The East India Company

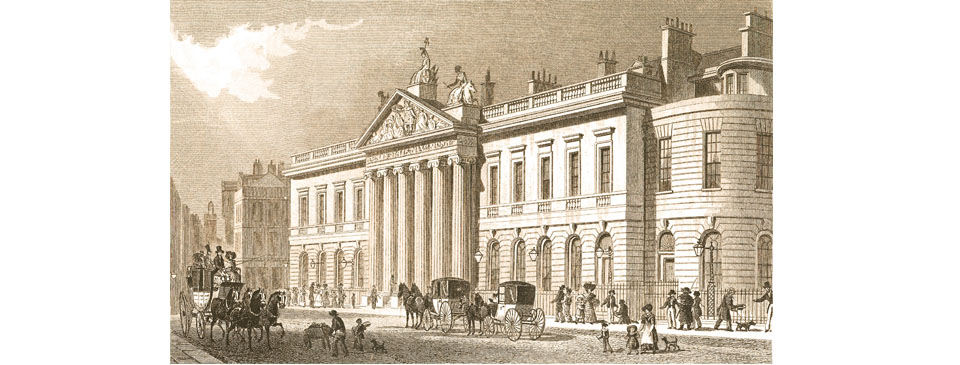

East India House in Leadenhall Street in the City of London. The Company had occupied the site since the mid-17th century but expanded several times. This building was designed by Henry Holland and work began in 1796. It included a museum housing the Company’s collection of exotic items. The building was demolished in 1862 following the Company’s demise and is now the site of the Lloyd’s insurance building. The drawing is by T.H. Shepherd and published in 1829.

One of the Company’s strengths was its sophisticated fleet, its handsome and heavily-armed East Indiamen equal or superior to ships of the Royal Navy, with gilded sterns and flying the Company’s striped flag. Initially the Company used ships owned by Levant Company merchants but from 1610 commissioned its own ships from a yard at Deptford, next to the Royal Dockyard. As business grew, vessels of up to 1,000 tons were required, larger than could be constructed at Deptford, so the Company took the decision to create their own yard. A marshy area slightly downriver on the opposite bank was chosen, by the fishing hamlet of Blackwall where Bow Creek flows into the Thames. Work began to create the yard in May 1614. It was operational within a few months, although not completely developed until 1619, by which time it was employing up to 400 workers. By then the Company operated a fleet of 10,000 tons, with 2,500 seamen. As with the royal dockyards on the opposite bank, the East India site at Blackwall was self-sufficient in all the needs of their ships, including the manufacture of its own ironwork and ropes. Employees were housed on site with their own victualing house where they could eat and drink. For security a large wall and water-filled ditch surrounded the premises. During the first forty years of the 17th century the Company built seventy-six ships.

For customs inspections, imported goods were required to be discharged at the Legal Quays in the City until the opening of the East India Docks in the early 19th century. The ships would moor at Blackwall and their cargoes unloaded onto barges to be taken upriver for inspection. From there the goods were moved to the Company warehouses in the City.

The Blackwall yard was a large fixed cost for the East India Company and when business became more difficult in the 1630s it proved to be a financial burden. After 1637 the Company ceased building its own ships and instead leased them from individual owners. The yard was sold in 1653 to a shipwright named Henry Johnson for considerably less than the Company had invested. Samuel Pepys’s recorded in his diary in January 1661:

…we took barge [from Greenwich] and went to blackwall and viewed the new dock and the new wett dock which is newly made there, and a brave new merchantman which is to be launched shortly, and they say to be called the Royall oake.”

The yard came back into Company hands in the early 19th century as the East India Docks.

After operating from the home of Sir Thomas Smythe the East India merchants moved to the nearby Crosby Hall at Bishopsgate until 1648. “The East India House is in Leadenhall-Street, an old, but spacious building; very convenient, though not beautiful” is how Daniel Defoe described the Company’s headquarters in the early 18th century, by then one of the landmarks of the City. In 1729 it was rebuilt to include warehouses and cellars and enlarged yet again at the end of the 18th century with a 200-metre neo-classical frontage decorated with statues. Its vast size included the Court Room hall, Finance and Home Committee Room, the Sale Room for auctions, and a museum and library. From East India House clerks known as ‘Writers’ wrote orders and other communications in longhand using quills and written in ‘Indian ink’, the replies to which would take a year to arrive back from the Far East.

The imports brought back to England were stored in the Company’s warehouses in various locations in the City. To cope with expanding business in textiles, tea, spices, ivory and other goods a new Bengal warehouse was opened at Bishopsgate in 1771, which by the end of the century had become part of the massive Cutler Street complex.

In 1756 the young and imprudent new Nawab of Bengal seized the East India base at Calcutta. The Company’s governor retreated, leaving a small number of British to defend their position, leading to the ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’ incident. The Company had from the start operated an armed security service to defend its ships and warehouses, which evolved into a private army. The following year this small but effective force defeated the Nawab’s much greater army at Plassey (Palashi), north of Calcutta. The victory was achieved in large part through bribery of the Nawab’s commanders, as well as deceit, undertaken by the Company’s Robert Clive.

The East India competed against a number of other European traders in Bengal, including the VOC and the French Compagnie Francaise des Indies Orientales. The conditions on which the ‘kulah poshan’ – or hat-wearers – could trade were imposed by the Indian rulers who ensured that business did not disrupt the fine balance of local commerce. Goods could only be purchased with silver bullion. The East India had ambitions to trade on its own terms, however, without the hindrance of competition, and England was anyway at war with France.

Having defeated the Nawab, the French and Dutch were largely expelled and Bengal systematically looted of its treasures, much of which were shipped back to England. A series of malleable puppet rulers was installed, each replaced according to the Company’s needs. To increase profits an internal and external monopoly was enforced, driving out competitors, directly buying from local manufacturers, and paying weavers the minimum possible for their labours. The Company also took control of local taxes, draining the province of its wealth.

At the end of the 18th century up to 90 percent of Bengal’s trade was in the hands of the East India Company. Within a decade it had reversed the direction of wealth, from India to England. Profits flowed back to shareholders, as well as the British government by way of annual payments. From its base in London, trading goods halfway around the globe, from the Orient to the eastern seaboard of North America, the East India Company was rapidly transformed into the world’s greatest business entity. Yet it did not have the internal structures to manage its distant staff or rule a large and highly-populated nation. Corruption was endemic. Clive and his fellow executives enriched themselves through private trading. Deprived of its social infrastructure, when Bengal suffered drought and famine in 1770 in excess of a million inhabitants perished while vast wealth continued to be transferred back to London.

The following year Warren Hastings was appointed as Governor of Bengal and during his tenure a much greater part of India was brought under Company control. His eventual recall and trial in Westminster Hall “in the name of the people of India, whose laws, rights and liberties, he has subverted, whose properties he has destroyed, whose country he has laid waste and desolate” was the most talked about event in London of 1788. The charges against Hastings took two days to read and the investigation and trial lasted seven years. The basis of the trial was two opposing views of the role of the governance of empire. Hastings was eventually acquitted.