In brief – Plague and Fire

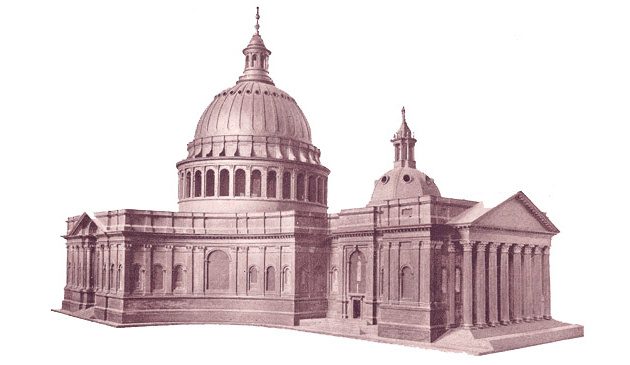

The rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral in the late 17th century under the direction of Sir Christopher Wren. Work began in 1673, seven years after the fire, and was to take 35 years.

Thoughts of those in authority quickly turned to the rebuilding. The Mayor and aldermen were in favour of a completely new layout, to which the King agreed, stating that he hoped to see a more beautiful city rise from the ashes. Charles invited ideas and issued some initial guidelines and instructions. A number of plans were forthcoming, notably from Robert Hooke, John Evelyn, and the one most favoured by the King from Christopher Wren.

There were numerous complications in planning a new city on the ashes of the old, however, and in particular the property rights of freeholders. Laws were required to make changes and a body of Commissioners was created by the King and City of London, including Wren and Hooke, to consider the details. An early decision was that former streets should be widened and that property-owners would be compensated for any loss of land. During the winter of 1666-1667 committees met to discuss and determine many points, including the width of new streets and building regulations, which were to be laid down in the Rebuilding Acts. Individual streets were graded, and types and size of houses prescribed according to those streets. The Bill ordered that all exterior walls of each building should be made of brick or stone. To prevent flooding, and to reduce the steep descent of streets that ran down to the river, Thames Street and the ground to its south was to be raised by three feet. No buildings were to be constructed within forty feet of the waterside alongside the entire length of the City, thus creating a wide Thames-side quay.

Fire insurance did not yet exist, so property-owners, including the City of London and parish churches, had lost their properties. How could the cost of rebuilding be paid? Parliament found part of the answer by introducing a London coal tax in January 1667. It was used to pay for the road-widening compensation, to buy the land for the new quay along the north bank of the Thames and either side of the Fleet, as well as for new prisons.

Property-owners had lost their buildings but leaseholders had lost their homes. According to lease agreements, tenants were normally responsible for making good any damage and liable to continue paying rent, even though the household had been destroyed. It was a difficult legal conundrum and Parliament created the Fire Court to arbitrate in each dispute between landlord and tenant. The first case was heard in February 1667, with judges sitting from eight o’clock each morning. By December 1668 fourteen judges heard over 800 cases. The powers of the court were extended until 1676.

Parliament anticipated that there would be an unprecedented demand for construction workers and prices could spiral out of control, which would not only disadvantage Londoners but would slow down the rebuilding. To limit the problem the Rebuilding Act set aside for seven years the need for builders to be a member of a Livery Company and ensured that all tradesmen were prohibited from charging exorbitant amounts for labour or materials.

Before any work could begin a survey was required in order to establish the boundaries of those former properties, which was not an easy task when almost everything had been obliterated and buried under piles of debris. It was decided that surveyors were to be appointed to stake out the new streets and ensure that each new building was erected in accordance with the law. That task was given to Robert Hooke and Peter Mills. Between them they marked out eleven miles of roads. The first building survey was carried out in May 1667 and the last at the end of 1671, by which time almost 8,400 had been dealt with.