St.Paul’s Cathedral during the Reformation

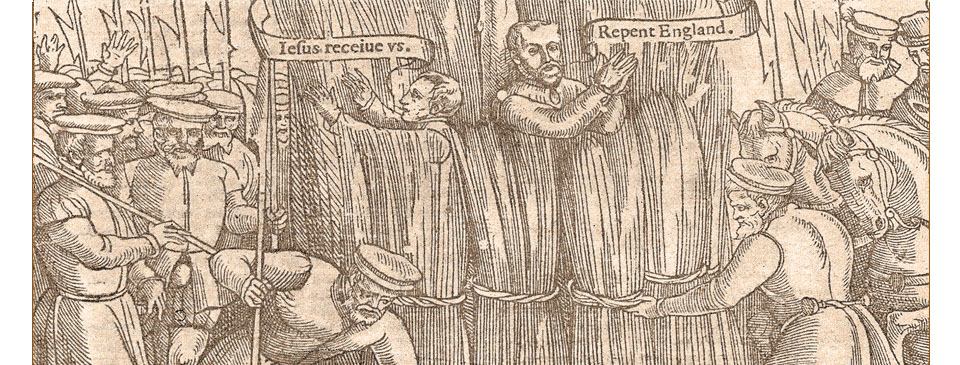

The preparations for the execution of Protestant Martyrs John Bradford, a prebendary of St. Paul’s, and the nineteen-year-old apprentice John Leafe. They were burnt at the stake at Smithfield on 1st July 1555 during the reign of ‘Bloody’ Mary. The illustration originally appeared in John Foxe’s ‘Book of Martyrs’, the first edition of which was published in 1563.

During the years of religious turmoil that led to the Reformation in England, Paul’s Cross in the churchyard of St. Paul’s Cathedral became a focus of national theological debate. Sermons were given by both those who sought reform and their conservative opponents. Like all other religious institutions in the country, the cathedral went through a long period of change.

In the first decades of the 16th century a challenge to the teachings of the Roman Catholic Church and papal supremacy spread across Europe. A key figure in the rejection of the orthodoxy was the German theologian Martin Luther. His ideas eventually led to a schism in European Christianity and the establishment of the Protestant movement. This process began with what is known as the Reformation.

In May 1521 Cardinal Wolsey, Lord Chancellor and the leading advisor to Henry VIII, together with the Pope’s representative, the Archbishop of Canterbury, bishops, ambassadors, and nobility rode in procession to St. Paul’s Cathedral. From a high platform in the churchyard an estimated 30,000 Londoners listened as they denounced Martin Luther, who had been excommunicated by the Pope and outlawed by the Holy Roman Emperor. John Fisher, Bishop of Rochester, gave a two-hour sermon, stating “The spirit of Christ is not in Martin Luther” and that the King, Henry VIII, had condemned Luther in his manuscript Assertio Septem Sacramentorum. A papal bull against Luther was posted on the door of the cathedral. But by the next morning an unknown hand had scrawled a message – “Bulla bullae ambae amicullae” and “Araine ante tubam” – above each of the two pages of the document, mocking the Pope. The cardinal was outraged. A decade someone fixed a broadsheet to the cathedral doors attacking the veneration of saints, fasting, and pilgrimage.

As the Reformation was gathering pace on the Continent, Henry VIII had his own, quite different, quarrel with the Pope. In the early part of his reign Henry VIII was a dedicated supporter of the Catholic doctrine. However, the Pope’s refusal to accept the annulment of his marriage to Catherine of Aragon led in 1534 to him declaring himself head of the Church in England, separate from Rome. Across the whole of Europe the Catholic Church had over many centuries become immensely wealthy. Declaring himself head of the Church allowed Henry to seize its vast assets, and to extinguish the only body powerful enough to question his will.

In London thousands of women rioted in 1531 and unsuccessfully attempted to seize Henry’s future wife, Anne Boleyn. The following year a woman interrupted a sermon at St. Paul’s in favour of the divorce, crying: “[it] would be the destruction of the laws of matrimony”.

