The westward growth of London in the 17th century

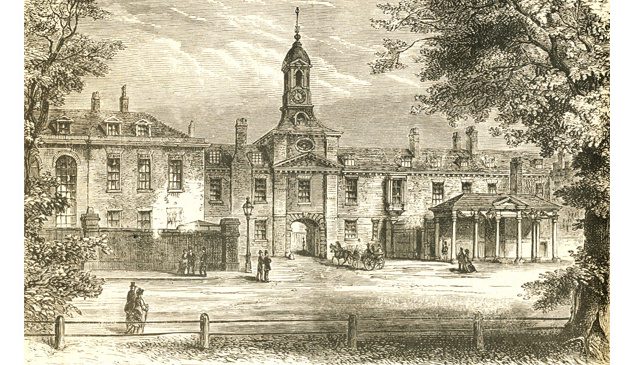

A 19th century artist’s impression of the Lord Chancellor’s grand mansion Clarendon House on Piccadilly, facing towards St.James’s Palace, in the 1660s. Despite its huge cost it stood for less than twenty years before making way for the new development of Bond Street and Albermarle Street.

The creation of the suburb of Covent Garden in the early 17th century started a trend of fashionable housing for aristocrats and the wealthy on the west side of London. Development was interrupted by the Civil War but began apace following the Restoration of 1660.

Until the Great Fire, the old City of London, contained within its walls, remained as it had evolved since Saxon times. Many houses, taverns and workshops were built of wood and plaster in Tudor style. Most churches and civic buildings were of stone, originally constructed during the medieval period. Streets led this way and that and buildings jutted out in irregular fashion with little uniformity in their planning.

It was the ambition of Charles I to build magnificent new palaces and buildings for London similar to those being created in Paris during the first half of the 17th century but he lacked the funds to initiate any grand schemes. His great contribution to the topography of London was to agree to the development of Covent Garden by the Earl of Bedford, designed by the Royal Surveyor Inigo Jones. Two other smaller schemes followed nearby in the 1640s that strengthened the influence of the Jonesian style in London, that of Lindsey House on the west side of Lincoln’s Inn Fields and the south side of Queen Charlotte Street between Lincoln’s Inn Fields and Long Acre. From then on there was little development of any note in or around London in the decade of Civil War and Commonwealth. During that time almost all building on a large scale took place at the country estates of aristocrats.

Bedford had planned Covent Garden with its piazza in the 1630s but many of the type of aristocrats and gentry he had in mind to rent properties moved away from London into exile or to lie low in the countryside at the start of the Civil War in 1642. From the time of the Restoration in 1660 they were back in force, many owning country estates but also with the requirement for a family-sized pied-á-terre in the capital. It stimulated a new housing boom and transformed the area to the west of the old City. These fashionable suburbs were convenient for those aristocrats wishing to be close to the royal palaces of Whitehall and St.James’s, those connected to Parliament at Westminster, or for the professional classes with business at the Inns of Court around the Strand. They were away from the narrow and congested City, having street widths planned with carriages in mind. Also they were up-river and – on more days than not – up-wind of the smoky and smelly industrial areas that the polluted Thames flowed past. Importantly for those who lived there they were a sign of their social standing.

A division had grown within London, with the wealthy aristocratic, professional and merchant classes generally having their homes in the west; and the poorer working classes in the north, east, and at Southwark. There were exceptions in both cases.

In 1659 the carpenter and property developer Abraham Arlidge started a new scheme north of Holborn on what had formerly been the grounds of Sir Christopher Hatton’s Hatton House, which eventually numbered almost four hundred houses. Hatton Garden was designed for merchants who wanted to live in the quieter suburbs and near the surrounding fields but still close to the City. It took almost forty years to complete.

The manor of Blemonsbury to the north of Holborn was acquired in 1545 by the then Chancellor, Thomas Wriothesley, and was used for orchards and market gardens. At around the same time as the Earl of Bedford was creating Covent Garden in the 1630s, his descendent, Thomas Wriothesley, 4th Earl of Southampton, considered creating a new mansion on the land – by then called Bloomsbury – to replace his Southampton House in Holborn, as well as laying out a square surrounded by housing. Charles was agreeable to the scheme and work started on the new house but the King failed to issue a licence for the entire development before the outbreak of the Civil War. The mansion was finally completed in 1661 and the idea of the square was then resurrected.

Rather than speculate his own money on erecting and selling properties, Southampton granted leases to builders who then had to take on the risk of construction and sub-leasing (or selling the leases) on the houses. At the end of the lease, usually forty two years, the houses became the property of Wriothesley. This system evolved in the following years, with longer leases being given, up to ninety nine years, but with an annual ground rent being charged by the landowner. Bloomsbury Square and the streets to its west evolved as part of that development. It soon became a fashionable place to live, with its houses around the central garden, creating a trend that established many squares in London during the following century.