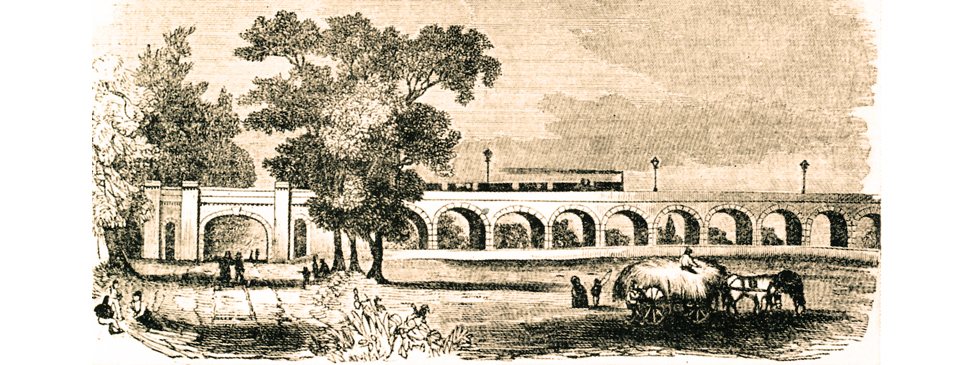

London’s first railway

The London & Greenwich Railway ran along a four-mile long viaduct from Tooley Street on the south side of London Bridge. Much of its route was still rural as can be seen here where the line passed over Spa Road at Bermondsey.

The route of the London & Greenwich Railway would require it to pass through an already congested area, across various roads, and over the Surrey Grand Canal, so it was decided to build it on a viaduct of nearly 900 arches, almost four miles long. That point was, and remains, quite remarkable and it is still the country’s longest set of arches and the longest to be listed (Grade II). It was necessary to create ‘skewed’ arches over the existing roads to preserve the angle of each road. Six million bricks were eventually used to construct the viaducts, up to 100,000 each day. They were brought by barge from Sittingbourne in Kent, where the clay and chalk substrata was ideal for manufacturing strong bricks. So many were required that it created a shortage of bricks and increased the price for other building projects in London at that time. Landmann also pioneered the use of concrete as a foundation. The River Ravensbourne was crossed at Deptford Creek by a balanced-bridge that allowed tall-masted ships to pass.

There were to be two parallel lines of Stephenson gauge, 4 feet and 8½ inches, fixed to stone blocks. Just three stations were initially planned, at Tooley Street, Deptford, and Greenwich.

Construction began in April 1834. Over 600 English and Irish navvies were employed in the construction and they were lodged at Southwark. As the two groups tended to fight each other the company had to separate their accommodation into what were called ‘Irish Grounds’ and ‘English Grounds’. The latter name still exists as a small street that runs parallel with Tooley Street.

An intention was to provide additional income by renting some of the viaduct’s arches as workshops, and others as homes. Two were completed as demonstration residences, but the noise of the overhead trains proved to be unpopular. Coal fires were forbidden because the smoke obscured the view of train drivers, and the arches leaked after heavy rain, so the idea was abandoned.

The width of the viaduct was 26 feet, with 22 feet reserved for the railway. There was a parapet of four feet in height. Along one side of the track the trains ran just eight inches from the side of the parapet, which was decided for safety reasons: the wall should keep the train upright if it ran off the tracks.

Tests of the railway began in June 1835. The first locomotives were built by Charles Tayleur & Company of Newton-le-Willows Lancashire, a company associated with the engineer Robert Stephenson. Others were manufactured by William Marshall of Gravesend. They were of the four-wheeled ‘Planet’ type that had been pioneered by the Robert Stephenson Company for the Liverpool & Manchester Railway. They tended to sway as they travelled and an additional axle was added to later locomotives. There were initially five locomotives: Royal William, Royal Adelaide, and three named after company directors. Experienced drivers were recruited from the Liverpool & Manchester Railway.

First- and second-class carriages were provided. Short iron bars connected the early carriages to each other, with only the end carriages having buffers. Each carriage had one door. Second-class carriages had seats around the sides of each car, and along the centre where passengers sat back to back. Across the end of the outside of each carriage were additional seats. The floors of the initial carriages were only 22 inches above the tracks. The wheel arches protruded into the carriages, which was inconvenient for passengers. The initial carriages, with their low floors, were replaced in 1844.

A test run on the section of track from Deptford to the Surrey Canal was made in October, pulling eight carriages with 256 passengers. A mile was covered in three and a half minutes.

There was then a great deal of excitement in the new concept of railways. Other companies were already building lines and the London & Greenwich Railway Company were anxious to be the first to carry passengers into London, maintaining the public’s interest, and thereby enhancing their share price. By February 1836 a section of the line from Spa Road at Bermondsey to the western bank of the River Ravensbourne at Deptford was complete, passing over marshes and market gardens. A temporary terminus was created at Spa Road, accessed by wooden stairs up the side of the viaduct, and services began to operate for the curious public.

It was thought that passengers could climb up into carriages from track level but low-level platforms were found to be more convenient. Services ran every hour on the half hour during daylight hours. The line wasn’t illuminated and there were no signals at that early stage, so it was too dangerous for trains to operate in the darkness. The fare was set at 6d (six pence), with £17 of tickets sold in the first week and £31 in the second week. On Whit Monday there were 13,000 passengers.

The stone blocks on which the rails were fixed proved to be too rigid for the rails, which broke and caused frequent derailments, reducing passenger numbers, and they had to be replaced by timber sleepers.

A gravel toll path, or ‘pedestrian boulevard’, initially ran parallel with the rail lines, saving a mile and a quarter and 25 minutes on the journey by road. There were no trains on Sundays but the path, which was later replaced by an additional track, remained open.