Lord Nelson and his Lasting Legacy in London Part 1

Note: This article was written in August 2011

Part 1. The funeral and the tomb

I am far from London, standing below a lighthouse on a naturally-formed sandbar that juts out to sea in the south of Spain. The strong winds coming in off the Atlantic, combined with hot temperatures and fine beaches make the area a Mecca for wind-surfers and kite-enthusiasts from all over Europe.

This point lies about equidistant between two of Europe’s most historic harbours. Just to the south is Tarifa, from where in previous centuries pirates demanded payment from ships passing between the Mediterranean and the Atlantic, most likely giving us the English word ‘tariff’. From there the mountains of the North African coast stand high, separated from Spain by what seems only the width of a large river. A short drive to the north is the harbour of Cadiz, Europe’s oldest continually-inhabited town, which was already ancient when the Romans came to occupy it and from where Christopher Columbus made some of his voyages to the New World.

This is Capo de Trafalgar, or Cape Trafalgar, and the momentous conflict that took place at sea, just out on the horizon, on 21st October 1805 gives its name to our most famous London square. Now a signboard in Spanish and English stands below the lighthouse and faces out to that point, giving some explanation of the battle but without mentioning winners and losers or the legacy that the day left other than the number of casualties.

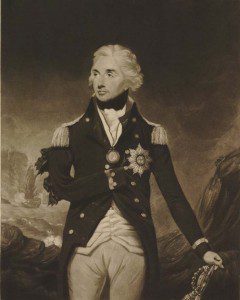

© The Trustees of the British Museum

Earlier this year we experienced in London the royal wedding of Prince William and Kate Myddleton and marveled at the vast crowds and huge interest in the event from around the world. Royal events such as coronations, marriages and funerals – and the restoration of the monarchy upon the return of Charles II in the 17th century – have long been of great popular interest, involving grand processions through the streets of the capital, accompanied by celebrations or bereavement around the country. What was remarkable about the funeral of Lord Nelson in 1806, and what made it unique at that time, was the sheer scale of the event and the public grief for a ‘mere’ commoner.

Nelson’s fame and reverence were due to not only his great naval victories – particularly at the Battles of the Nile and Trafalgar – but also the manner in which he achieved his success. He was not a leader who commanded from a safe distance, instead directing without heed to his personal safety. He earned great respect from those he commanded as well as the acclaim of the British people, although not necessarily amongst some in high command. On occasions he defied orders, such as the famous occasion during the assault on Copenhagen in 1801 when he put his telescope to his blind eye and was thus unable to see the command from Admiral Sir Hyde Parker to retreat from battle. His exploits cost him an eye, then an arm, and finally his life. It was not simply gung-ho exhibitionism: Nelson was a highly intelligent, yet unconventional, naval tactician of the highest order.

Norfolk-born Horatio Nelson spent his entire career in the navy, having joined as an ordinary seaman aboard a ship captained by his uncle at the age of twelve. His first experience of combat came at the age of seventeen and he was only twenty when he took his first command of a ship in the American War of Independence. During the French Revolutionary War he was involved in a great deal of action in the Mediterranean, losing the sight of his right eye attempting a landing at Corsica. He was in command during the capture of several Spanish ships during the Battle of Cape Vincent. That outstanding success brought him to the attention of the British public for the first time and earned him a knighthood. He was hit by gunfire during the unsuccessful attempt to capture the Spanish port of Santa Cruz de Tenerife, ordering the amputation of his right arm so that he could immediately return to battle. On his arrival back in England he was given a hero’s welcome and the Freedom of the City of London.

Prior to Trafalgar, Nelson’s greatest success came in the summer of 1798 when he led the destruction of the French fleet at the Battle of the Nile, leaving the French commander, Napoleon Bonaparte, stranded. When the news arrived back in England there were great celebrations, with church bells rung and public feasts. Nelson was fêted and elevated to Baron Nelson of the Nile. Later that year he was awarded the title ‘Duke of Bronté’ by the King of Naples and after the Battle of Copenhagen in 1801 he gained the rank of Viscount.