In brief – London during the mid-19th century

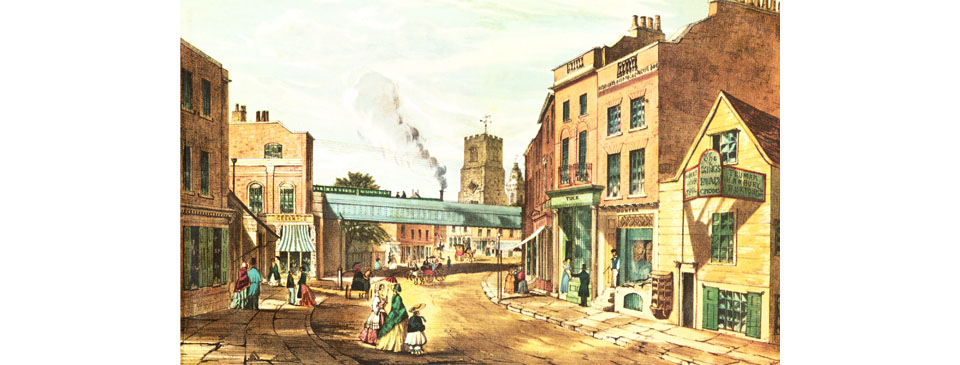

A train from Camden passes over Mare Street, Hackney on the new North London Railway in this engraving from the early 1850s. The railway was built to provide a link between the London & Birmingham Railway at Chalk Farm and the East and West India Docks. The section through Hackney was completed in 1850 and the entire line opened in January 1852.

The census of 1841 showed that about four percent of London’s population was of Irish origin and many were amongst the poorest in the metropolis. Thousands worked in the docks and therefore the biggest groups of Irish were to be found in the villages on the eastern side of London. Another large group lived in extreme poverty in the rookery of St. Giles and made up a sizable minority of the capital’s beggars.

Political upheaval in Continental Europe brought waves of immigrants from France, Germany, Italy and Eastern Europe to London in the 19th century. Between 1841 and 1851 the number of foreigners living in the metropolis doubled from about 13,000 to 26,000, many of whom were hard-working economic migrants. The more middle-class of these immigrants settled in Soho and Fitzrovia while many of the working-class lived around Whitechapel and Mile End.

There were increasing numbers of poor in London, often living in squalid conditions, and numerous charities were formed in the 19th century to give help. Aware that relatively few amongst the needy were practicing Christians, many of these new charities were formed by Evangelical religious groups with the dual purpose of providing aid and converting non-believers.

New charitable religion-based schools for the poor were established in London in the late 18th century and such institutions later became known as ‘ragged schools’. Lord Shaftesbury formed the Ragged School Union in 1844, encouraging their establishment in the poorest areas. Several years later there were over 15,000 attendees in London in more than eighty schools.

When London’s first institution was founded to provide an education similar to the universities of Oxford and Cambridge it was created as a secular body, much to the indignation of the Anglican establishment. They quickly created the rival King’s College, with the backing of the Duke of Wellington. Initially neither University College nor King’s had the ability to confer degrees, so the University of London was formed as an examination board in 1836.

London had always had a great divide between the rich and poor and the Victorian era, prior to the introduction of social reforms and welfare programmes, was perhaps the zenith of that division. In earlier centuries, when the town was smaller, both ends of the spectrum lived side by side. As London expanded, the rich, poor and middle class increasingly came to reside in separate areas. By the early 19th century London had large districts of old, decaying housing known as ‘rookeries’, places of squalor and deprivation that more or less formed a complete circle around central London and Westminster.

In 1836 Parliament set up the Select Committee on Metropolitan Improvements to consider London’s problems, and their answer to solve both traffic congestion and the rookeries was to build new roads through the slum districts. The priority areas chosen were St. Giles (where New Oxford Street and other roads were created), Spitalfields and Whitechapel (Commercial Street), and the Devil’s Acre (Victoria Street). The new roads were created but there was no answer as to where the former inhabitants would live. They simply moved to even more densely-packed slums nearby.