John Rennie’s London Bridge

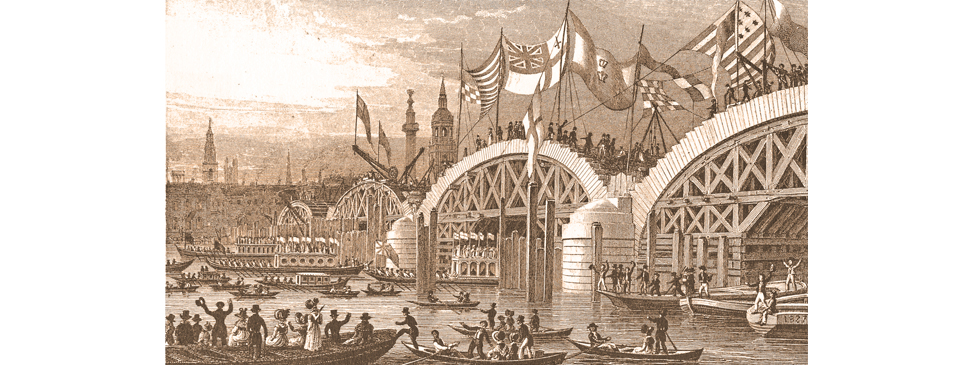

Barges of the 1827 Lord Mayor’s Parade pass under the new London Bridge while building work was underway. The design was by John Rennie but there was so much procrastination before a decision on its construction that he died before work began.

Sometime after the completion, Sir John Rennie (the Younger) wrote of the difficulty of placing the cofferdams for the piers and abutments due to the riverbed…

covered with large loose stones carried away by the force of the current from the foundation of the old bridge… The difficulty was further increased by the old bridge being left standing to accommodate the traffic whilst the new bridge was building; and the restricted waterway of the old bridge occasioned such an increased velocity of the current as materially to retard the operations of the new bridge, and at times the tide threatened to carry away all before it.

Construction took seven and a half years, employing up to 800 workers. Forty men were killed during that time due to the problems mentioned by Rennie. The total cost of the bridges and approaches was £2,500,000. Of that amount, a million pounds was raised through a tax on coal and wine and nearly £200,000 contributed by the government.

The different alignment, slightly upstream, caused the City Corporation great difficulty, with new approaches having to be created on both sides of the river, costing twice that of the bridge itself. Wren’s St. Michael, Crooked Lane church had to be demolished as well as the old Boar’s Head tavern in Eastcheap (which featured in Shakespeare’s Henry IV), and Fishmongers’ Hall. On the south side, Borough High Street was widened between the bridge and the Town Hall, in addition to creating a new section of Tooley Street. In the City, Upper Thames Street, Fish Street Hill, Eastcheap, King William Street, Princes Street, Lothbury, Gresham Street, Moorgate Street and Threadneadle Street were all affected in some way.

Completed in 1831, the new London Bridge was opened by King William IV (a month before his coronation) and Queen Adelaide in a major ceremony that August, with the firing of canons and ringing of church bells. It took the form of a water procession that included the royal barges and eight City barges. Thousands of onlookers lined the riverbanks and took to various craft. As the royal couple descended to their barge at Somerset House the cheering was described as “almost deafening”. After arriving at the bridge they walked across, starting at the northern end. Upon reaching the Surrey side entertainment was provided by a hot air balloon and its occupants ascending into the sky. The opening ceremony was followed by a banquet at the City end of the bridge for 1,500 people.

The Duke of Wellington had aided the City Corporation in steering the necessary Bill through Parliament. He was invited to the opening ceremony but declined, knowing that his attendance would be unpopular and cause a disturbance due to his opposition at that time to the Reform Bill being debated in Parliament and the country at large. Instead, as a mark of their appreciation, the City erected a bronze equestrian statue of the Iron Duke at the front of the Royal Exchange.

On its first day 200,000 pedestrians crossed the bridge, so many that passage had to be restricted in one direction only, from north to south. John Rennie the Younger was knighted for his work, an honour his father had previously refused.

The demolition of the old bridge, the foundations of which had survived for over 600 years, took two years. During the construction of the new bridge and demolition of the old a silver Roman statuette of Harpocrates (now in the British Museum) was found, as well as a number of Roman and medieval coins. Much of the old bridge was sold as souvenirs. Four alcoves from the 1762 bridge are located at Guy’s Hospital, Victoria Park, and in East Sheen. The timbers of the old bridge were sold to the New River Company to line their new reservoirs at Stoke Newington.

Rennie’s bridge lasted until the early 1970s when it was replaced by the current crossing. The discarded granite exterior blocks were purchased by a property developer and shipped to Lake Havascu City in Arizona to become an attraction for a retirement home complex. The blocks were clad onto a concrete structure that recreated Rennie’s bridge.

Sources include: Charles Welch ‘History of the Tower Bridge’ (1894, courtesy of the collection of Hawk Norton); Peter Matthews ‘London’s Bridges’; John Summerson ‘Georgian London’; John Pudney ‘Crossing London’s River’; Robert Ward ‘ London’s New River’.

< Back to Bridges and Tunnels