The Clapham Sect and the campaign to end the slave trade

During the latter part of the 18th century a small group of people formed bonds of friendship. They set out to change Britain and the wider world with their evangelical Protestant ideas. Clapham, a village to the south of London, became the centre of their activities, giving them the name ‘the Clapham Sect’. Their greatest contribution to change was the end of slavery in the British colonies.

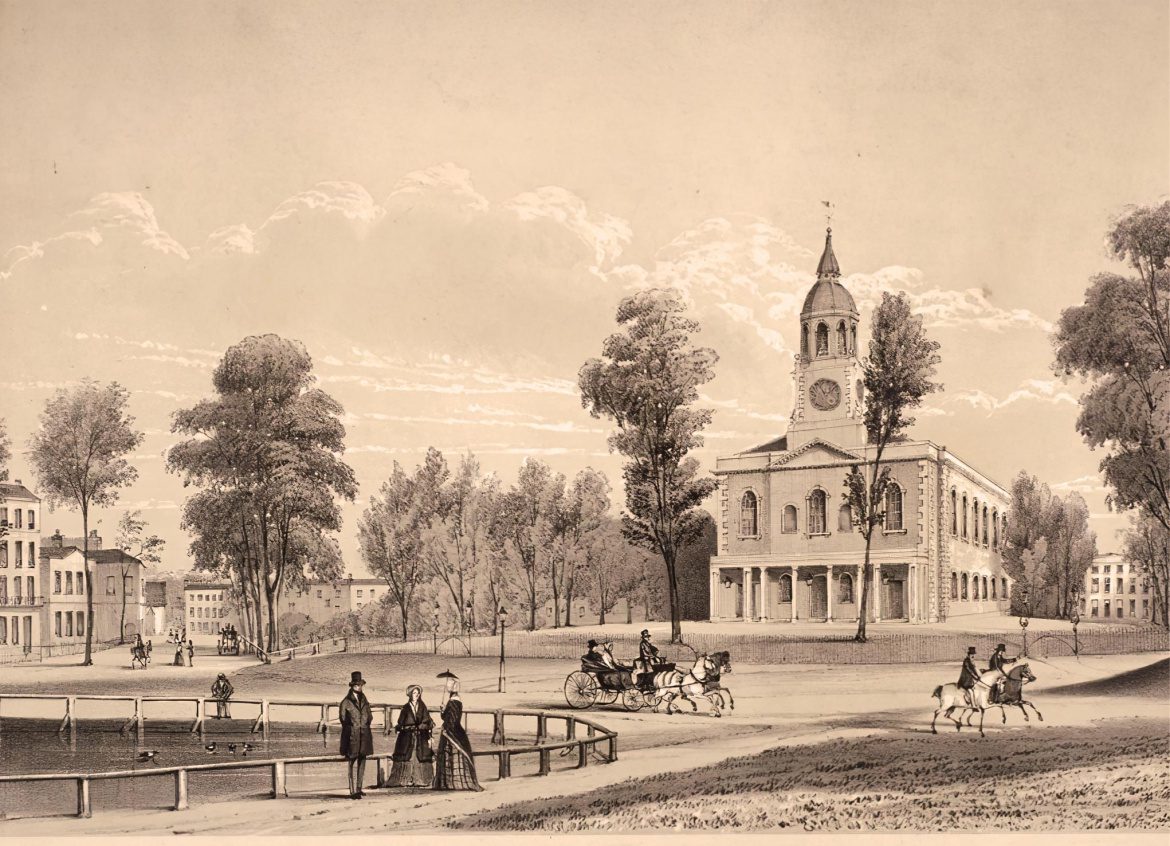

As the population of Clapham grew, the new Holy Trinity church was opened, away from the centre of the village, at a place where it would be more convenient for the wealthy residents living around Clapham Common. The sermons of its rector, John Venn, ensured that it became the centre of a group of like-minded Evangelists.

In the mid-18th century there was a revival of evangelical Protestant Christianity, similar to the Dissenters of a century earlier. Shunned by the official Church of England, evangelical preachers such as John Wesley and George Whitefield toured the country preaching to large crowds. Evangelicals believed that real Christians should lead radically holy lives. Many were zealously committed to social action, believing God wished the world to be improved. Some wealthy proponents used their money to found schools, medical dispensaries, and orphanages.

