In brief – London during the mid-19th century

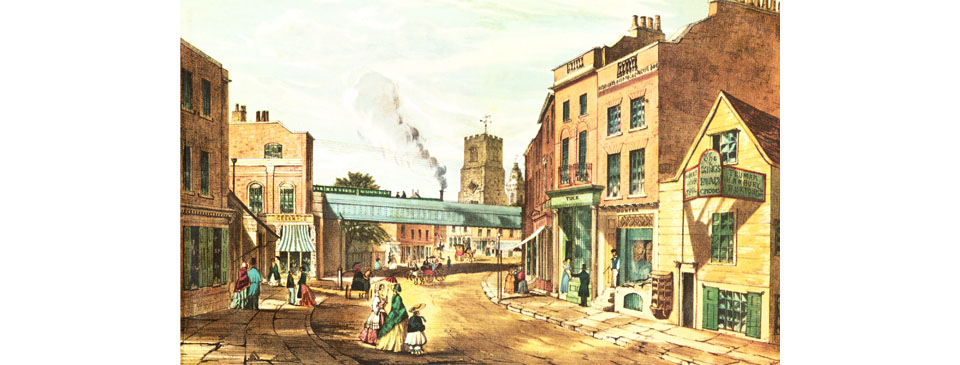

A train from Camden passes over Mare Street, Hackney on the new North London Railway in this engraving from the early 1850s. The railway was built to provide a link between the London & Birmingham Railway at Chalk Farm and the East and West India Docks. The section through Hackney was completed in 1850 and the entire line opened in January 1852.

The water supply and sewage system could not keep up with the ever-increasing population of the city, especially in the poorer and more overcrowded areas. During the mid-19th century London was blighted by water-borne cholera epidemics, the first of which occurred in 1832. There were also numerous outbreaks of other diseases, including typhus, influenza, measles, rabies and smallpox. For many years experts believed diseases were carried by miasma – ‘bad air’. It was not until the 1850s that the surgeon Dr. John Snow could prove that London’s polluted drinking water carried the cholera bacteria.

Few homes of the working classes had hot and cold running water, let alone a bath. By the 19th century cleanliness was becoming recognized as important so public baths for bathing and washing clothes were opened by charitable organisations. The government soon took up the idea and the Public Baths and Wash Houses Act was passed in 1846, giving local boroughs the authority to raise finance and open baths. By the second half of the century they were a common feature of the entire metropolis.

Central London’s churches had run out of space in which to bury the dead and in the 1830s and ’40s private companies were authorized to open large new cemeteries in and around London’s suburbs. The first was at Kensal Green, established by the South Metropolitan Cemetery Company, and six others followed at West Norwood, Highgate, Nunhead, Stoke Newington, Brompton and Stepney. New legislation allowed local vestries to open similar facilities beyond their own boundaries, the first of which were those of St. Pancras and Islington whose new cemeteries were at Finchley.

With little in the way of policing and regulation, London had become a hunting-ground for criminals throughout the 18th and early 19th centuries. Anyone walking the city’s streets was prey to skillful pickpockets, tricksters, and street-robbers. As London rapidly increased in size during the 19th century, however, and householders more prosperous, it became advantageous for criminals to transfer their activities to house- and warehouse-breaking. As shops became larger and with more goods, shop-lifters – mainly women – became increasingly industrious.

The Metropolitan Police was created in 1829 to deal with fighting crime and keeping the peace throughout London, except for the City. In 1839 the Marine Police Establishment, which had been established at Wapping to fight theft of goods from ships in the Port of London, became the Thames Division of the Metropolitan Police. The jurisdiction of the force was enlarged in 1839 to cover an area with a radius of fifteen miles from Charing Cross and the number of officers increased to four thousand three hundred. In 1842 a Detective Branch was created, later named the Criminal Investigation Department. The City of London police was established in 1839 with a detective force from 1848.

London had long been the main centre of manufacturing in Britain but that began to change as the Industrial Revolution gained momentum. New large-scale manufacturing processes that relied on coal and water-power were established in the Midlands and north of Britain, closer to coalfields and fast-running water. Nevertheless, London still remained the nation’s single largest manufacturing city, with by far the most extensive pool of labour. Over half a million workers, or a third of London’s population, were employed in manufacturing in one form or another by the latter part of the 19th century.

There were ever-greater numbers of waged and unskilled employees working in factories, garment manufacturers, workshops, shops and other businesses and protests about working conditions and remuneration began to take place on a more organised basis. Withdrawal of labour became the favoured weapon of protest instead of the random violence of earlier times. As the 19th century progressed there was a growing sense amongst radicals that collective action could improve conditions for the employed and unemployed.