Towards Civil War

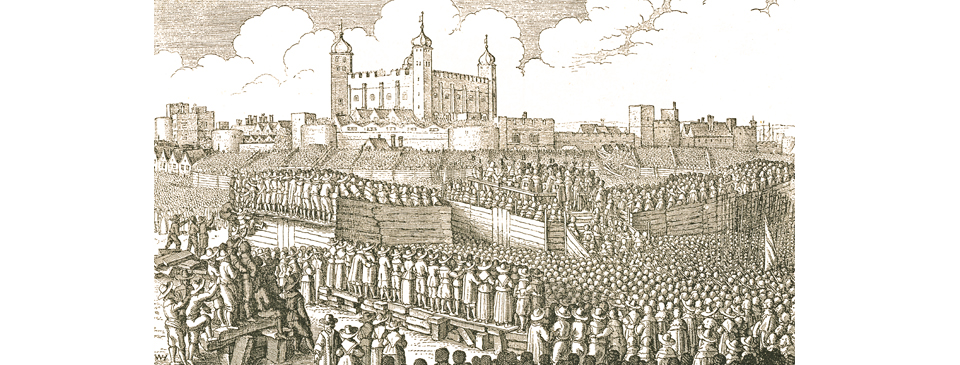

The execution of Thomas Wentworth, Earl of Strafford on Tower Hill in May 1641. His loyalty to the King made him unpopular with radicals. Parliament attempted to impeach him but failed due to lack of evidence of treason. However, Charles was under pressure from Parliament and therefore signed his death warrant despite his earlier reassurances that no harm would come to Strafford. The picture was drawn by the artist Wenceslaus Hollar who was a witness to the event.

Scotland had officially been Presbyterian since 1592 but in 1637 Laud instructed the Scottish Kirk to use the Anglican Book of Common Prayer. The Scots objected, initially sending a petition known as the Great Covenant. In 1638 the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland rebelled and replaced Scottish bishops with Presbyterian Elders. As Charles and Archbishop Laud attempted to prevent the rebellion a greater conflict broke out. The Scots raised the Covenanter Army, which marched on England in what became knowns as the ‘Bishops’ Wars’. Without a Parliament Charles was unable to raise new taxes to pay for an army to fight them, leading to a humiliating agreement in 1639 granting the Scots new religious freedoms.

The Scots began a process of further religious reforms and Charles was incensed by their insubordination. But he still needed money to raise an army to subdue them. In April 1639 the farmer of the customs, Sir Paul Pinder, raised £100,000. Most of the City’s 26 powerful aldermen remained loyal to the King but a large minority of the Common Council, which consisted of 237 London citizens, were opposed so Charles ensured that the Common Council were excluded from any considerations. Yet when in June the Crown demanded a loan of £100,000 from the City and £30,000 a month from the aldermen and wealthy citizens they refused. Sir Thomas Wentworth, Lord Deputy of Ireland, newly elevated to Earl of Strafford, was by then the King’s leading advisor. He recommended four of the defaulting aldermen be executed if Charles wished to control London but they were instead imprisoned. Charles also demanded money of London’s livery companies but they replied that their funds had been consumed by the confiscated Irish estates. A loan of £50,000 was given.

In March 1640 Strafford directed the Catholic Irish Parliament to provide subsidies to equip 9,000 men to fight against the Presbyterian Scots. Returning to England, Strafford then persuaded Charles to recall the Westminster Parliament, expecting the same response. It was therefore recalled in April for the first time in eleven years. Yet the King found little sympathy from MPs, with the leading oppositionist John Pym making a speech of an exhaustive list of grievances on a wide range of issues that had taken place since they last sat. The so-called Short Parliament was dissolved by the King in May after just three weeks without granting him his revenues. Instead, loyal members of the customs farming syndicate made a loan of £250,000. The East India Company, still loyal to Charles, made an agreement for the King to receive £50,000 through sales of pepper.

There was open hostility to Laud in London. A notice was posted at the Royal Exchange inciting apprentices to demolish his London home at Lambeth Palace. People congregated at St. George’s Fields but they were confronted by the Southwark trained bands. The apprentices tried again under cover of darkness but the Southwark militia were joined by those from Westminster and Surrey. As a precaution, Laud fled to Whitehall Palace under armed guard. The leaders of the riots were rounded up and executed for treason. There was minor disorder in London during the following week, but the four imprisoned aldermen were released.

The Scots moved south in August 1640 and occupied Newcastle without resistance, threatening further movement unless Charles recalled Parliament and agree to humiliating concessions. The occupation of Newcastle left London without its source of coal fuel. The ordinary people of London became increasingly important in shaping national affairs. Numerous citizens formed the radical elements of the City but names at the forefront were John Lilburne, William Walwyn and Richard Overton, as well as what became known as the Salters Hall Committee and overseas merchants such as Maurice Thomson and Thomas Stone. Importantly, these men had gained influence over the City Artillery Company, with its 500 members. In September Thomson delivered a ‘City Petition’ to the King, signed by 10,000 Londoners, demanding a new Parliament and an end to the war with the Scots.

Parliament was recalled again in November and was to sit for the following 20 years, becoming known as the Long Parliament. The City of London was represented by four MPs. For this new Parliament Matthew Craddock, Samuel Vassall, Isaac Pennington and Thomas Soane were elected. All four were Puritan overseas merchants who each had a long history of opposition to the Crown’s policies and Pennington, who was also an alderman, was to act as one of Parliament’s most militant members. The four acted as the conduit between Parliament and London, ensuring that Charles received only enough finance from the City as they deemed necessary.