One such evangelist was Henry Venn, who was ordained as a minister in 1747 and in the following years served at churches in London and elsewhere. In 1754 he arrived at the old church in the village of Clapham, as curate to the absentee rector. Clapham was then a village four miles south-west of Westminster but its access to Westminster and the City made it a popular location for country homes of well-to-do merchants, particularly with the opening of new bridges across the Thames. Henry’s preaching was considered too extreme by the wealthy residents of Clapham, however, and he was forced to move to a living in the industrial town of Huddersfield where he found the parishioners to be more accepting of his sermons. Indeed, Venn’s preaching at Huddersfield made him influential in the evangelical movement throughout the country.

Yet at Clapham Venn had been influential in the conversion to evangelism of the businessman John Thornton. His parents were from Hull, having had made their money trading with Russia and the Baltic, but had moved to Clapham before John was born in 1720. John, who kept an office in the City, made a fortune lending to the government to finance the Seven Years’ War, becoming what was said to be the richest businessman in England. He used his wealth in part to expand the Clapham property into an estate large enough to keep deer. From the 1750s he became a major philanthropist, giving away huge sums each year to fund religious and charitable work.

A trust was formed, with Thornton as treasurer, to build a new church at Clapham to replace the old parish church. The new Holy Trinity church, a large, plain building, opened in 1776 on open ground a short distance away from the centre of Clapham village. Holy Trinity still remains a major feature of Clapham Common.

Amongst other things, John Thornton bought advowsons, the right to appoint a minister to a parish. One such appointment was that of John Newton. He had spent several years as a slave ship captain but had turned to Christianity and written an autobiography. After reading Newton’s life story, in 1764 Lord Dartmouth appointed Newton to the parish of Olney in Buckinghamshire. While at Olney he came to the attention of John Thornton who suggested he write a hymn book together with Newton’s friend, the poet William Cowper. It included the hymn Amazing Grace, with Newton perhaps thinking back to his time as a slave-trader:

Amazing grace!

How sweet the sound

That saved a wretch like me.

I once was lost, but now am found,

Was blind, but now I see.

In 1780 Thornton appointed Newton to St. Mary Woolnoth church in the heart of the City of London where he became a highly influential evangelical minister.

All four of John Thornton’s sons became Members of Parliament. In 1782 Henry Thornton, at the age of 22, was elected as MP for Southwark. He also went into banking in the City, rising to be a partner in an established firm and becoming one of the leading and most able bankers and economists of his time.

Henry Thornton’s cousin William Wilberforce was also born into a trading dynasty in Hull, but after his father died was sent to live with his aunt at Wimbledon. After graduation at Cambridge William decided on a career in politics and in 1780 was elected as an MP for his native Hull. Both Wilberforce and Henry Thornton sat as independent MPs so they would not be under the influence of powerful politicians. Wilberforce’s house at Wimbledon became a country retreat for political friends, one of whom was William Pitt the Younger, who in 1783 became Prime Minister.

It was while holidaying in France in 1784 with his former teacher Isaac Milner, a brilliant scientist, that Wilberforce was converted to evangelism. Thereafter he often met with John Newton. Happy with the news of his conversion, John Thornton and his wife offered William a room at their home at Clapham, much closer to Westminster.

Wilberforce, together with Henry Thornton and Edward Eliot, brother-in-law and collaborator to William Pitt, attended church at the Lock Hospital chapel in London where the celebrated Bible commentator Thomas Scott was the chaplain. The trio of friends, Wilberforce, Henry Thornton and Edward Eliot, became determined to use their wealth and influence to improve the country, by alleviating poverty, improving morality, and reforming and reviving religion.

The first project in which Wilberforce and Thornton became involved was the establishment of Sunday schools, where working-class children could be taught to read and behave. In 1785 they became founder members of the Society for the Encouragement of Sunday Schools, led by the Baptist William Fox. It was chaired by the Marquis of Salisbury and its directors included the bankers David Barclay and Thomas Coutts. It was incredibly successful, and by the middle of the 19th century around three quarters of all working-class children were part of a Sunday school.

Convicts sentenced to be transported for their crime had previously been sent to America but those colonies had recently been lost to Britain. At about that same time, however, James Cook had staked a claim to New South Wales on the eastern side of the Australian continent. In 1786 the first fleet of convict ships was sent there to create a colony. On board one of the ships was Richard Johnson, an evangelical minister, together with 1,200 Bibles, arranged by Wilberforce and Thornton.

