Towards Civil War

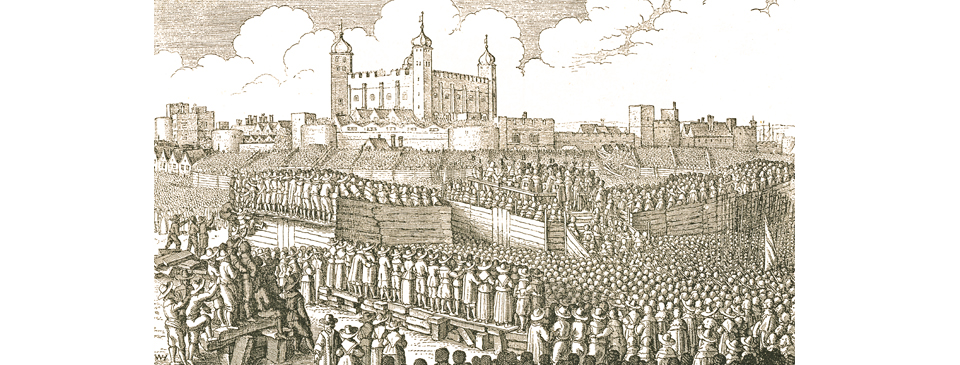

The execution of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford on Tower Hill in May 1641. His loyalty to the King made him unpopular with radicals. Parliament attempted to impeach him but failed due to lack of evidence of treason. However, Charles was under pressure from Parliament and therefore signed his death warrant despite his earlier reassurances that no harm would come to Strafford. The picture was drawn by the artist Wenceslaus Hollar who was a witness to the event.

It was the belief of King James I that the monarch ruled the country and that Parliament was merely a court for passing occasional laws. That led to conflict whenever Parliament obstructed his plans or would not approve his requests for funding. On occasions, when he failed to achieve his aims, and out of frustration, James dismissed Parliament and governed the country by personal rule. Another issue during his reign was the growth of non-conformist forms of religion, with an increasing portion of the population in England and Scotland turning their back on the established Church in England and Scotland. These issues increased in severity during the reign of his son, Charles I. It led the country into Civil War that lasted for over nine years, and Britain’s only period as a republic.

During the Middle Ages England was ruled by kings who raised finance through various forms of taxation to pay for the cost of the royal court and for an army and navy during times of conflict. However, from the 14th century Parliament took an increasing role in the setting and collection of revenue. Finance became a matter of negotiation between monarch and Parliament, with the latter demanding ever greater powers in return for funding. Queen Elizabeth, at the very end of her reign, circumvented Parliament by imposing taxes on goods being imported by London’s trading companies for which the Crown provided monopoly privileges.

The Scottish Parliament, which was independent of the English Parliament in Westminster until 1707, was more subservient to the Scottish monarchs. When King James VI of Scotland succeeded Queen Elizabeth, becoming James I of England, it was what he expected from the English Parliament. In that he was to be disappointed.

For several reasons, in contrast to his predecessor, James favoured an alliance with Spain, a country that was staunchly Catholic and opposed to Dutch Presbyterianism. The King’s policy initiated an early coalescence of Calvinist opposition forces that was to grow in the following decades and into the reign of his successor. That caused a reaction from James to suppress the Calvinists, with a resulting polarization between religious extremes. In 1621 the Commons passed a resolution demanding James go to war with Spain to protect the Protestants of the war-torn Palatinate, in what is now south-west Germany, but the King dissolved Parliament to avoid the issue.

King James died at Theobalds in Hertfordshire in 1625 and the succession of his son Charles was seen as a new beginning. Charles had absorbed much from his father, and inherited his views and tastes in politics, religion and the arts. However, the personality of Charles I contrasted with both his father and, later, his son in significant aspects. He suffered from a stutter and lacked communication skills, leaving many of his decisions unexplained and open to interpretation and misunderstanding. He was also stubborn, deficient in political sensibility, diplomacy and flexibility, often taking extreme positions without compromise. He presided over a very private and insular royal court that became increasingly detached from the realities of government and politics. In his youth he had learnt about Parliamentary business in the genteel House of Lords rather than the more cut-and-thrust House of Commons. The support for the anti-Calvinist Arminian view by Charles and his advisor, the Duke of Buckingham, and a botched military offensive against Spain, turned Parliament against Buckingham by the time it met in 1626. Parliament impeached Buckingham in 1626 and in response Charles dissolved Parliament.

