The Great Fire of London

Wenceslaus Hollar’s contemporary illustration he named ‘The Prospect of this Citty, as it appeared from the opposite Southwarke side in the fire time’, which shows how the wind was spreading the conflagration from east to west. It was made from his imagination because he wrote after the event that it had “passed by us here at Whitehall. For all that there were great fears for one day that the flames would reach us here, I never saw them…”.

Throughout Tuesday the Duke of York and the King personally oversaw the work to halt the fire, riding up and down the lines of men encouraging them in their work pulling down buildings around Holborn. On occasions James even joined in to help pass buckets of water.

Despite all their efforts they were losing the battle and the fire broke through the stations at Coleman Street and Shoe Lane, destroying the church of St. Lawrence Jewry, the Guildhall and the surrounding buildings before moving on to the old city wall. The old medieval walls of the Guildhall were reported as glowing for hours in the heat of the blaze yet were robust enough that much of the building survived and could be rebuilt later. In the west the fire was fast approaching the Temple area to the south of Fleet Street where many of the resident lawyers were still away in the country for their long summer break. By then even the residents of Covent Garden, half a mile to the west, were beginning to evacuate. In the east, teams of men were demolishing buildings as fast as they could in an attempt to halt the fire, which was heading in the direction of the Tower against the direction of the wind. That evening it spread along the fashionable shops of Ludgate Hill to the old city gate itself. The inmates held in the prison on the upper storey of Newgate, deserted by their gaolers, broke free.

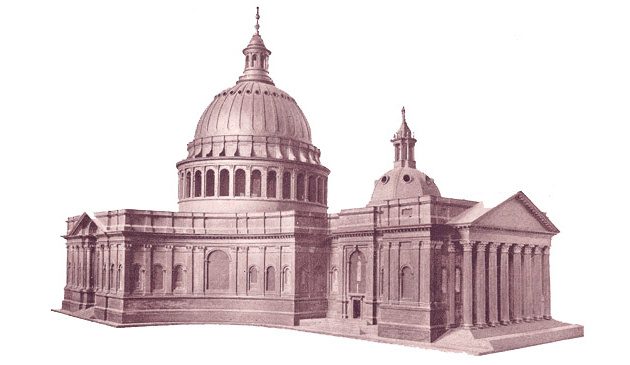

So far the fire had formed an arc around the south of the vast St. Paul’s Cathedral but it gradually crept towards it from the south and east. Although it raged in the surrounding streets there was no apparent danger to the building because it was constructed of thick stone and set in its own grounds away from other buildings. Booksellers, stationers and residents of nearby houses felt content in the knowledge that their possessions were safely stored in the crypt below. However, as with the steeple of St. Laurence Pountney and Salisbury Court, it was probably embers propelled by the wind landing on its roof that initially began to burn. At around eight o’clock on Tuesday evening the roof caught fire and within half an hour lead was melting and pouring down, running molten and glowing in a stream down Ludgate Hill. The stonework began to crack and when the combustible materials in the vault caught fire there was an almighty blaze, lighting up the entire sky at around nine o’clock, giving people enough light to read in the dark several miles away.

The fire crept ever nearer Whitehall Palace and the Duke of York and his men frantically demolished houses around the Temple and Somerset House. Plans began to be put in place to evacuate the palace, with Catherine of Braganza and the Duchess of York leaving for Hampton Court early on Wednesday morning. Panic set in as loud explosions, thought to be cannons being fired from the Tower, shook the entire city. In fact, it was military engineers using dynamite to urgently demolish buildings around the Tower in order to create a firebreak.

By Tuesday evening the Duke of York’s fire-fighters had been working continuously for two and a half days and were exhausted. At around eleven o’clock, however, the wind changed direction, blowing south, then overnight it began to die down altogether. The King had given up hope of saving his palace but ordered that every effort should be made to save Westminster Abbey. Yet the fire had only reached the church of St. Dunstan-in-the-West in Fleet Street. The Dean of Westminster arranged for scholars of Westminster School to take water buckets to save the church, however, and they managed to extinguish the flames when they were just three doors away.

Residents of the grand houses along the Strand were still evacuating by barges on the river but when it seemed there was some hope many ordinary residents of the western suburbs joined in the fire-fighting effort. The Duke pressed everyone he could find into service: men, women and children. Members of the King’s Privy Council rode up and down the line urging on workers and co-ordinating efforts.

Residents of the grand houses along the Strand were still evacuating by barges on the river but when it seemed there was some hope many ordinary residents of the western suburbs joined in the fire-fighting effort. The Duke pressed everyone he could find into service: men, women and children. Members of the King’s Privy Council rode up and down the line urging on workers and co-ordinating efforts.

In the east the fire reached All Hallows church on Wednesday morning but dockyard workers had been brought into action and buildings were being blown up along Tower Street, Mark Lane and Seething Lane. The church escaped with only minor damage. At around midday on Wednesday men under the command of the Earl of Craven finally extinguished the fire around Holborn Bridge and they rushed to help Sir Richard Browne’s men at the Cow Lane station. At Cripplegate the fire continued to rage but the Mayor finally began to order the destruction of houses there. Fires still burned throughout the City but by Wednesday evening the spread had been checked. The Duke ensured that each of the fire posts was still manned and operating and then went back to the palace to rest.

The vast devastation of the Fire was a combination of factors. It had been a hot, dry summer and the old wooden buildings were extremely flammable. From the beginning until the intervention of the King and the Duke of York there was a lack of leadership, in particular from the Mayor, Sir Thomas Bludworth, who could probably have halted the fire in its early stages by creating fire-breaks. People were more worried about saving their own possessions than tackling the blaze and perhaps there could have been a chance of holding it back with some co-ordinated action employing residents from other areas. Once the conflagration had taken hold in the south-east of the City it was the strong winds lasting for three continuous days that fanned the flames, moving it westwards. It was only when the wind died down overnight on Tuesday that there was finally some hope of containing the fire.

Sources include: Adrian Tinniswood ‘By Permission of Heaven’; John Richardson ‘Annals of London’; Liza Picard ‘Restoration London’; Stephen Coote ‘Samuel Pepys, A Life’; Lisa Jardine ‘On A Grander Scale’, Gillian Tindall ‘The Man Who Drew London’.