During the second half of the 18th century there was a general disintegration of social order, as Britain’s population rapidly increased and people moved from the countryside to industrial towns. There was as yet no organised police force in Britain to enforce laws, combat crime, and guard against disorderly activity. Inspired by Joseph Woodward’s book The History of the Society for the Reformation of Manners in 1692, Wilberforce began a campaign to improve the morality of British life. With the help of Queen Charlotte and the Archbishop of Canterbury, King George III was in 1787 persuaded to issue a proclamation against disorderly behaviour. Wilberforce toured the country proposing to lords and bishops the formation of a new society. The Society for Carrying into Effect his Majesty’s Proclamation against Vice and Immorality, or Proclamation Society, was duly founded. The campaign was helped by the influential writing of Hannah More, a friend of Wilberforce, Samuel Johnson, and the actor David Garrick and his wife Eva.

Britain was a leading European nation in the slave trade. It had entered the business following the introduction of sugar production in its colonies of the West Indies in the mid-17th century. A century later 40,000 African captives were being shipped across the Atlantic each year. As the 18th century progressed there was a relatively limited but increasing disapproval of slavery in the British colonies and mainland America. The leading group calling for its abolition were the Quakers in both North America and Britain. A leading opponent of slavery was Granville Sharp. He took up the cause after helping the slave Jonathan Strong, who had been brought to London by his master, badly beaten and turned out onto the streets.

In the mid-18th century the naval ship HMS Arundel, captained by Charles Middleton, guarded British merchant ships in the West Indies. By 1786 Middleton was an MP and urged Wilberforce to take up the issue of slavey in the colonies. Wilberforce discussed it with Prime Minister William Pitt, who encouraged him to give notice of a parliamentary motion on the slave trade. A group of campaigners came together including Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson who had recently published an essay on the subject, James Ramsay, a minister who had witnessed the horrors of the trade first hand, freed slave Olaudah Equiano, and Wilberforce. The Society for Effecting the Abolition of the Slave Trade was formed. Clarkson toured the country gathering evidence and arousing popular support, while Wilberforce recruited from the upper classes.

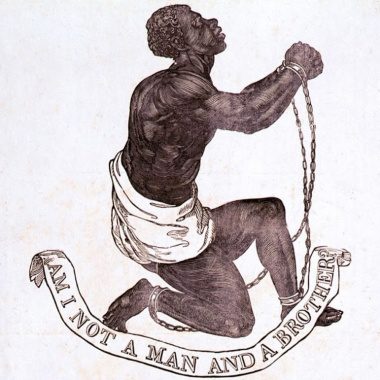

From the start, the group considered the abolition of slavery was too great an ambition, so their goal should be the abolition of the slave trade. After all, surely if the trade in slaves ended it should follow that slavery itself would eventually be extinguished. The potter Josiah Wedgwood, a committed abolitionist, designed the campaign’s emblem of a chained African with the slogan ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’. The former slave Ottabah Cugoano published his memoirs; John Newton wrote Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade; and Hannah More published Slavery: A Poem and persuaded Richard Brinsley Sheridan to stage the slave tragedy Orookoko. Parliament was deluged with petitions and Pitt initiated a Privy Council committee to consider the arguments.

From the start, the group considered the abolition of slavery was too great an ambition, so their goal should be the abolition of the slave trade. After all, surely if the trade in slaves ended it should follow that slavery itself would eventually be extinguished. The potter Josiah Wedgwood, a committed abolitionist, designed the campaign’s emblem of a chained African with the slogan ‘Am I Not a Man and a Brother?’. The former slave Ottabah Cugoano published his memoirs; John Newton wrote Thoughts Upon the African Slave Trade; and Hannah More published Slavery: A Poem and persuaded Richard Brinsley Sheridan to stage the slave tragedy Orookoko. Parliament was deluged with petitions and Pitt initiated a Privy Council committee to consider the arguments.

In 1789 the group of abolitionists was joined by James Stephen, a barrister from the slave-plantation island of St. Kitts who briefly met Wilberforce while on a visit to London. In Barbados Stephen had witnessed a trial in which two slaves were sentenced to be burnt to death for a murder that was almost certainly committed by a white man. He became the legal adviser to the group, and in 1797 moved to Clapham where he married Wilberforce’s widowed sister.