St. Paul’s Cathedral had lacked a strong, leadership for a generation. Unlike many other ecclesiastic institutions, in 1534 the canons and priests of St. Paul’s acknowledged Henry as head of the Church in England. From 1535 the cathedral functioned under the auspices of the Royal Supremacy, in the person of Thomas Cromwell, the King’s vice-gerent, a proponent of religious reform. That October Cromwell granted the cathedral a licence to continue spiritual jurisdiction. The Bishop of London, John Stokesley, maintained his conservative preaching, however, so Cromwell instead licenced the more compliant Bishop of Rochester to appoint preachers at Paul’s Cross. In 1536 Archbishop Thomas Cranmer and Bishop Hugh Latimer gave sermons denouncing the Pope and affirming the royal supremacy.

The transition from Catholic worship to what became the Anglican tradition gradually evolved over several decades and with great debate and fluctuation, causing much confusion and uncertainty during the latter years of King Henry. It would take many years before the old ways were completely abandoned by the people.

In the spirit of reform, in October 1535 a holy relic of Our Lady’s milk, that was being used “in deceiving people”, was taken from the cathedral and in 1538 Dean Richard Sampson removed various pilgrimage attractions. Yet the pace of reform in the country was too great for Henry. In November 1538 a proclamation was issued ordering any Anabaptists, the radical puritan movement, to leave the country. Several weeks later over 20 Dutch Anabaptists were rounded up and sent for trial at St. Paul’s Cathedral. Having been found guilty of doctrinal heresy they were sentenced to be burnt at the stake. In June 1539 Henry issued the Act of Six Articles that reaffirmed the ‘old religion’. Cromwell’s political enemies and those against religious reform plotted against him and he was executed in July 1540.

Within St. Paul’s the forces of reform and conservatism pulled in opposite directions. Bishop Stokesley died in September 1530 and was given a magnificent Catholic funeral in the cathedral. He was buried behind the shrine to St. Erkenwald. At his death, according to the Tudor historian John Foxe, Stokesley boasted “that he had sent 31 heretics unto the eternal fire”. But the shrine of Erkenwald, patron saint of London, which had been located in St. Paul’s since the 7th century, was demolished during 1540-1 and his relics disappeared. Edmund Bonner, Stokesley’s successor, supported Henry’s claim as head of the church but was a conservative in many of his actions. To the dismay of reformers he installed new images to replace those previously discarded.

Henry died at Whitehall Palace in January 1547 and was succeeded by his nine-year-old son. On the day before his coronation Edward went in procession from Westminster Abbey to St. Paul’s. There he witnessed a high-wire artist slide down a cable stretching from the cathedral’s steeple to the deanery.

Edward VI had been educated by evangelical custodians according to the Protestant theology. His guardians quickly gained the upper hand over the orthodox conservatives. Reformists in exile returned to England, as well as refugees from persecution. In September images were removed from St. Paul’s and the Epistle and Gospel began to be read in English during mass. In November the revered rood (or crucifix) at the north door was taken down, the work undertaken during the night to prevent riots. At least one workman was killed and others injured during the process, which was a sign from God of His displeasure according to papists. During 1548, under Dean William May, Catholic practices were discontinued and various new forms of Protestant worship introduced, with readings from the Holy Scripture given four times each week.

At the same time, various changes were made to the organisation of the cathedral and its community. Most colleges, chantries and fraternities were dissolved. The charnel house and its chapel were leased out to booksellers and the bones of those buried there transferred by cart and dispersed outside the city wall at Moorfields and Finsbury. In 1549 Protector Somerset, the young King’s guardian, ordered the demolition of the Pardon churchyard cloister, where the parents of St. Thomas had been buried, as had many of London’s leading citizens. He used the stonework, including tombs, in the building of his Somerset Palace, the predecessor of the current Somerset House on the Strand.

Revolts against the religious changes broke out in various parts of the country and in July Cranmer gave a sermon at St. Paul’s to denounce them. Despite his early compliance, Bishop Bonner continued to allow Catholic worship in the cathedral, resenting the reforms carried out Dean May. Following his failure to prohibit such practices he was put on trial and committed to Marshalsea gaol in September 1549.

