Waltham Abbey

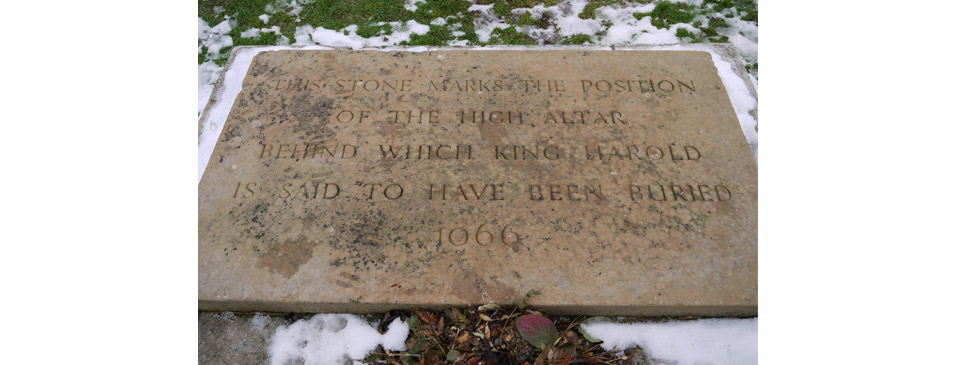

A stone slab that commemorates the burial of King Harold at Waltham Abbey in 1066. His tomb has never been found.

King Harold, who ascended the English throne upon the death of Edward the Confessor in January 1066, was famously killed at the Battle of Hastings just ten months later. Around a decade earlier he had founded a collegiate church at Waltham, close to the River Lea to the north of London. It was where his body was buried.

The events of Harold’s burial were recorded in 1177 in De Inventione Sancte Crusis Nostre (Concerning the discovery of the Holy Cross) by one of Waltham Abbey’s canons who had in turn learnt the details from the church’s older canons who had been there at the time. There were other theories regarding the whereabouts of Harold’s body but that author dismisses them as invented stories.

Harold’s body was initially buried at the battle-site. According to the medieval manuscript it was later recovered and, having been identified by his first wife, Edith Swan-neck, taken to his church at Waltham and re-buried with great ceremony. During the fifty-three years that the canon served there the church was rebuilt and he explains that the body was moved three times between 1124 and 1177. The exact place of the final burial is now unknown but a simple stone slab marks a potential spot, which now sits outside and behind the church.

The church of Waltham is one of the most ancient in the country. What is now the town of Waltham Abbey is known to have been a Roman settlement and it is possible there may have been some place of worship then, although no evidence survives.

The first church of which there can be any certainty probably dates from during the time of King Sabert in the early 7th century when Waltham was part of the kingdom of the East Saxons. A section of flint foundation in the present building dates from that time. There is further evidence in the form of an early 7th century clasp with Christian motifs, which would date the church from the time when Mellitus was Bishop of the East Saxons. However, the kingdom soon reverted to paganism and remained so for several decades. The original building is unlikely to have consisted of more than one or two rooms, probably built of wood on a foundation of flint stones.

Waltham became the minster church of a large area that stretched from Edmonton and Chingford in the south to Roydon in the north. It was enlarged or replaced, most likely during the reign of King Offa, around 790, when the East Saxons were dominated by the kingdom of Mercia. From 1016 England came under the rule of the Danish King Cnut and during that period the area was part of the estate of the king’s standard-bearer, Tovig.

Waltham became a place of pilgrimage during the medieval period, bringing prosperity to the town, due to its miraculous ‘Holy Cross’. The crucifix, made of black stone that ‘bled’ when jewellery was attached, arrived in around 1030 after being discovered at Tovig’s estate in Somerset. In fact, local stone in the area from which it originated exudes red iron when scratched.

The third church of the Saxon-Viking period was built according to the wishes of Harold Godwinson, Earl of Essex (later King Harold) during the 1050s as a secular college, or collegiate church. Following the arrival of the Normans, Waltham was rebuilt in the Romanesque style and some distinctive Norman arches still remain from that time. Work started in around 1090 at the east end and finished about 150 years later at the west where a pair of towers was erected.

As part of his penitence for the murder of Thomas Becket, Henry II re-founded Waltham church. At the time new religious orders were arriving in England from France and in 1177 it became an Augustinian priory. In 1184 its status was raised to an abbey and a Royal Peculiar, exempt from the control of a bishop. Waltham Abbey became the most important Augustinian house in England. A wealthy institution with royal patronage during the Middle Ages, it was often visited by monarchs on their hunting trips to Waltham Forest. During that period the abbey was greatly enlarged, with the addition of a cloister, chapter house, Lady chapel and living quarters for the canons. Two towers were added in about 1300, with one above the central crossing and the other replacing the previous twin west towers. By the completion it was comparable in size to a cathedral such as Durham, with the produce garden alone covering 18 acres and over one thousand acres of arable farm and meadows.

In 1536, during the Reformation, pilgrimages and other “superstitious practices” were abolished and the Holy Cross may have disappeared at that time. The abbey itself was largely destroyed four years later at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. The church had been a favourite of the king and it was the last abbey (but not last monastery) to be closed. The townspeople then claimed it as their parish church so about a quarter of the building was spared to remain more or less as it is today.

Sources include: the Waltham Abbey website; with additional information from Olwen Maynard.