At about the time Stephen and Wilberforce first met, the MP Sir William Dolben was shocked when inspecting a slave ship on the Thames and he brought forward a Bill to alleviate overcrowding on slaving vessels. The Bill narrowly succeeded against much opposition and the Slave Trade Act 1788 passed into law, limiting the numbers of slaves carried on individual ships.

Wilberforce brought a motion to Parliament to abolish the slave trade in May 1789 to a rapturous reception. Yet those who profited in various ways, as owners of plantations or slave-ships, or involved in the sugar business, set about creating a strong campaign to oppose any limitations on their business. They argued that the brutality of slave-trading was highly exaggerated and that life on the plantations was better than Africans could expect in their native lands. Furthermore, if Britain gave up on slave-trading it would simply continue in the hands of other nations, particularly the French. The House of Commons agreed to undertake a parliamentary enquiry, which delayed any decision for a year.

James Ramsay, who had been a great aid to Wilberforce in gathering evidence about slavery, died in July of 1789 but the void was filled by two additions to the group, both of whom were known to Wilberforce as fellow students at Cambridge. Thomas Gisborne had been ordained and was a minister at a parish in Staffordshire, and Thomas Babbington a country squire in Leicestershire. They were both reunited with Wilberforce while delivering anti-slavery petitions to Westminster.

During this period a series of events took place that changed the mood in Parliament and were to set back the abolitionist campaign. The ruling classes in Britain watched with increasing horror as the French Revolution took place across the Channel. In 1791 abolitionist Thomas Paine published his book Rights of Man, arguing that people have rights that should be upheld by the government and monarchy. However, in the English colony of Dominica there was then a revolt by slaves who demanded certain rights of freedom. That was followed by a major rebellion by slaves in the French colony of Saint-Domingue where enslaved workers overthrew their masters and formed the independent nation of Haiti. Those who supported slavery argued that abolishing it would lead to the lower classes demanding rights in Britain, resulting eventually in the overthrow of the government and monarchy. Wilberforce was heavily defeated when, in April 1791, the issue of slavery was debated in Parliament.

Meanwhile, anticipating the eventual success of their campaign, the abolitionist group became involved in a major project. There were already many slaves who had been freed, particularly those who gained their freedom by fighting on the British side during the American War of Independence. A large number went to Nova Scotia or were living in poverty on the streets of London. An attempt, in which Granville Sharp was involved, was made to create a new colony in Sierra Leone in West Africa for over 400 from London but half died within the first year.

Wilberforce’s people became involved when in 1790 the black Nova Scotians appealed to be taken to Sierra Leone. The group decided to form a joint-stock company, the Sierra Leone Company, that would establish the settlement of Freetown. Their idea was to create a place in Africa that would be civilized with British values, legal, political and social systems, and Christianity. The colony would survive by growing sugar, and investors would profit in its trade. Thomas Clarkson’s brother John, a naval lieutenant, was sent to Nova Scotia to collect well over a thousand volunteers that he then carried across the Atlantic on fifteen ships. In England a large amount of money was raised from 500 subscribers for the venture, and a team of officials and craftsmen and women were gathered and sent out to set up Freetown. A land agreement was made with the local King of Koya, whose son was taught English and came to Clapham to stay at the house of Henry Thornton.

When John Clarkson arrived in Sierra Leone he discovered the officials and craftsmen from London had undertaken no preparations for the arrival of the settlers. There were continual disagreements and a series of setbacks. Former naval officer William Dawes, and Zachary Macaulay, were sent out to assist Clarkson. Macaulay had worked as a young man on a sugar plantation in Jamaica, which had turned him against the use of slave labour. By the time Clarkson returned to England to take a temporary leave he was bitter with the experience at Freetown and departed from the project.

Dawes set up a people’s parliament for the settlers of Freetown, with each household having a vote. There was no property qualification, and women who were the head of the household could vote, and thus it was far more democratic than in Britain. The black settlers, whose affiliations were divided between Methodist and Baptist, created seven churches. There were, however, major complaints against Dawes, who they believed had reneged on the promises that had persuaded them to leave Nova Scotia. They delivered a petition to the company in England to have him replaced by John Clarkson, but it was dismissed by Thornton and the other directors. The news of the refusal caused riots against the company in Freetown.

Dawes had already returned to England, leaving Macaulay as governor. In September 1794 Freetown was attacked by a flotilla of French warships and plundered. Despite their differences, the black settlers fed and sheltered Macaulay and the white company people. Yet the aftermath of the events created more friction between Macaulay and the settlers.