The King was forced to agree a range of new legislation, yet as Parliament found time and time again, Charles had no personal commitment to Parliament and simply circumvented legislation he had approved. New laws included the Triennial Act whereby Parliament was henceforth required to sit on a regular basis in order to prevent a return to periods of ‘Personal Rule’ by the monarch. MPs also demanded the trials of the despised Laud, as well as Lord Strafford on charges of high treason, and both were sent to the Tower of London.

The ordinary people of London became increasingly important in shaping national affairs. Numerous citizens formed the radical elements of the City but names at the forefront were John Lilburne, William Walwyn and Richard Overton, as well as what became known as the Salters Hall Committee and overseas merchants such as Maurice Thomson and Thomas Stone. Importantly, these men had gained influence over the City Artillery Company, with its 500 members.

As soon as the new Parliamentary session began a petition was delivered, signed by over 15,000 Londoners, demanding “root and branch” reform of the Established Church. It was carried into Parliament by around 75 respected and wealthy citizens and presented by Pennington. Although no specific proposals were put forward, most Puritans favoured the ending of the episcopal hierarchy and bishoprics. There were still many moderate MPs, however, and their view was that laws should not be made simply according to petitions from radicals, so the matter went no further. In response many Londoners withheld money promised for Charles’s war against the Scots.

Strafford was accused of attempting to alter the constitution in favour of absolute monarchy. The initial impeachment against him that began in March 1641 failed but MPs were determined to bring him down. The House of Lords hesitated in their condemnation of Strafford but Londoners massed in the streets of Westminster to demand his execution. His eventual downfall came when a plot was discovered for the army to storm the Tower of London to free him. John Williams, Dean of Westminster Abbey acted as a mediator between King and Parliament and counselled Charles to sign Strafford’s death warrant. The Earl of Strafford’s execution took place on Tower Hill in May 1641 in front of a crowd of 200,000. People were reported as running from the scene, waving their hats and crying: “His head is off!”.

Scottish commissioners arrived in London to settle the disputes with the King and were welcomed by the town’s Puritans. Negotiations continued until the agreement of the Treaty of London in August 1641, with the Scots having achieved many of their demands.

In an attempt to keep control of London Charles bestowed honours on his supporters amongst the aldermen and returned the livery company estates at Londonderry. The King’s popularity in the City was also temporarily boosted by the election of the Royalist-supporting Lord Mayor Richard Gurney, holding office from November 1641. Charles visited Edinburgh in August to ratify the Treaty of London. On his return in November he was given a lavish and enthusiastic reception by supporters at a banquet in the City, organised by Gurney, who was awarded a knighthood.

There was a lengthy debate in the House of Commons during November regarding grievances felt by many of the opponents of the King. At the end of the month the Grand Remonstrance, a list of 204 grievances, was passed by a narrow vote and divided MPs into those for and against Charles. The Grand Remonstrance was presented to the King on 1st December. He delayed his response until the end of the month and due to the delay oppositionist MPs had it printed and distributed in London. When Charles finally responded at the end of the month he rejected it out of hand.

While the upper tier of London’s government, in the form of the Mayor and aldermen, remained loyal to the Crown, the City’s Common Council more accurately reflected the mood of the people of London, where there was an increasing resentment of the King and religious leaders. Many of Charles’s remaining supporters lost their seats in the December 1641 election for the Common Council, creating a divide in London’s government between that body and the Aldermanic Court. There was also division in Parliament, with the Commons pushing for various reforms but the Lords continually delaying and procrastinating.

At the end of the year there was actually growing support in Westminster for Charles and he was emboldened to act against his critics. In December 1641 he replaced the popular Sir William Balfour as Lieutenant at the Tower of London with the Royalist Sir Thomas Lunsford. But the following month close-cropped apprentices, known as ‘roundheads’, clashed with guards at Westminster and the Mayor of London informed the King that he could not be held accountable for peace in London if Charles did not remove Lunsford, to which the King agreed. To some extent that played into Charles’s hand and he was able to make pronouncements about how he was the defender of the State and Church against those who would turn the country upside down.

Charles received intelligence that five MPs were plotting with the Scots against him and that they also planned to indict his wife, Henrietta Maria, for promoting Catholicism. He headed for the Palace of Westminster on 4th January in a coach surrounded by redcoat soldiers to arrest them as well as Edward Montagu, Earl of Manchester, a member of the House of Lords. Parliament was fore-warned and the six men made a hasty escape by boat to London. At first they sheltered in St. Stephen, Coleman Street church, then went to the Guildhall. In the Commons Charles was confronted by the Speaker who, when asked where the MPs were hiding answered: “May it please your Majesty, I have neither eyes to see nor tongue to speak in this place but as the House is pleased to direct me, whose servant I am here.” Following that incident no reigning monarch has since entered the House of Commons, which is the origin of the tradition by which the door into the Commons is closed to the monarch’s representative prior to the State Opening of Parliament each year.

The following day Charles headed for the Guildhall in the City to demand that the Court of Common Council hand over the MPs but chaos ensued as opposing factions on the Council shouted their loyalty to King or Parliament.