The Fifty New Churches Act

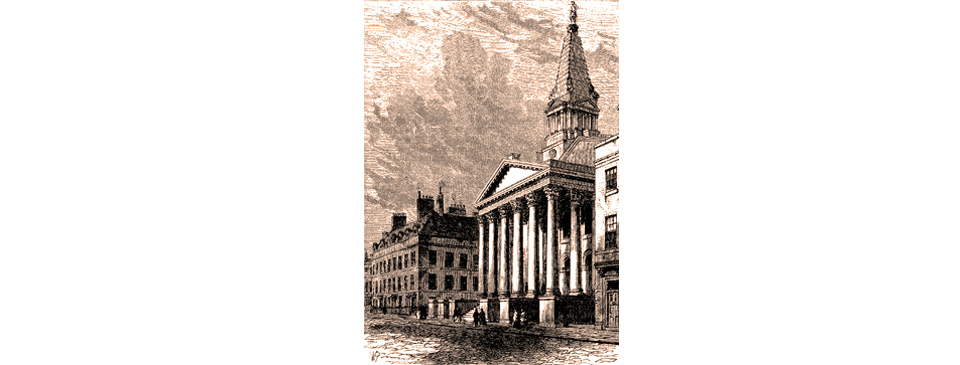

St. George’s, Bloomsbury was one of several of the ‘Fifty Churches’ designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor and was completed in 1731. Unusually, it features a statue of King George I atop the steeple. The church is probably best known for its depiction in William Hogarth’s engraving ‘Gin Lane’.

It was the view of the Commissioners that burials should no longer take place in churchyards surrounding London churches. For many years London’s tiny graveyards had been overflowing and become a scandal, with bodies buried on top of others and even being stolen and sold for medical research. Even before St. George’s was built the Fifty Churches fund was used to purchase a piece of land jointly with St. George the Martyr, Queen Square as a burial ground in open fields in the northern part of Bloomsbury. The hectare of land was divided by a wall, with one half for each of the two parishes. There was initially a reluctance to be buried so far from the churches and in an open field until an influential parishioner, Robert Nelson, was buried there and by 1725 there were around twenty burials each month. (The cemetery still remains as St. George’s Gardens to the north of Coram’s Fields).

The Scotsman James Gibbs designed St. Mary-le-Strand in 1714, which replaced an earlier building demolished in the 16th century. A Catholic, Gibbs had travelled to Rome in 1703 to become a priest but instead worked for the Italian architect Carlo Fontana, arriving in England in 1709. He was part of a social group of High Church Tories through whom – against the wishes of the Whig Vanbrugh – he gained his appointment as Surveyor. Reflecting Gibbs’s Italian tastes, St. Mary is the most Baroque of those built under the Act, notably its half-domed porch. The west end of the church was originally designed with a column topped with a statue of Queen Anne but she died before its completion and it was instead built with the present steeple, unusual in that it is broader on two sides than the others. The church was originally built with houses along its north side but they were demolished in 1910 and it now stands on an island in the Strand.

Commission member Thomas Archer was a pupil of John Vanbrugh and had studied Baroque architecture while travelling on the Continent. He built the church of St. John in the newly-created Smith Square at Westminster from 1713, in a similar style to that of Hawksmoor. Unfortunately, it was badly damaged in a fire in 1741 and the interior rebuilt with less grandeur. (It was also badly damaged during the Second World War and is now used as a concert hall). Archer’s other contribution to the ‘Fifty’ churches – St. Paul, Deptford (from 1713) – contains an impressive combination of semi-circular portico and steeple on a raised platform.

George, Elector of Hanover, succeeded Queen Anne in 1714. Like King William before him he was not an Anglican and was rather neutral towards the Church of England. He also detested the Tories because they had earlier betrayed him when, as an ally in the War of the Spanish Succession, they had secretly negotiated a peace treaty with the mutual enemy France. The Whigs therefore returned to dominance and remained in political power for several decades, marking the beginning of the end for the Anglican church-building programme.

In around 1715 a number of influential people were publishing works that criticised the English Baroque of Wren, Vanbrugh, Hawksmoor and Turner in favour of a return to the Palladian style that had immediately preceded them. The ‘Fifty’ churches were cited as examples of ‘foreign’, meaning ‘Catholic’. In 1716 the Fifty New Churches Commissioners were replaced by men who were fundamentally opposed to the scheme, viewed churches as necessities rather than monuments, and looked for ways to cut costs on those buildings under construction.

In 1715 there was an unsuccessful rebellion by Jacobites intent on deposing the new King George I in favour of ‘James III’. In the following year Gibbs was relieved of his post on account of his Catholic and Jacobite sympathies and replaced by John James. Although talented, James was not in the same league as Hawksmoor or Gibbs. His St. George, Hanover Square (from 1720) is an imposing building but lacking in the uniqueness that some of his contemporaries would have created.

Already by 1718 the Commission had committed to projects far greater than the revenue yielded by the tax. Enthusiasm for the whole enterprise waned, although both Hawksmoor and James retained their positions as Surveyors until the Commission ended in 1733. In 1727 they were requested to jointly design St. Luke, Old Street and St. John, Horsleydown in Bermondsey, on a budget at less than half the cost of the former work. Neither was of the same standard as the earlier churches and both were badly damaged in the Second World War.

In 1731 the decision was taken to rebuild St. Giles-in-the-Field, the parish church of the infamous rookeries (or slums) to the north of Covent Garden, paid from the Fifty Churches fund. The commission was given to Henry Flintcroft, a draughtsman and protégé of Lord Burlington. His design is reminiscent of Wren’s St. James’s, Piccadilly and Gibbs’s St. Martin’s-in-the Fields.

By the early 1730s the net result of the Fifty New Churches Act, paid from the continuing proceeds of the coal tax, was twelve new churches and the part-funding of others. Several Anglican communities were unsuccessful in their appeal for a new church. After 1730 the building of new churches in London slowed for several decades.

Sources include: Barry Coward ‘The Stuart Age’; Kerry Downes ‘Hawksmoor’; John Summerson ‘Georgian London’; Richard Tames ‘East End Past’; Gordon Barnes ‘Stepney Churches’. With thanks to Olwen Maynard for help with fact-checking, additional information and proof-reading.

< Back to Early Georgian London