The Trial and Execution of King Charles I

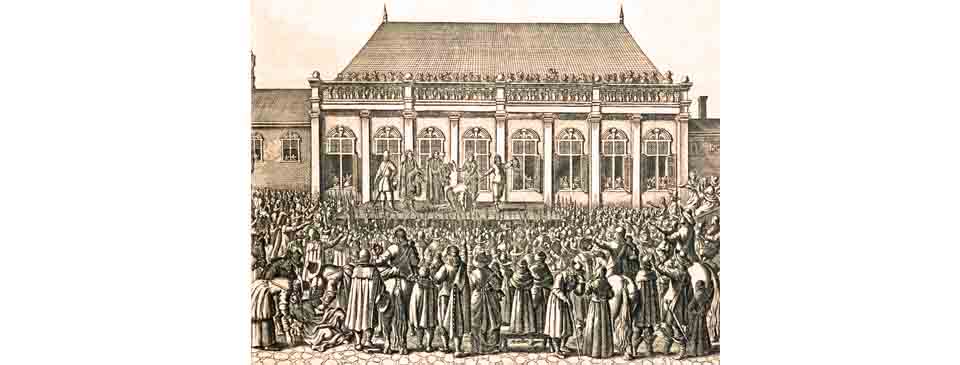

Pictures showing the execution of Charles I at Banqueting House were forbidden in England but soon began to appear on the Continent. The earliest engraving appeared several weeks after the event in the book ‘Theatrum Tragicum’, published in Amsterdam. A woman in the bottom left of the picture feints as the assistant executioner holds aloft the severed head of the King.

The actions of Charles I had divided political and religious opinion in the country leading to the Civil War that pitted King against Parliament. Charles was eventually defeated and held captive by the Parliamentarians, during which time his followers continued to rise up. After much debate, the King was brought to trial in January 1649.

The Civil War between King Charles I and Parliament lasted from 1642 until 1646 when the Parliamentary side were victorious. In May 1646 the King gave himself up to the Scottish army, hoping to agree a treaty that would eventually bring him back to power. The following January, however, the Scots handed him over to the English Parliament in return for a large ransom. Charles was initially held in Northamptonshire. By then a rift had occurred on the Parliamentary side. With the King held captive, Parliament had considered disbanding their New Model Army with only eight weeks of back-pay, far less than was in arrears. The army had also become highly politicised, with elements supporting views of the Levellers in London. Infuriated by Parliament’s decisions, some soldiers, led by the low-ranking officer Cornet George Joyce seized the King and took him to the army headquarters near Cambridge.

After further moves Charles was kept at Hampton Court Palace but in November 1647 he escaped to the Isle of Wight where the local gentry were staunchly royalist. There he was able to live as the king of the island, with a small court-in-exile, until the following February when the island’s governor complied with Parliamentary orders and moved him to house arrest in Carisbrooke Castle. From there the King attempted to negotiate with different factions in Parliament, as well as with the Scots. During the summer of 1648 there were Royalist uprisings in the south-east of England, known as the Second Civil War, but they were swiftly quashed by the New Model Army.

Despite years of Civil War many in the country still believed it possible to negotiate with the imprisoned Charles and that he could be returned to the throne. However, his escape from Hampton Court and his intended alliance with Scotland led others to doubt his sincerity in any settlement. The professional New Model Army was comprised of many anti-royalist radicals and republicans, led by Oliver Cromwell’s son-in-law Henry Ireton, who were no longer willing to support negotiations. At the suggestion of Cromwell a series of meetings was held between City of London radicals and leaders of the Levellers at the Nag’s Head tavern in London to agree a course of action and ensure unity with the army.

Following agreement at these meetings the army marched on Parliament at the beginning of December 1648 under the command of Thomas Pride. Radical leaders such as Henry Ireton and the preacher Hugh Peter called for them to “root up monarchy” by putting the King on trial, followed by his execution. The army prevented those MPs who believed in reconciliation from attending the House of Commons, the episode becoming known as ‘Pride’s Purge’. The remaining MPs, about 80 in number, were later to be known as the ‘Rump Parliament’ and they were ordered to put Charles on trial for treason. Oliver Cromwell initially argued in favour of continuing negotiations with the King but within a few weeks was persuaded that they would never succeed.

English monarchs had occasionally been deposed but never put on trial so Parliament decided to create an Act that established the High Court of Justice in order for it to take place. The trial took place in Westminster Hall. It was presided over by John Bradshaw, a militant London lawyer who had recently been appointed Chief Justice of Chester. Despite being of relatively minor repute he was appointed because more eminent professionals had refused to take part. Bradshaw was known as a detractor of the King, who had previously compared him with Emperor Nero. The Court was to consist of 150 commissioners including all the members of the House of Commons, six peers, some army officers, and aldermen of the City of London. Some refused to serve and the final number was reduced to 135. The commissioners convened on 8th January in the Painted Hall at Westminster to appoint officers of the court. Galleries and desks were set up in Westminster Hall for the trial.

The King was brought from Windsor and the trial began the following day on Saturday 20th January 1649, with 68 commissioners in attendance on the first day. Charles was brought by barge to Westminster Hall, cheered by people in boats who had come to watch.

Proceedings at the trial began with the reading of the Act setting up the court. The name of each commissioner was then called. One of their number was Lord Fairfax, the Parliamentary military commander against the royalist forces during the Civil War. When his name was called his wife shouted from the gallery: “Not here and never will be. He hath too much sense”. Fairfax had been one of those calling for Charles to be tried and punished and had attended the preliminary meetings of the commissioners. It is thought that he changed his mind when he realised the outcome would lead to the execution of the King.

Charles was then led into the hall and sat in an armchair that acted as the dock. Across his breast was the blue ribbon of the Order of the Garter, together with the Great George. In his hand was a cane topped with a silver knob and he wore a hat.

Bradshaw addressed the prisoner, that the Commons of England “being sensible of the evils and calamities that have been brought upon this nation and of the innocent blood that hath been shed in it, which is fixed upon you as the principal author of it…” had resolved to bring him to judgement and had set up the court for this purpose.

John Cook, the Solicitor General, lead the prosecution. But before he could begin Lady Anna de Lille, the Scottish widow of a French captain in the Royalist navy, cried out from the gallery that it was not the people who were putting the King on trial but “rebels and traitors”. She was seized by soldiers. The commissioner Colonel Hewson called for hot irons and branded her on the head and shoulder. Witnessing this act, Charles commiserated with her.

Bradshaw then asked the King to answer to the charge. He replied: “Let me know by what authority I am come hither and you shall hear more of me”. “Of the Commons of England,” stated Badshaw, “in the behalf of the People of England, by which people you are elected”. Charles retorted that for near a thousand years the kingdom had been hereditary and not elective and that he was entrusted with the liberties of the people. Charles refused to acknowledge the authority of the court, which Bradshaw then adjourned until the following Monday, perhaps hoping for a change in the King’s opinion. As Charles left, some onlookers cried “God bless him” and others “Justice! Justice!”.