London and Westminster during the Norman period

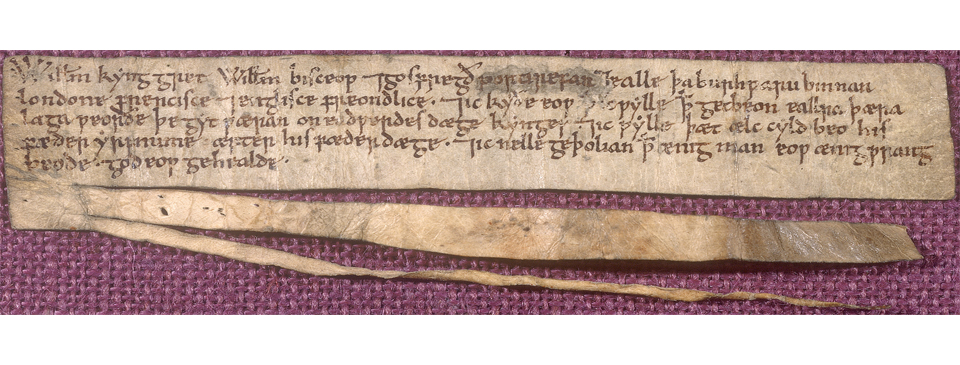

The charter of reassurance issued to the people of London by King William after his coronation, probably in early 1067. It has been held in the records of the City of London since that time. It is written on vellum and the slits in the lower half were to tie the King’s seal. © City of London, London Metropolitan Archives, used by permission.

Following the Norman Conquest of 1066 London continued much as before, except with a new French ruling class. It was still not the most important town in the kingdom but was important enough that the King granted the town’s commune important rights. The nearby Palace of Westminster was starting to be the base of the king’s civil servants.

There was no need for a capital during William’s the Conqueror’s reign since government took place and laws decided by the King and his courtiers wherever they went. William and his successors were not based in one place and travelled around the various towns and palaces of their lands in England and Normandy. Yet London, with its sea-route to the Continent, was a town conveniently situated for a leader with an Anglo-Norman empire to rule. William generally held court at Westminster for the great feast of Whitsun when he would entertain the leading barons and clergy of his lands. However, he also had equally important palaces at Gloucester and Winchester, the latter being where the royal treasury was kept.

During the years after the conquest William rewarded his Norman noblemen with land around England. Almost all bishops were brought from Normandy, although the sitting Bishop of London was already a Norman even before the Conquest.

In case of uprising from London’s population, three stockades were constructed around the edge of the city. Two, on the west side, were built and occupied by Norman knights. The third, outside the south-east side was constructed on William’s orders as a royal castle and that became the Tower of London.

But London was both powerful and wealthy and William needed its income from taxes. It was necessary for him to guard himself against uprising but also gain the allegiance of the town’s population. As a result of negotiation by William, Bishop of London, the King issued a charter of reassurance soon after his coronation, which reads:

William king greets William the bishop and Geoffrey the portreeve and all the citizens in London, French and English, in friendly fashion; and I inform you that it is my will that your laws and customs be preserved as they were in King Edward’s day, that every son be his father’s heir after his father’s death; and that I will not that any man do wrong to you. God yield you.¹

In other words: French and English people should live together in London in peace; that the city may continue to use the laws under which it had previously been governed; that the king would not dispute the inheritance of property; and that he would undertake to protect it from attack. Although a Norman, Bishop William had been appointed by Edward the Confessor prior to the conquest. Geoffrey the portreeve (tax collector) was a newly-arrived Norman. The document was written in English by a native scribe and contains William’s seal. Centuries later, during the Middle Ages, it became a tradition for the mayor and aldermen of London to visit St. Paul’s Cathedral to pray for the soul of Bishop William for his efforts in obtaining the charter from the King.

Despite the conquest, life in the city continued more or less uninterrupted as before, except that plots of land were given over to Norman noblemen. Ships continued to unload at Billingsgate, Dowgate and Garlickhythe, and the markets at Eastcheape and Westcheape remained busy and noisy. The oldest-surviving record of the names of London’s aldermen was written in around 1127 and shows that 60 years after the conquest the majority had English names. Although most of the town’s population of between ten and fifteen thousand were Saxon, it was a very cosmopolitan place where Normans, French, Norwegians, Danes, Germans and Flemings mingled.

William knew of the importance of the Jews of Rouen in Normandy for finance and invited them to London. A Jewish Quarter began to grow to the south-east of the Guildhall where it remained for the next two centuries.

As part of the Norman empire, with royal links to Flanders, and without serious threat of attack from Vikings, London’s overseas trade flourished. New wharves were created along London’s riverbank, as well as a new parallel road, the modern-day Upper and Lower Thames Streets.

Inhabitants often left their fires burning all night to keep warm and to save the work of re-kindling in the morning, resulting in many disasters in a town constructed of wood. After an extensive blaze had destroyed many buildings in 1077, including the original Tower of London, William issued an unpopular decree that all fires must be extinguished at night, described as a “cuevrefeu”, the origin of the English word ‘curfew’. Nevertheless, only ten years later “the holy church of St. Paul…was burnt down, as well as many other churches and the largest and fairest part of the whole city” according to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle.

Following its destruction in 1087 it was decided to build St. Paul’s on the same site but on a much grander scale. It was so large that it took over 130 years to complete, dwarfed all other structures in the city, and could be seen from miles around. The Norman building was designed in the Romanesque style.

After the death of William in 1087 the English throne passed to his second son, William Rufus, bypassing the eldest son Robert. After ten years on the throne William II ordered the construction of a great new hall as an extension to the Palace of Westminster and it was completed in time for him to hold court there at Whitsuntide 1099. By the standards of the day the great Westminster Hall was a vast building, certainly the largest hall in England and possibly the whole of Europe. Its size was such that the King could hold court, as well as the largest state banquets and ceremonial occasions.

Even by the late Norman period Westminster was considered one of the most important of the royal palaces. Over time the business of ruling England became more complex and the King devolved duties to a growing bureaucracy. It was less convenient for his officials to be continually travelling with the royal court and permanent offices began to be established for them. During the time of William II the Court of Exchequer, responsible for the accounts of the Treasury, began to conduct its business from the Great Hall at Westminster, with its clerks housed close by. The head of the Exchequer, the Chancellor, was also responsible for the creation and maintenance of laws.