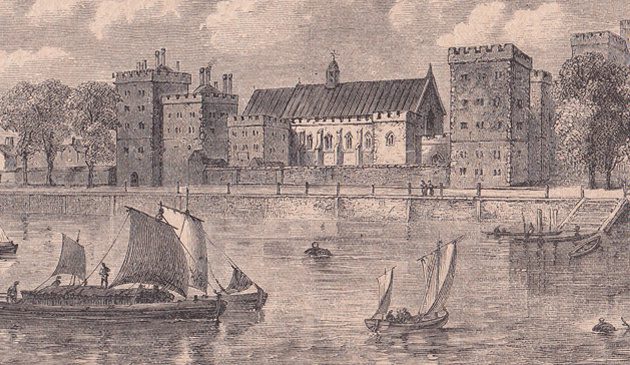

St.Paul’s Cathedral in the early Middle Ages

The shrine of St. Erkenwald at St. Paul’s Cathedral. By the time this engraving was made by Wenceslaus Hollar in the early 17th century Erkenwald’s body had long disappeared. The shrine itself was destroyed in the Great Fire later that same century.

The traditional Romanesque-style St. Paul’s Cathedral of the Middle Ages was once one of the largest buildings in Europe, towering high above everything else in London. Its construction created the pre-metric length of a ‘foot’. While Westminster Abbey continued as the principle church of English royalty, St. Paul’s became the stage for national events.

At the very start of the 7th century Augustine ordained Mellitus as Bishop of the East Saxons. In the year 604 St. Paul’s, at the top of Ludgate Hill in London, was founded as Mellitus’s cathedral, with the episcopal see being the area north of the Thames extending to, approximately, the modern-day Essex, Middlesex and Hertfordshire. From 693 the cathedral contained the tomb of Erkenwald, an early Bishop of London and Essex and the first saint to be buried in the city. The original cathedral building was no doubt a relatively small and simple structure that stood until 962 when it was destroyed by fire and rebuilt.

In 1087 there was another fire that destroyed much of London, including St. Paul’s, and the Normans replaced the second cathedral on the same site but on a much grander scale. The size of the new cathedral was so great that it took over 130 years to complete. Work began in the late 11th century under the direction of Bishop Maurice and it was finally finished in the 1320s. Even as construction work was taking place, a major fire in the 1130s caused much damage.

The Norman building was designed in the Romanesque style, constructed at least in part from stone quarried at Caen in Normandy and Taynton in Oxfordshire. Along the way it rose higher and grew larger, rising early on above the level of the city walls and all London’s other properties. In around 1175 the main building was complete, by which time it dwarfed all other structures in the city and could be seen from miles around. It was by then larger than England’s other great cathedrals of the period such as Bury St. Edmunds, Ely, Peterborough and Rochester. The only larger building in the whole of Europe at that time was its contemporary, Winchester Cathedral, which was started eight years earlier.

The first section to be completed was the choir at the east end of the cathedral, with a rounded apse. Below it was the crypt, with painted vaults. The transepts that gave the building its cross-shape, projecting north and south of the central crossing, were each five bays long, with chapels on the east sides, perhaps a later addition, and aisles on their west sides. They contained a number of altars and the ‘miraculous’ Crux borealis – a rood, or crucifix that was to be much revered over the following centuries – by the north transept door. The treasury, where the liturgical robes and precious objects were kept, was located along the south side of the choir, entered through the first bay of the south transept.

The nave, twelve bays in length, with aisles on each side below galleries, was under construction during the time of Maurice’s successor, Bishop Richard de Belmeis the elder, in the second and third decades of the 12th century. A rib-vaulted ceiling above the nave was constructed in the latter 12th century. The west façade included a triple portal, with low flanking towers to the north and south that were used as prisons. A residence for the bishops was built adjoining the north-west corner of the main building.

The impressive tower and spire above the central crossing were completed in about 1220, dominating the surrounding city and countryside. The tower stood about 260 feet above the crossing floor and the spire above that 274 feet high, with a total height together of almost 500 feet, or 152 metres, 30 metres taller than the present dome. Unstable from the beginning, the tower required buttresses to keep it in place. A chapter house was added in the angle between the nave and southern transept sometime prior to 1240. Despite the cathedral’s dedication in 1241 work was still continuing.

During its construction a particular length was noted as being 57 feet by the foot of Canon Algar. In order to ensure its standardisation the measurement was carved into a pier-base in the nave and for at least several centuries was known as the ‘foot of St. Paul’. The phrase went out of use after the 15th century and the column destroyed, most likely in the Great Fire of 1666, but a foot continued as part of imperial measurements into modern times.