Zacharay Macaulay returned to England in 1798 where he became secretary of the Sierra Leone Company. In Freetown he had established a school and he brought 25 of the pupils with him to England to continue their education. The pupils stayed in Macaulay’s house at Clapham, to the amusement of his friends. The majority died of measles in 1805, however, and the survivors returned to Sierra Leone

Macaulay’s successor in Sierra Leone, Thomas Ludlam, inherited serious unresolved issues. In 1800 civil war erupted between several hundred settlers and those loyal to the company, resulting in the execution of two of the rebel leaders and the banishment of others. Ludlam resigned and was replaced by Dawes. The following year the exiled rebels returned together with forces of a local kingdom. The attack was repelled, but Dawes was injured and 18 Freetowners killed. By 1804 the financial reserves of the Sierra Leone Company were exhausted and the colony was only able to continue with an annual subsidy from the British government.

The parish rector of Clapham died in 1792 and was replaced at Holy Trinity by Henry Venn’s son John. Henry Thornton then purchased the house in which he had been living on Clapham Common, close to the church, and had it enlarged. Two more houses were built on the property, which were rented to Edward Eliot and Charles Grant and his family.

John Venn was very active in the parish. His sermons could attract up to a thousand people. He set up a school for children and their parents, the Clapham Poor Society to help the less well-off worshipers, founded a local militia in case of the expected invasion by Napoleon, and in 1800 saved the parish from a smallpox epidemic by arranging vaccinations.

Wilberforce brought his anti-slave trade Bill to Parliament in April 1792, supported by Henry Thornton, and William Pitt. The latter gave a speech that lasted from 4 o’clock in the morning until daybreak. MPs voted for a compromise, however, initiated by Home Secretary Henry Dundas by which the slave trade would be phased out over four years. When the Bill reached the House of Lords the Duke of Clarence, the future King William IV, led a call to delay any decision by holding a further enquiry. During the following year popular support for abolition waned and MPs threw out the idea of a gradual reduction in the slave trade. Two other Bills brought by Wilberforce – to prevent British ships supplying captives to colonies of foreign nations, and to limit the number of captives carried on British ships – were also defeated.

Meanwhile, the Lords dragged their heals on their abolition enquiry and it was finally discontinued in 1794. The Dundas Bill to phase out slavery was due to come into effect at the end 1795 if Parliament could still be persuaded, so in February of that year Wilberforce attempted once again to have anti-slave trade legislation passed. Yet he had lost favour with many of his parliamentary supporters, including Pitt, due to his opposition to the war with France and the Bill was heavily defeated. With the revolution in France still in full swing, Wilberforce supported measures by Pitt to curtail liberties in Britain, allowing the imprisonment without trial of anyone suspected of being a revolutionary. Wilberforce and Pitt were thus reconciled.

With his stance on anti-revolutionary measures, those in Parliament no longer viewed Wilberforce as the dangerous radical he once seemed. Sensing a change, in February 1796 he tried once again with an abolition motion. This time it was defeated by just four votes. A further defeat came in May 1797. In the 1798 parliamentary session he was defeated by 87 votes to 83, but the following year by a wider margin.

Ireland was a separate kingdom, under the British monarchy, with its own Parliament in Dublin. Irish nationalism, if allied to France, was a very real threat and could leave Britain surrounded by the French. Therefore in 1801 William Pitt incorporated Ireland into the United Kingdom, with Irish MPs thereafter sitting in Parliament at Westminster instead of Dublin. King George III refused to accept some of the promises made to Irish Catholics before the Union. Pitt resigned, to be replaced as Prime Minister by Henry Addington, who was opposed to abolition.

In 1802 John Shore, Baron Teignmouth, moved to Clapham with his family, joining Thornton, Wilberforce, Stephen, Macaulay, Venn, Eliott, and their families in the village. The circle launched their own monthly magazine, the Christian Observer, edited by Zacharay Macaulay with an editorial purpose of covering many topics from an evangelical point of view. It continued to be published until 1877, long after the deaths of its founders. The abolitionist group were also joined at Clapham by Spencer Perceval, another abolitionist and a future Prime Minister.

