London and Westminster during the Norman period

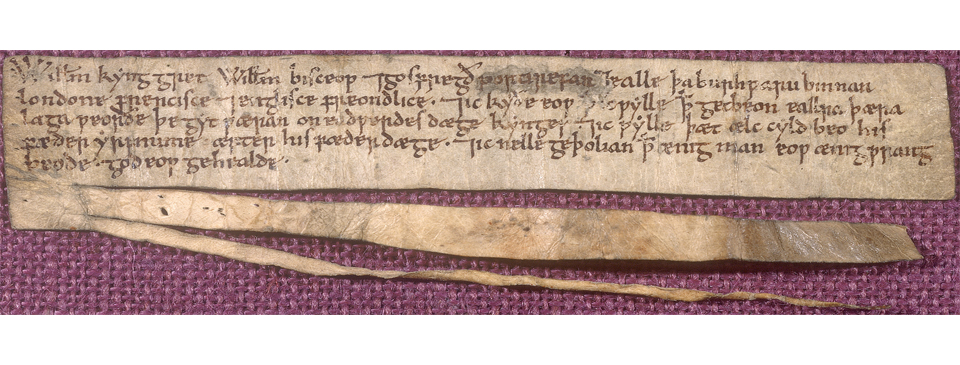

The charter of reassurance issued to the people of London by King William after his coronation, probably in early 1067. It has been held in the records of the City of London since that time. It is written on vellum and the slits in the lower half were to tie the King’s seal. © City of London, London Metropolitan Archives, used by permission.

In the first half of the 12th century a new charter was granted to London by the king, marking an important early step in the city gaining self-government and other freedoms. Among other things it gave Londoners certain rights: to appoint their own sheriffs; for citizens to be tried exclusively by the courts of London; that members of the royal court would not have to be accommodated; to be free of tolls throughout England and its ports; that the king will everywhere uphold Londoner’s rights; and to reconfirm London’s hunting rights in the Chilterns, Middlesex and Surrey. Furthermore, the annual tax (the ‘farm’) that was paid collectively by London to the king was reduced to £300 and the citizens exempt from several other forms of tax.

There is debate as to exactly when the charter was granted and by which king. The original document that would have contained the royal seal is no longer in existence and the text comes from copies of 14th century origin. During the reign of Henry I, successor to William II, London’s ‘farm’ – the total amount of annual tax to be collected from the town – was over £500 and it seems remarkably generous of Henry, a king not noted for his generosity, to reduce it to a mere three hundred pounds. However, in 1133 there was a devastating fire in London and it seems likely that revenue was falling short of previous expectations, with perhaps some arrears owing. Possibly this document accepts the reality of the situation, or perhaps the London citizens were winning the right to appoint their own sheriff – the tax collector – due to some earlier confrontations. Another theory is that Henry was seeking support from London in the campaign for his daughter Matilda to succeed him. A counter-argument is that the charter was really granted by King Stephen, a weaker king who was in greater need of London’s support.

Henry I died without an uncontested heir, leading to civil war known as ‘the Anarchy’ as his daughter Matilda and nephew Stephen fought over the crown. London backed the latter, who most needed the city’s power and wealth in his struggle to gain the throne. However, Stephen was captured at the Battle of Lincoln in 1141 and Matilda moved on London with her army. Without any alternative, leading citizens of London rode out to meet her at St. Albans to negotiate terms before escorting her to Westminster.

To strengthen her position against any further disloyalty from Londoners Matilda granted rights and lands to the powerful Geoffrey de Mandeville, Earl of Essex. He was appointed Sheriff of London, Middlesex, Essex and Hertfordshire, with control of the Tower of London. To further punish London for their allegiance to Stephen she demanded payment from the wealthiest amongst them. It was too much for Londoners. Stephen’s wife marched on the city with an army and was allowed through the gates. The people rioted, church bells rang out and Matilda and her retinue fled to Oxford. The end of Matilda’s claim to the English throne came when her forces were defeated at the Battle of Faringdon in Oxfordshire in 1145, at which Londoners also played a part. In 1148, with Stephen firmly on the throne, his son Eustace died unexpectedly and by 1153, the year of his death, Stephen acknowledged Matilda’s son Henry Plantagenet as his heir.

By the middle of the 12th century London, abandoned after the Roman occupation and re-established by Alfred the Great, was once again one of England’s major towns and ports, dominated by the Tower of London in its south-east and the vast St. Paul’s Cathedral in its west. The rebuilding of the bridge by the Saxons had formed a barrier past which the largest sea-going ships could not easily pass, creating an additional need to unload at London. As the only dry crossing point of the Thames in the south-east travellers found it more convenient to pass through the city than elsewhere. The creation of new wharves by the Norman riverside landowners, as well as the ever-increasing size of ships arriving to unload, was turning London into a major port. The separation of England and Normandy during the reign of King Stephen was only a short-term setback to London’s trade, soon to be reversed when Henry II took the throne in 1154. Foreign merchants had established riverside bases for the importing and exporting of goods and London merchants had obtained charters from the monarchy that put them in a favourable position relative to other ports in England. Westminster, still a separate community to the west of London, was already established as a major royal palace, with the country’s largest ceremonial hall and a leading religious centre. However, London and Westminster combined, with a population of around 18,000, could still not be considered as important as other towns in the king’s territories. Winchester, established as his main town by Alfred the Great in Saxon times and still home of the royal treasury in the early Middle Ages, could be argued to be the ‘capital’ of England and Boston was at that time still a larger port.

¹ Translation: A.J.Robertson, Laws of the Kings of England from Edmund to Henry I, 1925

Sources include: Christopher Brooke ‘London 800-1216’; John Schofield ‘London 1100-1600′; Gustav Milne ‘The Port of Medieval London’; John Richardson ‘The Annals of London’. With thanks to Ursula Jeffries for help with proof-reading.

< Back to Saxons, Vikings and Normans