Saxons and Vikings: Before the Norman Conquest

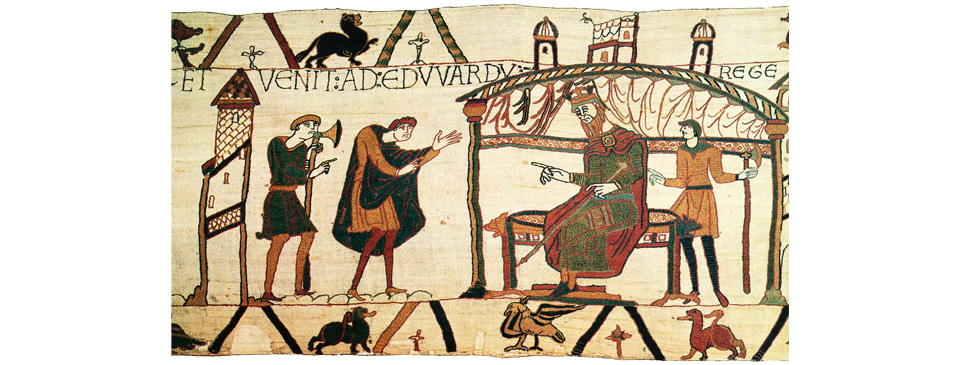

King Edward sits on his throne in the Palace of Westminster in this depiction from the Bayeux Tapestry. His decision to rebuild Cnut’s old palace and to create a magnificent new abbey transformed Westminster from a swampy island beside the Thames to a royal and religious place of national importance.

In 1016 Sweyn’s son Cnut returned to England, and at that time Aethelred died and was buried in St. Paul’s. Aethelred’s son, Edmund Ironside, continued the defence of the country and the councillors and citizens of London elected him as their new king. Edmund broke out of London, raised an army to fight Cnut in Essex and was defeated but not decisively so. An agreement was reached to divide the kingdom, with Edmund taking Wessex in the south-west, and Cnut Mercia in the Midlands down to and including London. Whichever of them lived longest would gain the other’s half. Edmund was assassinated later that year and the English crown passed to Cnut, thus uniting England and Denmark.

King Cnut ruled wisely and ensured a time of peace and prosperity during his reign. He united the Danes and Anglo-Saxons by marrying Emma, widow of Aethelred. Although he granted lands in England to his Danish followers he also kept the majority of the Anglo-Saxon nobility in place and continued with much of the previous governmental systems and laws.

Cnut, a Christian, built a palace beside the church that had originally been established by St. Dunstan’s monks on the island of Thorn Ea (Westminster), establishing the location’s existence as a place of royalty and religion that has continued into modern times. It was sometime around this period that the border and jurisdiction of London expanded westwards, beyond the wall, to somewhere around its present position at the Holborn and Temple Bars.

The famous legend concerning Cnut is that he proved to his fawning courtiers that he was unable to hold back the tide and, if this event is true, it may have taken place at Westminster. In the words of the 16th century historian John Norden: “He passed by the Thamys, which ran by that Pallace, at the flowing of the tide; and making staie neere the water, the waves cast forth some part of their water towards him. This Canutus conjured the waves by his regal commande to proceede no further. The Thamas, unacquainted with this new god, held on its course, flowing as of custome it used to do and refrained not to assayle him neere to the knees”.

Cnut’s empire eventually consisted of Denmark, England, Norway and parts of Sweden. He was a good diplomat, creating alliances with Rome and various European kings. With the Danes being skilled sailors many trade routes were created, stretching from Russia, through northern Europe as far west as Iceland and north America, and London was able to take advantage of that.

Danes settled in areas to the west of the city around Aldwych and lasting evidence of this is the existence of St. Clement Danes in the Strand, a church that was originally built of wood and rebuilt in stone in the time of Cnut. Others lived around Clapham, which derives its name from their leader Osgod Clapa, and at Hakon’s Ea (Hakon’s island, present-day Hackney).

Cnut created a standing navy. It became a political force in England and when the king died in 1035 the “men of the fleet in London” joined with others in the royal council to propose a succession to the crown. However, a war between Denmark and Norway at that time prevented the chosen successor, his son Hardicnut, from taking the English throne, which instead was seized by Hardicnut’s half-brother, Harold Harefoot. By the time Hardicnut arrived in England to claim his throne Harold had anyway died. He was buried in the abbey at Thorn Ea but his body was exhumed by Hardicnut and thrown in the Thames. It was recovered and reburied at St. Clement Danes.

When King Cnut’s son Hardicnut died during the wedding feast of Tofi the Proud, an eminent noble, at Lamb’s-hithe in 1042 – the first written record of Lambeth – there was no obvious Danish successor. According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle “all the people chose Edward as king, in London”. Thus, the surviving son of Aethelred – who became known as Edward the Confessor after his death – came to the throne and the Saxon lineage was resumed.

Edward spent much of his reign fighting his father-in-law, the powerful nobleman Earl Godwine, Earl of Wessex, based at Guildford. In 1051 Godwine and his sons were ordered before the ‘Witan’ – the king’s council – in London to answer charges against him. Godwine and his men camped at Southwark to bargain but the leading earls of England and the people of London remained loyal to Edward, and Godwine and his family, including Edward’s wife Queen Edith, were sent into exile. Despite being abroad, Godwine remained a strong influence and he began to gain support amongst influential Londoners. The following year he sailed up the Thames, passing through London Bridge to Southwark where a large number of his troops waited for him. Edward backed down and Godwine’s confiscated lands were returned.

After Godwine’s death in 1053 his son Harold became ‘under-king’. Edward moved a mile and a half west of London and had a fine new stone palace constructed at Thorn Ea, replacing Cnut’s earlier palace. While in residence there he could watch the progress of the construction of his vast new Westminster Abbey. The older royal Wardrobe Palace close to St. Paul’s was probably abandoned from then and, thus, the English monarchs forevermore left the City of London. It thereafter remained a place of commerce and in the following centuries Westminster was to become the centre of royalty and government.

Sources include: Christopher Brooke ‘London 800-1216’; R.G. Ellen ‘A London Steeplechase’; Sir Robert Cooke ‘The Palace of Westminster’; Hilary St. George Sanders ‘Westminster Hall’; Penelope Hunting ‘Royal Westminster’

< Back to Saxons, Vikings and Normans