Westminster Abbey in the Middle Ages

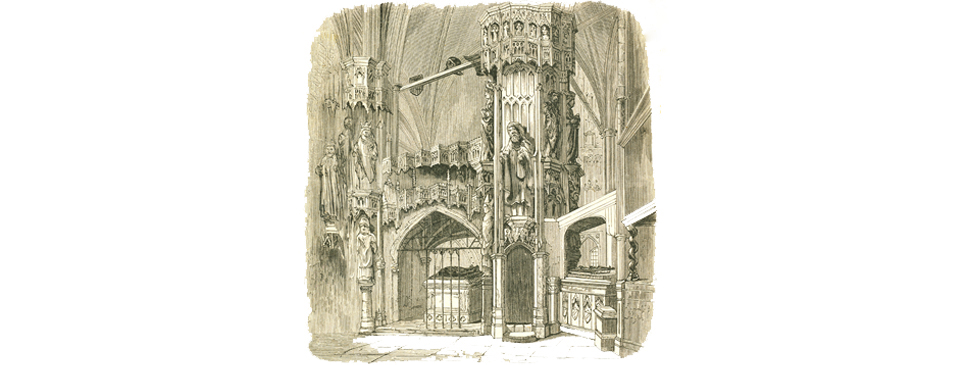

The magnificent chantry chapel of King Henry V. Henry died in 1422 and the chapel was completed in 1450, supervised by John Thirsk. Parts of the effigy were of silver but disappeared later in the 15th century. Other parts were stolen during the Reformation of the 1540s. The statuary depicts Henry as the king of both England and France.

It was Henry V who finally had the nave completed during his reign, although there was still then much work to be done to fulfil the wishes of Henry III of two centuries earlier. Henry also ordered the removal of the body of Richard II from its grave in Hertfordshire to be reburied at Westminster where he joined his wife Anne of Bohemia in a tomb that Richard previously had made for them, the abbey’s earliest double tomb. When Henry won the Battle of Agincourt in 1415 all London’s religious orders formed a procession from St. Paul’s Cathedral to Westminster Abbey, where the first recorded service of thanksgiving was held.

Henry’s military campaigns between 1415 and 1422 united northern and south-west France, including Paris, with England. It was while on the last of those campaigns that he died, and his body brought back to London. An obsequy was held at St. Paul’s before a cortège carried the body to Westminster. Within the abbey his lead coffin was carried along the nave on a chariot drawn by four horses, accompanied by white robed priests and, for the only time at a royal funeral, the royal standards of England and France. Edward the Confessor’s chapel, where earlier kings were buried, had become rather crowded so a mezzanine level was created for Henry’s tomb, creating a new chantry chapel. The shrine was regarded at the time as equal to that of a saint.

Henry’s widow, Katherine of Valois, remarried a Welshman named Owen Tudor and unwittingly founded a new royal dynasty. She was buried in the abbey’s Lady Chapel but her body exhumed in 1503 for work on a new chapel. Her remains were simply left on display. Over 150 years later Samuel Pepys recorded in his diary for 23rd February 1669:

…and her we did see…the body of Queen Katherine of Valois, and had her upper part of her body in my hands. And I did kiss her mouth, reflecting upon it that I did kiss a Queen, and that this was my birthday, 36 years old, that I did first kiss a Queen.

In 1778 her remains were re-buried in St. Nicholas’s Chapel and a century later Queen Victoria ordered them to be moved to Henry V’s chantry chapel.

Henry and Katherine’s son was only a baby when he ascended the throne as Henry VI and the coronation postponed until his eighth year. During the Wars of the Roses he would visit the abbey to pray and seek solace and to consider a place for his grave. He chose a spot and it was marked by a master mason but after his murder in the Tower of London in 1471 he was buried at Chertsey Abbey.

Edward V was born in the Abbots House at Westminster while his mother, Elizabeth Woodville, wife of Edward IV, was taking sanctuary from the forces who had deposed his father. On the death of Edward IV in 1483, 12-year old Edward was put in the care of his uncle Richard who escorted him to the Tower of London in preparation for the coronation. His mother was again at Westminster and ordered to dispatch her younger son, Richard, Duke of York, to join his brother at the Tower. The two boys were never seen again, and their uncle took the throne as Richard III. (Edward V is one of only two English monarchs to have never had a coronation in the abbey, the other being Edward VIII). Richard’s coronation was a solemn affair, with rumours in circulation regarding the disappearance of the two princes. In 1674 the bones of two boys were discovered under a staircase at the Tower. Charles II ordered them to be buried in the Lady Chapel at Westminster in a monument designed by Christopher Wren.

Westminster Abbey was a monastery of the Benedictine order and their monastic life had been laid down in Abbot Ware’s ‘Customary’ of about 1266. The ‘black monks’ observed a daily round of services. Between the services was a meeting in the Chapter house to read the Benedictine rule, participation in Conventional Mass, and masses for the dead. Manuscripts were read or copied in the north cloister and lives of saints written. It was a daily routine that only varied according to whether it was summer or winter. They slept in a common dormitory and ate together in the refectory. Baths were taken just four times a year, although they washed daily. The number of brethren varied over time but there were typically about forty priests and a further eight novices, headed by the abbot. They lived as a largely self-sufficient community, with about 100 servants. The abbey’s almonry housed the Song School from at least 1341, which eventually evolved to become Westminster School.

The abbey was adjacent to the royal palace so there were many visits from distinguished visitors. Parliament met in the abbey’s chapter house and refectory. There were visitors from other monasteries and likewise those of Westminster travelled to other religious houses. Visits could be made to study at Oxford. The community were not immune to the temptations of secular life, however. In the 15th century the brethren were known to frequent a local brothel known as the Maydenshed.

Since the 10th century the abbey had held a large amount of the land to the west of London which provided an income to cover its costs. Other manors were acquired at Hendon, Hampstead, Wandsworth and Belsize. Additional small plots were acquired in the 11th and 12th centuries. There were also royal and aristocratic legacies.

Westminster’s abbots were political grandees. They typically lived in one or more of the manor houses held by the abbey and only dined with the brethren on special occasions. Two successive abbots abused their position. Abbot Kirton was investigated by papal mandate on charges of being a fornicator, a dilapidator, an adulterer, and a simoniac, the latter being the seller of pardons. He was suspended from his post and replaced by George Norwych. He, however, led an extravagant life, accumulating very large debts for the abbey. The monks petitioned Henry VI and Norwych retired.

For centuries monks had produced manuscripts that had to be hand-written or copied but that was to change. In the early 16th century the works of Martin Luther were being printed and distributed across Europe. In 1476 William Caxton returned to England from Cologne and Bruges where he had learnt about printing. He rented a house close to the abbey’s Lady Chapel and there set up England’s first printing press. He remained at Westminster until his death in around 1492 and during that time translated and printed around a hundred books, including Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Caxton was also an active parishioner at the abbey and often audited the church accounts. He died in around 1491 and was buried at St. Margaret’s church at Westminster.

Sources include: John Field ‘Kingdom Power & Glory’; Richard Jenkyns ‘Westminster Abbey’; Edward Walford ‘Old and New London’ (1897); Thomas Cussans ‘Kings and Queens of the British Isles’.