The House of Commons of Parliament had become dominated by the land-owning class and monarchs found it troublesome to raise finance to pay for Crown activities through taxes on land. Charles could only legally raise new taxes with Parliament’s agreement and in 1626 it had unusually voted him rights on imports and exports for just one year. Therefore, when Charles dissolved Parliament he avoided an annual negotiation that would inevitably require concessions from him. Yet he then had to find new ways to raise finance and demanded loans from England’s wealthiest, many of whom were Calvinists so they refused to pay.

Following a disastrous assault against the French at Île de Ré in 1627 Charles was forced to recall Parliament for more funds. Yet there were great suspicions about his new French wife, Henrietta Maria, who had a private Catholic chapel at St. James’s Palace. The new staunchly-Protestant Parliament of 1628 would only agree to a continuation of taxes in return for anti-Catholic laws. The monarchy had long been receiving income by levying a duty on imports known as tonnage and poundage but MPs began protesting against any form of taxation not authorised by Parliament. Some of London’s merchants then refused to pay the duty. Again, in 1629 Charles dissolved Parliament. He had nine MPs arrested, including the prominent politician Sir John Eliot who died, and was buried, in the Tower of London. Parliament wasn’t recalled again for eleven years.

Religious opinion was becoming increasingly Puritanical, with a growing number having Calvinist views and wishing reform of the established Churches in England and Scotland. The overwhelming majority of religious activists in London – although not necessarily forming an overall majority of the people – were Puritans, what are referred to as Dissenters or non-conformists, of Presbyterian or Independent theology. Charles, on the other hand, believed in the High Anglican form of worship that was very ritualistic, which was not dissimilar to Catholic. With so much opposition from the Calvinists he increasingly turned to the Arminian clerics and Catholics for support. To the great dismay of Londoners, in 1628 he installed the clergyman William Laud as Bishop of London, a strong believer in the rule of bishops and ritualistic worship. In 1633 Charles elevated Laud to Archbishop of Canterbury, uniting the majority of Protestants against him. Charles and Laud planned religious reforms that seemed Catholic in all but name. Laud was succeeded as Bishop of London by William Juxon, who also became a close confident of the King.

Laud imposed a new policy on all parishes in November 1633. The communion table was to be moved from its normal position in the nave to the east end of each church such as it was in cathedrals, which angered even non-Puritans. This apparently small point was a visible sign to all congregations of the theological differences that separated most people from the Arminians and was one step too many in the direction of Catholic worship. The imposition of such uniformity, known as ‘Thorough’, created a great anger in the country, making Laud extremely unpopular, but he was able to carry out such measures because he had the backing of Charles. Thus, the King himself lost much support in the country.

In 1637 Laud had the ears of three men cut off for distributing leaflets attacking his policies, and Dissenters who failed to attend Anglican church services were fined. Lambert Osbaldeston, headmaster of Westminster School, fell foul of Laud, who ordered his dismissal and a punishment of being nailed to a pillory by his ears. Osbaldeston went into hiding before the punishment could be carried out, emerging three years later when it was safe to do so. During the following decade thousands of people sailed from London to the North American colonies, many to seek religious freedom.

Charles circumvented the tax problem in 1634 by broadening ‘Ship Money’ – the obligation for each coastal town to provide the Crown with either ships or money during times of war – to all towns in England and on a permanent basis. Charles used every lever available to him to extort funds from London’s merchants. The City magistrates tasked with collecting ship money found increasing resistance to making payment. Constant demands on the merchants of London to equip ships created much ill-will towards Charles, as did the forfeiture of lands in Ireland that the City’s livery companies had been forced to take by James I and on which they had spent large sums of money.

The relationship with the City was further tested when in 1636 Charles issued reforms of the complex rights and boundaries of London, against the wishes of the Lord Mayor and aldermen. It was a point that dated back to the beginning of the century but came to the fore again in the 1630s following several outbreaks of plague.