Various political and international events made Wilberforce delay any further attempts at an anti-slave trade Bill for several parliamentary sessions. Addington was forced to resign in May 1804 and Pitt returned as Prime Minister. Wilberforce brought his abolition Bill to the Commons for the tenth time. To everyone’s astonishment it was passed by an overwhelming majority, primarily because every Irish MP voted in favour. It also passed on its first reading in the Lords, but Pitt then killed the Bill because he believed members of the Upper Chamber would simply demand another enquiry. The abolition movement had been revived, however. Despite Pitt’s protestations Wilberforce brought forward the Bill again in February 1805. This time, however, the supporters of slavery were prepared and put forward arguments that won over uncommitted MPs. Once again, Wilberforce was defeated.

William Pitt died in January 1806. George III was forced to jointly appoint Charles James Fox and William, Baron Grenville as heads of the government and they assembled a cabinet who made abolition one of their priorities. There was still strong opposition in the Lords but James Stephen proposed a strategic move. Accordingly, the government introduced a Bill forbidding cultivation of new plantations in the colonies – something that even many plantation owners had already supported – and added to it an earlier attempt by Wilberforce on a ban of selling slaves to foreign colonies. The second part was meaningless in practical terms but ensured overall that the Bill was bound to succeed. The Foreign Slave Trade Abolition Act was passed and Fox introduced a parliamentary motion condemning the slave trade, which succeeded in both the Commons and Lords. A motion from Wilberforce that the King negotiate multilateral abolition with other slave powers passed without opposition, and a proposal from Stephen was passed preventing any new ships entering the trade.

Fox died in September 1806 and a new election was held, with abolition as a major issue. Stephen published his book New Reasons for Abolishing the Slave Trade, and Wilberforce wrote A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade…, which put forward his by then familiar arguments. Grenville arranged for the Bill to abolish the slave trade to go before the Lords in January 1807 where it passed by a large majority, and Charles (later Earl) Grey brought it for debate in the Commons.

On the second reading of the anti-slave trade Bill in the Commons Wilberforce shed tears as he was applauded by his fellow MPs. His question to Thornton was: “Well, Henry, what shall we abolish next?”. At the final reading Wilberforce declared that his next target was the total abolition of slavery. The Slave Trade Act came into law in March 1807, ending the slave trade on British ships and to British colonies. In the same year the Sierra Leone Company admitted defeat and petitioned Parliament to take over the colony.

The evangelical group centred around Clapham were far from alone in campaigning for the abolition of the slave trade but they certainly played a decisive role, not least Wilberforce’s tenacious and persistent pursuit in Parliament.

The abolitionists of Clapham felt compassion on the issue of slavery but as individuals they could otherwise be far from progressive. Their evangelical outlook made them self-righteous in the extreme. Throughout his career Wilberforce was quite conservative in his outlook. Many of the aims of the Proclamation Society, in which he took an active part, were repressive towards the lower classes. Wilberforce also supported Pitt in allowing those suspected of being against the state to be imprisoned without trial, and it was only late in life that he ceased to fiercely oppose Catholicism. When the Freetown settlers petitioned to have what they were originally promised, Thornton, Wilberforce and the other directors of the Sierra Leone Company quickly dismissed their demands. The former slaves could have freedom only on the terms decided by the abolitionists.

Opponent of abolition Sydney Smith had mocked the abolitionists as “the Clapham church” and “the patent Christians of Clapham”. In 1844 Sir James Stephen, son of the anti-slave trade campaigner, and by then Under-Secretary of State for the Colonies, wrote an article for the Edinburgh Review in which he mis-remembered Smith’s original description. Instead, he referred to his father and circle of associates throughout the article as “the Clapham sect”. The Review’s editor used Stephen’s misquote in the article’s title, and thus some years later the group mistakenly became known as the ‘Clapham Sect’.

The passing of the Slave Trade Act in 1807 largely ended the passage of captive workers on British ships but it did not end the use of slave labour in the British colonies, which continued for another 26 years. Wilberforce and Henry Thornton would campaign to completely abolish slavery, joined by a new generation at Clapham. Thornton died in 1815 and was buried at Clapham. William Wilberforce passed away in July 1833 and was buried in Westminster Abbey. Had he lived one month longer he would have witnessed the passing of the Slavery Abolition Act that ended slave labour throughout the British Empire.

< Back to England’s First Slave-Trading Company

Sources include:

- Stephen Tomkins ‘The Clapham Sect’

- James A. Rawley ‘London, Metropolis of the Slave Trade’

- James Walvin ‘A Short History of Slavery’

- Matthew Parker ‘Sugar Barons’