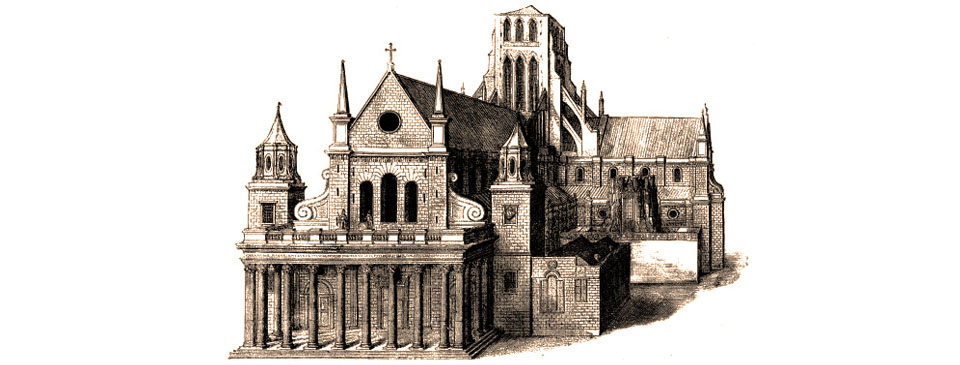

St. Paul’s Cathedral in the early Stuart period

The old St. Paul’s from the west showing the Italianate portico designed by Inigo Jones. It was added to the west front as part of the extensive refurbishment of the building in the 1630s. The print was made as part of a series by Wenceslaus Hollar as a commission to illustrate William Dugdale’s History of St. Paul’s, published in 1658.

Bishop Laud and Dean Overall were out of step with the changing religious views of many of the people of London, which was becoming increasingly Puritan. Laud was part of a group of Protestants known as ‘Arminians’ after the Dutch professor Jacob Arminius, who held certain theological views that were at odds with the majority of people in the country, particularly Calvinists. In 1633 Laud was appointed as Archbishop of Canterbury and succeeded as Bishop of London by William Juxon. Decrees that Laud issued to restore uniformity of worship made him increasingly unpopular and endorsement given to him by the King lost Charles support in the country. Religious demands made by Laud on Scotland’s Presbyterians resulted in a Scottish army marching south and occupying the north of England.

Such was the hostility towards Laud that in May 1640 hundreds of London’s apprentices marched on his London home at Lambeth Palace, intent on destroying it. Laud was forced to flee under armed guard to Whitehall Palace. There were riots at the cathedral in October, with the altar smashed. Clergy had to be protected by horsemen and musketeers. As Charles lost control of power, Parliament had Laud imprisoned in the Tower in 1641 and he was beheaded on Tower Hill in 1645.

The increasingly Puritan (or ‘godly’) Parliament was in conflict with the King over a number of issues. In April 1641 the Scots offered the Westminster Parliament their military support, provided that the Church of England conformed with the Presbyterian Church of Scotland. In September godly extremists entered St. Paul’s during a service and forced the altar and rails to be taken away. King Charles fled London in early 1642 and for the following 18 years the city came under the control of the Puritan-dominated Parliamentarians.

London’s parish churches were purged of Anglican clergy and of anything considered Laudian or popish. The pulpit of Paul’s Cross was demolished sometime around 1641 and in November 1642 the cathedral itself was closed for worship. The following January the Anglican Church was abolished. Parliament replaced the dean and chapter of St. Paul’s with a committee. The cathedral’s gold, brass and ornaments were sold and the restoration fund confiscated. Many valuable items simply went missing. The deanery was converted into a prison in 1643. The mighty organ was destroyed by order of a parliament committee in 1644. In 1649 Inigo Jones’s statues of King James and King Charles above the west portico were destroyed. Senior clergy, and probably most others, were deprived of their posts and income, and some were imprisoned for their continued resistance to the changes. Bishop Juxon spent the next decade living quietly on his estate in Gloucestershire.

In December 1643 Parliament appointed the fiery preacher Cornelius Burgess as public lecturer and in April 1645 he was appointed as lecturer of St. Paul’s. The former deanery was restored as his living quarters. He remained in place for several years until the ongoing turbulence in London made him decide to move elsewhere.

