Londinium, the capital of Britannia

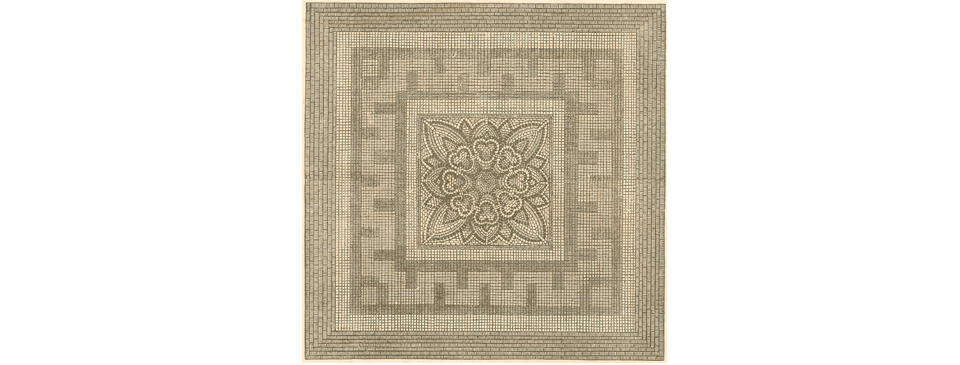

Two sections of Roman pavement, including this one, were discovered in 1841 at about 12 to 14 feet in depth when the French Protestant Church in Threadneedle Street was being demolished. Coins depicting Agrippa, Claudius, Domitian, Marcus Aurelius and the Constantines, together with fragments of frescoes, were also found. These pavements are now preserved in the British Museum.

From the beginning, Londinium was a town that existed for trade. Initially much of its requirements were imported from elsewhere but as time went on workshops and industry grew to produce goods for the local population. The remains of mills, slaughterhouses, and a glassworks have been discovered as well as many tools for metal-working, carpentry, engineering, building and shipping. Britain was a major source of wool and it is most likely that Londinium was a centre of the textile and leather industries. Many everyday household items such as needles, scissors and cooking tools needed to be produced by specialist workshops. Some book publishers probably operated, producing hand-written books made by calligraphers. Publishing also created a demand for specialist trades, including the production of vellum, styli and ink.

Some Roman tools preserved in the bed of the Walbrook and discovered in modern times are very particular in nature and would have been manufactured in very small quantities by specialist workshops, with only a limited number of producers of such tools in the entire empire. The relatively large size of Londinium means that some such specialist manufacturers were almost certainly located there, creating machinery, tools, instruments and other goods to order from around the province and perhaps further afield. The Romans operated an efficient postal service, enabling specialist goods to be ordered by and delivered to people around Britain.

In cases where goods were manufactured within the town and sold direct to the public it was normal that the workshop fronted on to the street and the owner of the business and his workers lived in a room behind or on floors above. Those items that were imported for resale are more likely to have been sold at the forum market. Much of the manual labour involved in industry was carried out by slaves and any established tradesperson probably owned at least several slaves for that purpose.

Trades were regulated by trade associations, or collegia, which were an earlier version of the guilds and livery companies of medieval London and shared many of the same functions. Each association recruited a senior and respected member of the community as its patron who was able to give it authority and speak on its behalf whenever required. Each tradesperson required a licence to carry out their business and the trade association ensured there was the correct balance between those licensed to carry out the work in relation to the amount of business available. They ensured standards of work and protected their members against complaints from customers. The association took care of certain aspects of welfare, such as funeral expenses, retirement costs and maintenance for widows.

Even at its largest Londinium was small enough that it was not too much trouble for the average person to walk from one destination to another. There were different types of transport for the affluent and senior officials. A sella portatoria was a portable chair, similar to a sedan chair, that could be carried by men holding poles. The wealthy owned their own and others could hire them in the street in the same way we hire taxis today. A lectica worked on the same principle of being carried but was larger and more like a portable bed where the occupants reclined on cushions and were carried by four, or up to eight, bearers. A two-wheeled carriage known as an essedum was also used in Londinium. Wagon-based commercial traffic tended to block roads in towns in Roman times as much as during the Middle Ages. In Rome such commercial traffic was generally banned during the day and that was probably also the case in Londinium.

Most Roman towns were fed with fresh water by means of aqueducts but there is little evidence of their existence in Londinium, probably because there was already a plentiful supply from the many streams and wells. The remains of several wells have been discovered in London during modern times, from which the Romans drew water, using wooden buckets on continuous iron chains powered by men or animals. Sewers were certainly installed.

The diet of Roman London was primarily meat and grain. Meat was brought into town on the hoof from far and wide and animal fat was also used to produce oil. Pigs could be reared in the nearby forests. Poultry, eggs and honey were probably also produced locally. Grain came from further afield, down the Thames and River Lea, oysters from beds in the Thames Estuary, and salt from the Essex coast.

One of the duties of each Roman town authority was to provide education for the young, with even the smallest having provision for elementary schools. Larger towns such as Londinium provided education up to university level. Teachers and professors were highly respected and well-paid in comparison to labourers. It would appear from remains of excavated materials that many or most inhabitants of Londinium were literate by the end of the 1st century. Copies of invoices have been found and, perhaps more telling, even sophisticated graffiti etched into bricks by building labourers.

Personal fitness and cleanliness were important to the Romans. Londinium contained many public baths, which operated in the style of the later Turkish baths where the bather alternated between a hot bath, an oil massage, a sauna, and a cold bath. Ordinary baths were known as balnea and a town of the size of Londinium would have had one in each neighbourhood. There were probably several larger establishments in Londinium known as thermae, which were the equivalent of modern gymnasia or fitness centres, where attendees could take part in various sports and excercise including boxing, weight-lifting and gymnastics. They were places where the more affluent men and women could meet and socialise and were equiped with drinking lounges. The reamains of two thermae appear to have been located at Cheapside and Huggin Hill.

Sports and entertainment were popular and all towns of any size had a public amphitheatre and at least one theatre. Londinium’s first amphitheatre for sport and entertainment was constructed of wood in around 75AD and located to the south-east of the fort. It was replaced in the early 2nd century at the time of Emperor Hadrian’s visit by one constructed of stone and brick, located where the Guildhall now stands.