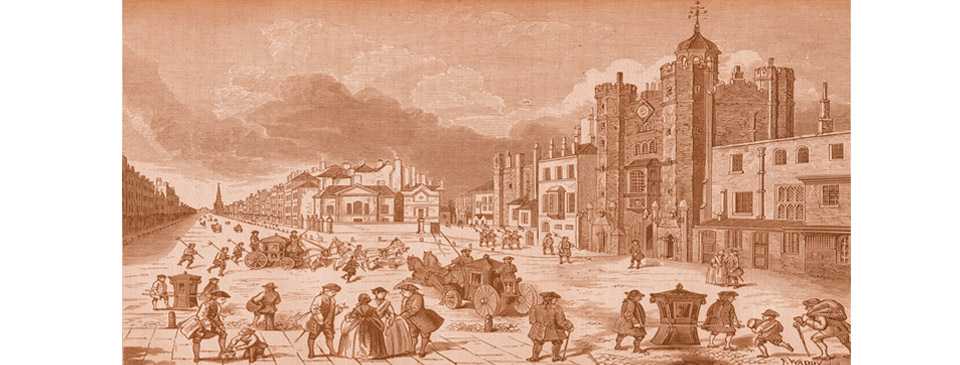

Pall Mall and St. James’s Palace at the time of Queen Anne in the early 18th century. Pall Mall was laid out along the line of where the game of ‘palle-maille’ had been played. The finest houses were on the south side overlooking St. James’s Park.

The developments at Bloomsbury, St. James’s, north of Piccadilly, and Soho were mostly initiated by wealthy landowners who were involved in decisions on the general layout. They then sub-divided the land around the squares and along the streets into plots that were leased for a period of time by the speculators who erected the buildings. At the end of the lease-period ownership of the building reverted to the landowner. The most famous of the speculators were Nicholas Barbon, a man notorious for his aggressive business tactics, and also Richard Frith.

As the size of London’s middle class grew so the number of people living in large, multi-storied houses increased. These terraced houses usually included a lower ground floor for a kitchen and laundry-room where the servants toiled, as well as a garret in the roof where they slept. The small basement level courtyard that allowed light into the lower floor was known as the ‘area’. At ground level it was surrounded by attractive iron railings in order to prevent passers-by falling down into the area. Most terraced houses of the better sort had a small garden or courtyard at the rear. The rebuilding of the City and the new developments were undertaken using bricks manufactured from clay in fields north of London, such as around Spitalfields (hence the name Brick Lane).

In 1696 the government, in dire need of additional income to pay for the war against France, and with rising inflation caused by money-clipping, introduced a window tax. As a result, many house-owners bricked up windows to avoid paying, while others, who wished to flaunt their wealth and allow in the maximum amount of light, built houses with a large number of windows to differentiate themselves from the lower classes.

The Great Fire displaced a large number of working people from the City who were unable to afford to return. New regulations introduced after the fire prevented the most dirty and dangerous manufacturing from taking place in the City and those workers generally moved east or south. Aristocrats and the wealthy were attracted to the new developments in the west. By the end of the 17th century London, from Westminster to Whitechapel and down to Southwark, had divided into districts populated by different classes of people. Generally speaking, the west was the royal court and aristocracy, Soho a district of artisans, the City of commerce, the east of shipping, and Southwark of manufacturing.

Charles II intended to rebuild the old Tudor royal palace at Greenwich in the more modern style he had witnessed during his years in exile. He commissioned a building to compliment the nearby Queen’s House but by 1669 it was only part-complete when he ran out of money. During her reign Mary II was moved by the sight of injured sailors returning from the Battle of La Hogue in 1692 and set about founding a naval hospital, similar to the Royal Hospital for soldiers at Chelsea. The Royal Naval Hospital, incorporating the unfinished Greenwich Palace but, lacking adequate funding, was not completed until the early 18th century.

During the latter part of the 17th century and early 18th century there was a great influx of Protestant immigrants to England, fleeing war and persecution in Continental Europe. Many were industrious artisans who brought with them skills new to this country, such as silk-weaving, glass-blowing and clock-making. The largest single group were the Huguenots from France who arrived by the thousand to escape persecution by Louis XIV. Greeks arrived when their homelands were invaded by the Ottomans and a small community lived in the new suburb at Soho. Sephardic Jews arrived from Spain and Portugal and Yiddish-speaking Jews from Eastern Europe via Amsterdam. These latter groups set up synagogues on the east side of the City, notably the one at Bevis Marks.