There followed a period of continuous political, cultural and religious debate, division and militancy. In 1647 London was occupied by the New Model Army and the nave of St. Paul’s requisitioned as a barracks and stables. The soldiers were forced to sleep on the cold stone floor and nearly destroyed the building by burning fires, made by tearing out the pews, choir and scaffolding, until the Mayor provided them with coal. In January 1654, with the scaffolding and timber props removed, part of the cathedral’s roof collapsed, and several people were killed. The churchyard was sold to a building speculator who created a shanty town of housing against the cathedral walls, and shopkeepers set up stalls under the portico.

The republican regime lurched from one crisis to another and by 1657 was convinced that the exiled Charles II was about to invade. Oliver Cromwell ordered that 600 army horses be once again stabled in the cathedral in readiness.

Cromwell died in September 1658 and the republican commonwealth neared its end. The following February General Monck marched his army from Scotland in order to restore order to London. On arrival he accompanied the Mayor at a service at St. Paul’s. Charles II arrived in London at the beginning of May 1660 and later that month was presented with a sumptuous bible in a ceremony outside the cathedral. The Anglican Church of England was restored as the official form of worship. Bishop Juxon returned from retirement and quickly appointed men into the vacant posts at St. Paul’s, many of whom had served prior to the interregnum. In September Charles named him as the new Archbishop of Canterbury and he was succeeded as Bishop of London by Gilbert Sheldon.

Not everyone in London was happy with the Restoration and return to Anglican worship. The Fifth Monarchists were a group of religious fanatics, a sect that believed Christ would return to succeed the Assyrians, Persians, Grecians, and Romans. To them there was no king but Christ and Charles was a usurper who contradicted their beliefs and expectations. In January 1661 about 60 of them marched forth through the City, fully armed, crying that they went for King Jesus. They briefly occupied St. Paul’s and killed a man in the churchyard who cried out for King Charles. The Mayor quickly raised a company of trained bands but they were insufficient in numbers to overpower the rebels. Meeting further resistance Fifth Monarchists headed out of the City. After several days some were killed during gunfights, and others captured and hanged, drawn and quartered. Parliament called for a crack-down on non-conformists, made into law as the ‘Clarendon Code’.

Much damage had been done to St Paul’s during the interregnum. Sheldon’s priority at St. Paul’s was the re-establishment of the choir in the eastern end of the cathedral so worship could continue. A makeshift arrangement was put in place, separated from the remainder of the building by a temporary wall, until repairs to the rest of the building could be undertaken.

In April 1663 a Royal Commission was appointed by Charles II to organise a full survey, make decisions on repairs, and consider methods of funding. In July Sir John Denham, the Surveyor-General, recommended demolition of the tower and extensive changes to the crossing. Scaffolding had already arrived from Norway the previous month for work to begin. But the commissioners first wished to seek further advice. The lawyer and gentleman architect Roger Pratt, then working on a grand new house at Piccadilly for the Earl of Clarendon, recommended minor repairs. In contrast, in May 1666 the mathematician and astronomer Dr. Christopher Wren, recently returned from nine months studying architecture in France, submitted a report to the commissioners proposing a major rebuilding, including replacing the tower with a dome.

A meeting consisting of the Bishop of London, the Dean of St. Paul’s, Hugh May (Charles’s Paymaster of the Works), Pratt, Wren, and three independent advisors, including John Evelyn, met at the cathedral at the end of August 1666 to settle the issue. These matters became irrelevant, however, when just a few days later the building was all but destroyed in the Great Fire of London.

Sources include: Various – ‘St. Paul’s – The Cathedral Church of London’; Adrian Tinniswood ‘By Permission of Heaven’; Michael Cooper ‘Robert Hooke’; Sir Walter Besant ‘London in the Time of the Stuarts’ (1903); Illustration courtesy of the collection of Hawk Norton.

< Forward to The Rebuilding of St. Paul’s Cathedral after the Great Fire of London