The East India Company

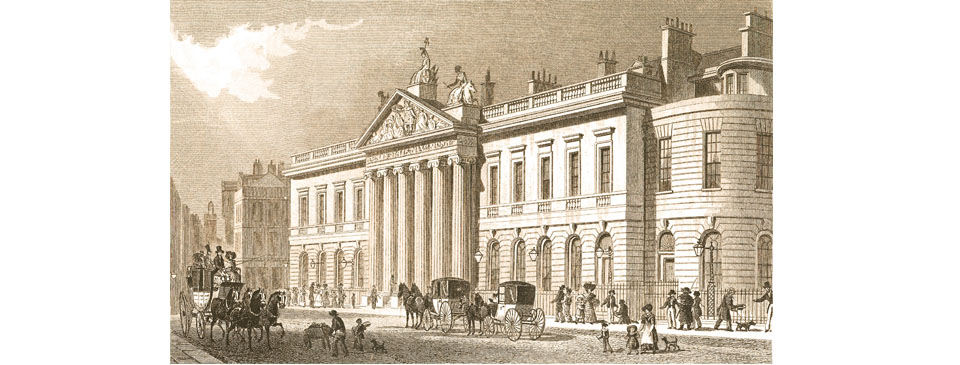

East India House in Leadenhall Street in the City of London. The Company had occupied the site since the mid-17th century but expanded several times. This building was designed by Henry Holland and work began in 1796. It included a museum housing the Company’s collection of exotic items. The building was demolished in 1862 following the Company’s demise and is now the site of the Lloyd’s insurance building. The drawing is by T.H. Shepherd and published in 1829.

In the second half of the 18th century there was a dramatic increase in the size of the East India Company’s army in India and by 1806 it employed over 150,000 soldiers, with mainly British officers and native conscripts. A separate navy had been developed around the coast of India to combat piracy. During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars three regiments of 1,500 Company workers were maintained for the defence of Company properties in the City of London. In 1809 a military seminary was opened near Croydon where cadets studied infantry, artillery engineering, surveying and languages.

Under Governor-General Richard Wellesley, and the army commanded by his brother Arthur (the later Duke of Wellington), more territory in India was brought under the Company’s control. In the seventy years until the mid-19th century the area of the Indian sub-continent ruled by the Company rose from just seven percent to 62 percent, which also included Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

By then the Company had for some years faced strong competition within its home market. Mechanisation in Lancashire’s cotton mills meant that by the end of the 18th century English-woven muslin was cheaper to produce than that imported from India. Whereas at the beginning of the Company’s rule India had been the world’s leading supplier of textiles, it became the largest importer of cotton goods from England due to lack of industrial progress. Opium, grown by the East India Company, was then its main export.

India was the only source of diamonds until their discovery in Brazil in 1725 and those imported by the East India Company led to London becoming a leading trader in the precious stones. In 1849 the East India Company won control of the Punjab and its defeated Sikh rulers were forced to surrender the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond to become part of Queen Victoria’s Crown Jewels.

A company trading post was established at Singapore in the early 19th century under the local governor, Stamford Raffles, as part of an Anglo-Dutch treaty. Raffles was especially interested in botany and zoology and became a founder of the London Zoological Society.

Tea, grown exclusively in China, overtook textiles as the East India’s most profitable commodity by the mid-18th century, doubling in volume every eighteen years. The beverage had first been brought to England by the Portuguese wife of Charles II. When mixed with slave-harvested sugar from the West Indies it transformed the drinking habits of people in Britain as an alternative to gin and was also popular in the colonies of North America. Especially large ships of 1,200 tons carried it to London, where quarterly auctions lasted up to six days, with over a million pounds in weight sold per day.

As they had in India, European merchants faced conditions under which they could trade in China. The Manchu emperor kept tight control and stipulated they must only make their purchases through local merchants at Canton on the Pearl River and pay in silver bullion. To evade the latter edict, the East India instead grew opium in India that could be used to pay for Chinese tea, silk and other exotic goods. Chinese styles caught the imagination of the British public, with porcelain and furniture made to order at workshops in Jingdezhan and Canton.

In the early 17th century a return voyage to the Far East would take about two years but by the end of the 18th century that had been reduced to an average of 114 days. In the days of sail, East India ships left Blackwall each January in order to be in time for the winds that were required to carry them across the Indian Ocean. Convoys gathered in mid-stream at Gravesend where live animals and victuals were taken on board for the journey and passengers and outbound Company staff and soldiers embarked. It was not unknown for ships to perish at the very first or last stage of their journey, grounded on the sands around the Kent coast. The worst such incident occurred in January 1809 when three East Indiamen heading for Madras were lost on the Goodwin Sands.

General ships’ crews tended to be recruited from amongst London’s poor but many died on the outward journey, so locals were often employed for the return. These were known as ‘lascars’, a word first used by the Portuguese to describe any Asian crew. Arriving in London in the autumn they had to survive the cold, often without lodgings, until embarking on an outbound ship early the following year. Amongst the earliest arrivals were “Saloman Cowrder of Poplar a niger sailor” who was married there in 1610, and Thomas Jeronimo who lived with his wife at Ratcliffe from 1616 and died on the East India ship Peppercorn en route to the Philippines. By the end of the 18th century lascars were a common sight on London’s streets.

After 1834 the East India no longer imported tea from China but continued to grow the opium in India that fed the trade. In the meantime they finally infiltrated the Chinese tea-producing areas to learn the secrets of its cultivation. Following the East India’s conquest of the Assam region of India, local varieties of the tea plant were discovered and Company created plantations there, the first harvest arriving in London in 1839.