The development of Soho

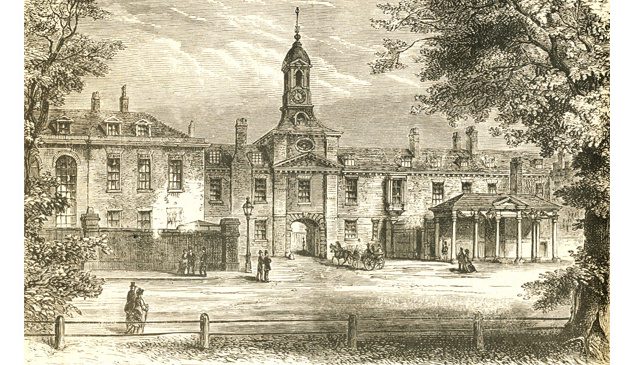

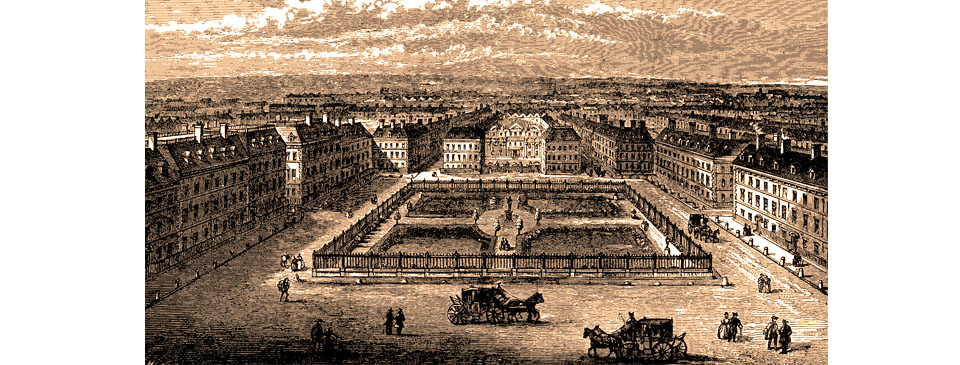

Soho Square in 1700 looking south. It was originally called King’s Square after Charles II whose statue stood in the centre. At the rear of the square in this illustration stands Monmouth House, a mansion completed in 1682 by Sir Christopher Wren for the Duke of Monmouth, the illegitimate son of Charles. He had little time to enjoy his house before he was arrested in 1684 and subsequently executed after staging an unsuccessful coup against his uncle, James II.

To the west of Leicester Square are Panton, Oxenden and Whitcomb Streets. Panton Street (as well as Panton Square, which has since been re-developed) was laid out by Colonel Thomas Panton who is reputed to have won a fortune gambling. Sir Henry Oxenden was yet another descendent – like John and James Baker – who had inherited land formerly owned by Robert Baker. Oxenden and Panton granted leases to the brewer William Whitcomb who laid out the street named after him.

When the Catholic James Pollett laid out Berwick Street in 1688-1689 he named it after his patron, the Duke of Berwick, illegitimate son of James II. John Sobieski, ruler of Poland who successfully ended the siege of Vienna by the Ottomans in 1683 was honoured in the name of Poland Street when it was laid out in 1689. By the 1690s the windmill that had stood at Windmill Field since 1560 (on what is now Ham Yard) had been demolished but continued to be remembered by the name Windmill Street (and later also by the Windmill Theatre).

In 1704 the Duke of Marlborough won a spectacular victory at Blenheim against the French army of Louis XIV and became a national hero. He was honoured in the name of Great Marlborough Street, which was laid out that year. In its first decades the street was noted for its magnificent buildings and gardens, inhabited by people at the highest social level.

As the population of Soho started to grow in the 1670s Henry Compton, Bishop of London began fundraising in order to build an Anglican parish church for the area. Money was slow to arrive and it was a further 10 years before St. Anne’s was consecrated, fronting on to what was then Princes Street but is now a continuation of Wardour Street. It is unclear who designed the church and it could have been either Sir Christopher Wren or William Talman. It took until 1718 for the spire to be added by the Soho carpenter John Meard (who is remembered in the charming Meard Street he laid out nearby), later replaced by the present tower.

In the first 50 years of its existence Soho – particularly Soho and Golden Squares – was largely populated by aristocrats and other members of the upper and middle classes. However a major difference to St. James’s (and, later, the various parts of Mayfair) was that there was no overall landowner to ensure a high quality of buildings and tenants. Almost from the beginning artisans, traders and immigrants moved into the many streets of Soho, creating workshops, and it became a mixed residential and commercial district. From the mid-18th century the area went into decline and the wealthier types of people who had lived in Soho, Golden and Leicester Squares in their early days moved on elsewhere, leaving them to people of a poorer sort. The buildings erected in Soho were built by a large number of different property speculators and builders, often of sub-standard workmanship and materials, and within a few decades were in poor condition.

Refugees, fleeing wars and persecution in Continental Europe began arriving in Soho almost from the beginning. The first were Greeks escaping the Ottoman invasion of their homeland in the 1670s. Led by their priest Joseph Georgirenes, they began building a chapel from 1677 in Hog Lane. It had barely been completed when the Greeks relinquished it amidst legal and financial wrangles over the ownership of the premises. It continues to be remembered in the name of Greek Street, which ran behind the chapel.

The next group of refugees were Huguenots from France who arrived in the district from 1681, most of whom were craftsmen. By 1692 they had taken over the former Greek chapel in Hog Lane (today’s Charing Cross Road) as well as founding the chapels Le Tabernacle in Milk Street (now Bourchier Street), another in Glasshouse Street, La Patente in Berwick Street and Le Quarre in a room at the rear of Monmouth House in Soho Square. Another was in Berwick Street and it gave its name to the adjoining streets, which were known as Little Chapel Street and Great Chapel Street. (Little Chapel Street was later renamed Sheraton Street). By 1711 the population of the parish of St. Anne’s, covering the Soho area, was slightly over 8,000, of which between a quarter and a half were French. The strong cosmopolitan nature of the area continued well into the 19th century.

Sources include: John Summerson ‘Georgian London’; Liza Picard ‘Restoration London’; Peter Whitfield ‘London: A Life in Maps; Lisa Jardine ‘On a Grander Scale’; Count Magalotti ‘Travels of Count Cosmo III Grand Duke of Tuscany’ (1669); Adrian Tinniswood ‘By Permission of Heaven’; ‘The Diary of Samuel Pepys’; Edward Walford ‘Old and New London’ (1897).

<Back to Late-Stuart London