Bonner was succeeded by Nicholas Ridley in 1550 – uniquely as Bishop of London and Westminster – and the pace of change increased. The cathedral’s high altar was demolished overnight in June that year, although it provoked a fight and a man was killed. The use of the organ was discontinued in 1552, and subsidiary altars demolished. Ridley himself officiated at the introduction of the revised, evangelical Book of Common Prayer in November of that year. In May 1553 all religious items no longer used in the new doctrine were removed from the building on the orders of the government.

Yet the wind was about to change. The young King Edward’s Protector, the Duke of Somerset, was imprisoned in October 1549, giving conservatives false hope of returning to the old religion. That was not to be for a few more years, until the young Edward died in July 1553. In a sermon from Paul’s Cross Bishop Ridley declared to Londoners that Henry VIII’s daughters, Mary and Elizabeth, were debarred from the succession by their illegitimacy. But that was not a view universally shared by the congregation, many of whom resented the religious reforms. Several days later in Cheapside the Catholic Mary was proclaimed the rightful queen. The mayor then led a procession into St. Paul’s, where the choir sang a solemn Te Deum and the organ was played once again. Mary arrived in London on 3rd August and Bonner was released from Marshalsea, going directly to the cathedral to pray on the steps.

Catholic practice was reintroduced during the following weeks. The high altar was rapidly rebuilt in the cathedral, but in too much haste because it collapsed on the first attempt and had to be restarted. A ceremonial procession passed through the cathedral’s precinct in September on the eve of Mary’s coronation. Bishop Ridley, who had opposed the succession of Mary, was arrested and sent to the Tower of London, and Dean May and all the married clergy replaced. Now it was the turn of Catholic exiles to return to the country. Feast days were once again remembered, including that of St. Erkenwald in November. Processions took place again, with that of St. Katharine around the cathedral’s steeple in the same month.

Mary planned to marry Prince Philip of Spain to produce a Catholic heir. An uprising led by Thomas Wyatt against Mary’s wish was successfully put down and some of the participants hanged in the cathedral churchyard in February 1554.

In December 1554 a public ceremony in commemoration of papal supremacy was held at St. Paul’s, attended by Cardinal Pole, Bishop of London Bonner, the Bishop of Winchester, and the mayor and aldermen of London. Mary’s new husband Philip arrived with a guard of 400. A crowd of 15,000 gathered outside at Paul’s Cross for a sermon confirming the restoration of papal supremacy.

Cardinal Pole issued instructions for the arrest of those accused of heresy, many of the trials taking place in the Consistency Court of St. Paul’s. One hundred and thirteen were condemned to death by Bishop Bonner. The first of almost 300 ‘Protestant Martyrs’ to be executed during the reign of ‘Bloody Mary’, between February 1555 and November 1558, was John Rogers, a clergyman and lecturer of St. Paul’s, who was burnt at the stake at Smithfield in February 1555. Several months later the same fate befell another of the cathedral’s clergymen, John Bradford. Bishop Ridley was sent for trial in Oxford and burnt at the stake there in October 1555, along with Hugh Latimer, Bishop of Worcester. Archbishop of Canterbury Thomas Cranmer perished the following year. Those executed in November 1558 were particularly unfortunate because Mary died that month during an influenza epidemic, on the same day as Cardinal Pole, the last Catholic Archbishop of Canterbury. Queen Elizabeth then ascended the throne and England’s religious clocks were turned back to the time of Edward VI.

Sources include: Various – ‘St. Paul’s – The Cathedral Church of London’; Susan Brigden ‘London and the Reformation’; ‘Luther’s Correspondence and Other Contemporary Letters: Vol. 2 1521-1530’, ed. Preserved Smith and Charles M. Jacobs.

< Back to St. Paul’s Cathedral during the early Middle Ages

Forward to St. Paul’s Cathedral during the reign of Elizabeth I >